Early Power Generation

In 1831, Michael Faraday devised a machine that generated electricity from rotary motion, but it took almost 50 years for the technology to reach a commercially viable stage. In 1878, in the US, Thomas Edison developed and sold a commercially viable replacement for gas lighting and heating using locally generated and distributed direct current electricity.The Edison plant supplied its light through incandescent lamps. In 1882, a similar kind of lighting, in an improved form, was proposed for Los Angeles by Charles L. Howland, initially representing a San Francisco based company, the California Electric Light Company (now PG&E). Howland would within a year incorporate with other investors and form his own company, Los Angeles Electric Company. This would become LA's first electric utility. |

|

|

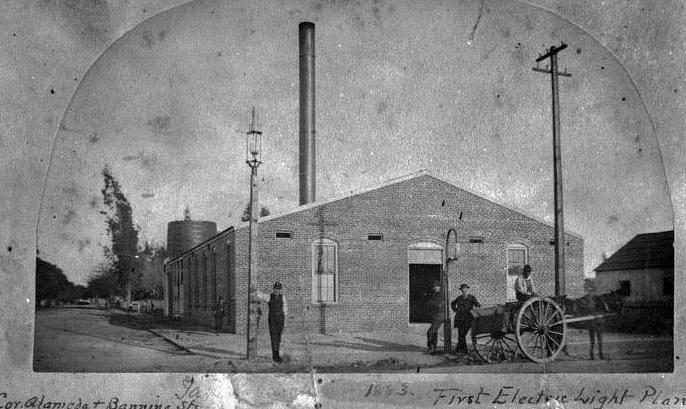

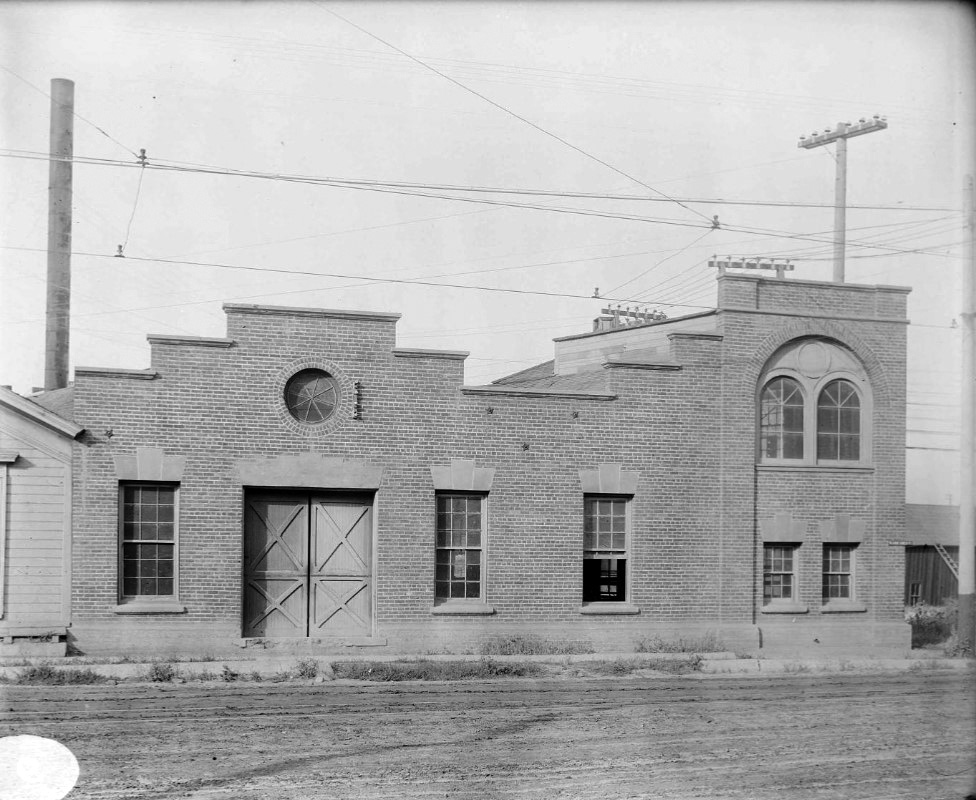

| (1883)* - Banning Street Electrical Plant -- The first electric light plant in Los Angeles was built in 1882 by Charles L. Howland on the corner of Alameda and Banning Streets (In 1883, Howland and others formed the Los Angeles Electric Company). |

On September 11, 1882 the Los Angeles City Council unanimously voted to enter into a contract with Howland to “illuminate the streets of the city with electric light.” The contract called for Howland, at his own expense, to install seven 150-foot-high masts each carrying three electric lamps and to provide the distribution poles, lines, and the electrical energy needed to light them. Howland set quickly to work. He had received a deadline of December 1, 1882 to have the masts erected and electricity on. By October 25, he had purchased a lot on the corner of Alameda and Banning Streets where he proceeded to put up a brick building, 50 by 80 feet, to house the boilers, engines and the 30kw, 9.6 ampere “Brush” arc lighting equipment for supplying the electric energy. Three weeks later, by November 16, the masts were in place and soon afterwards the pole lines and wires were strung along the streets leading to the masts. The project was considered so successful that before the expiration of Holland’s two year contract, he and others had formed the Los Angeles Electric Company, which besides serving streetlights, supplied arc lights for commercial establishments. That company would later evolve into the LA Gas and Electric Corporation. |

Historical Notes It should be noted that in addition to providing power for electric street lights, the early power plants mainly provided electricity for the new electric railways that were proliferating throughout the Southland. Charles H. Howland also chartered the first electric streetcar company in Los Angeles, LA Electric Railroad Company, on September 11, 1886. It began operations on January 4, 1887 with the line opening from Pico Boulevard and Main Street traveling west to Harvard Boulevard. In 1896, many of the major horse and cable cars operating in Los Angeles converted to electrical power.**^ |

Click HERE to see more of LA's First Electric Streetlights |

|

|

| (n.d.)* - Map showing location of Howland's new Electric Plant, corner of Alameda and Banning streets. Also shown is the LA Plaza. |

|

|

| (1888)* - Banning Street Electrical Plant now showing two smokestacks. It appears that the building as been enlarged from its original footprint as seen in the previous 1883 photo. |

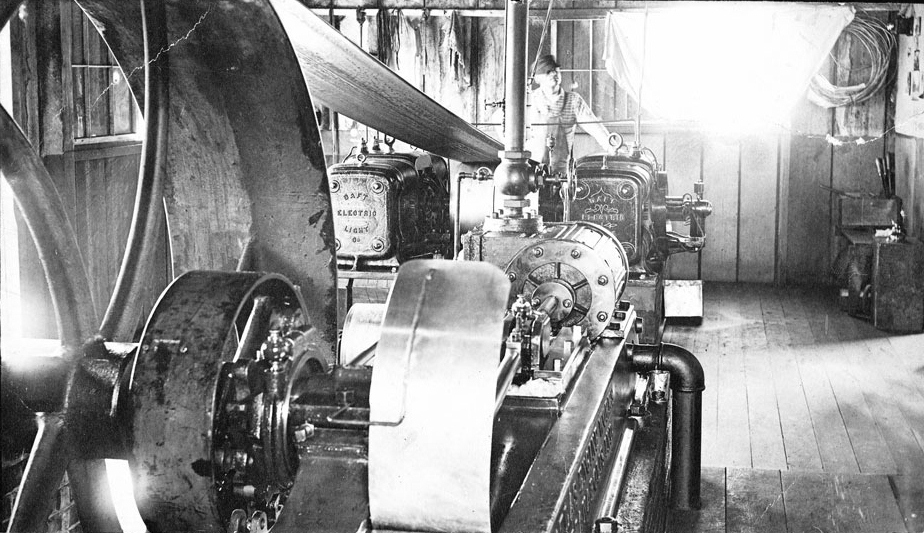

Early Electric Light Generators (ca. 1895)

|

|

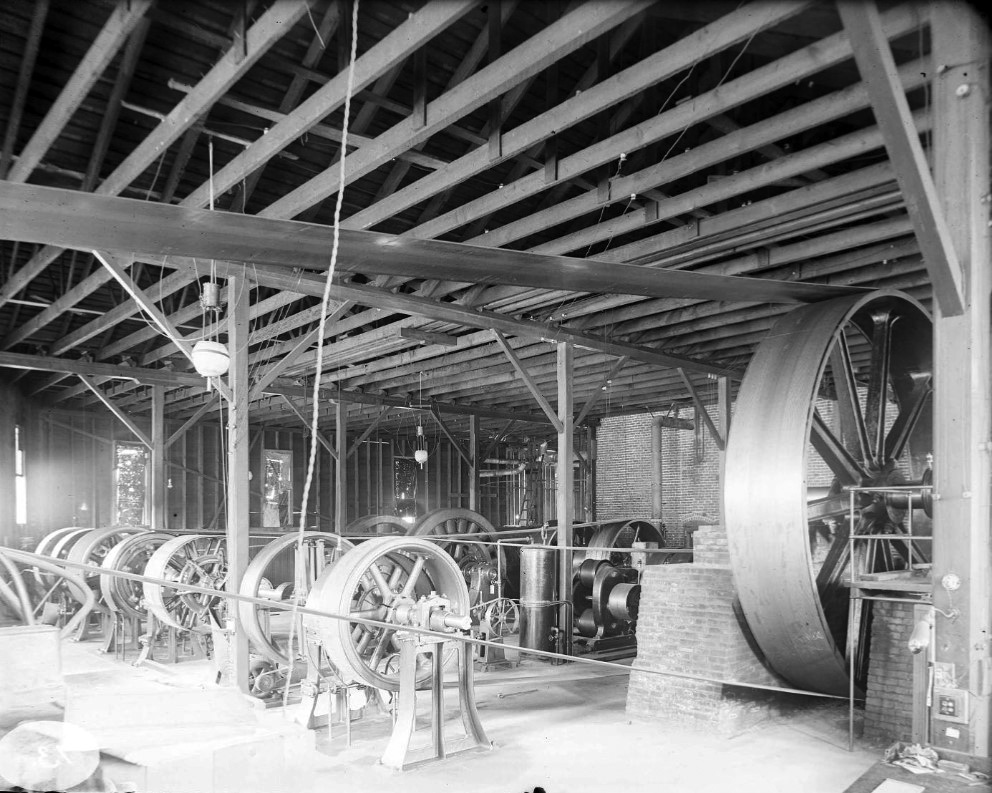

| (ca. 1895)^* - Photograph of a man operating electric light generators in Los Angeles, ca.1895. The generators are at center and are belt-driven by reciprocal steam engines. The belt can be seen at center and is connected to a gigantic metal wheel in the foreground at left. A man is standing in the background near the electric generators. The room in which the generators are housed has wooden floorboards and wooden walls. The electric generators have the words "DAFT ELECTRIC LIGHT” engraved on them. |

* * * * * |

Early Electric Power Plants

West Side Lighting Company Steam Plant (1896)

|

|

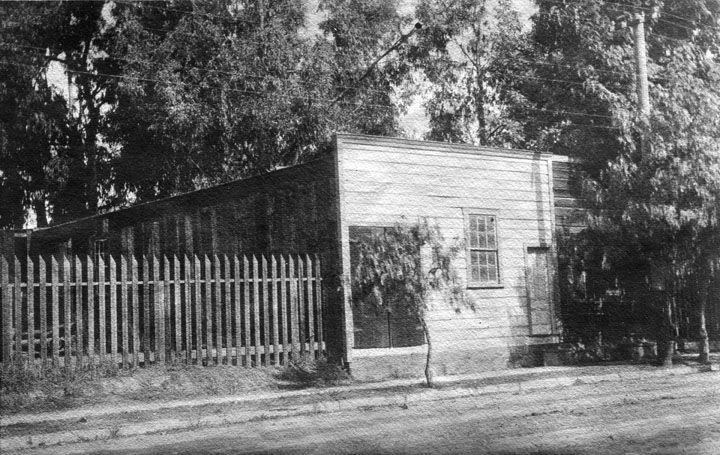

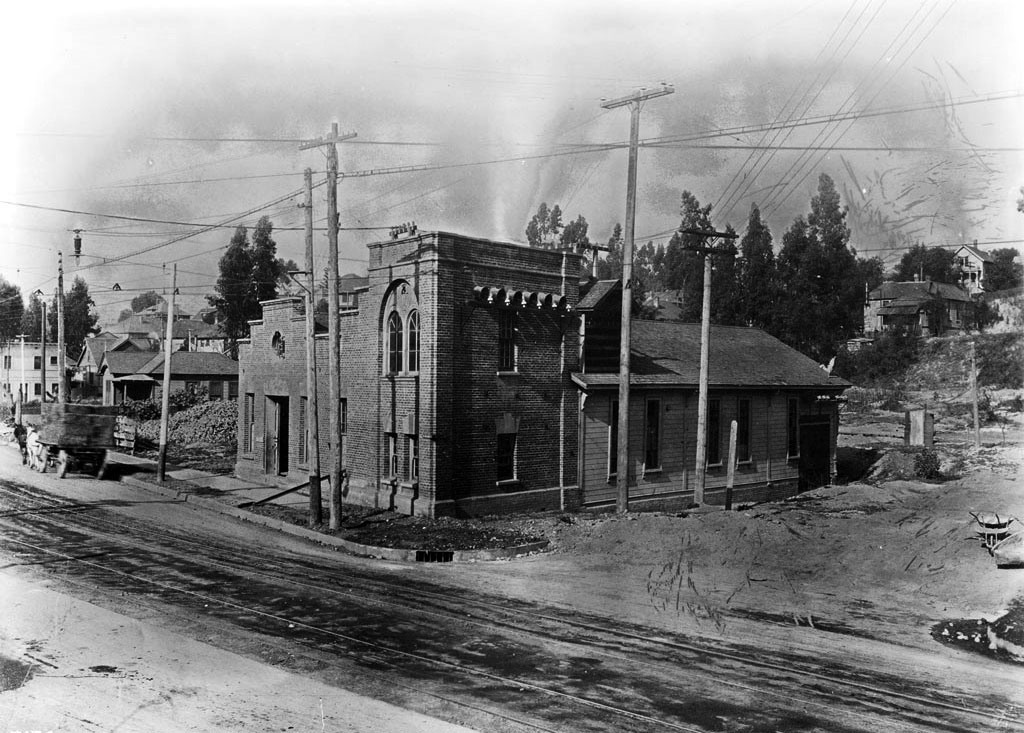

| (ca. 1887)*– View showing the West Side Lighting Steam Plant, established in 1896 on Vermont Avenue near 22nd Street (West Side's first power plant). |

Historical Notes In 1896, West Side Lighting Company was organized by private investors to provide another source of electricity for the city of Los Angeles and fringe areas. Their first large Power Plant was built on the northwest corner of 2nd and Boylsten streets. |

|

|

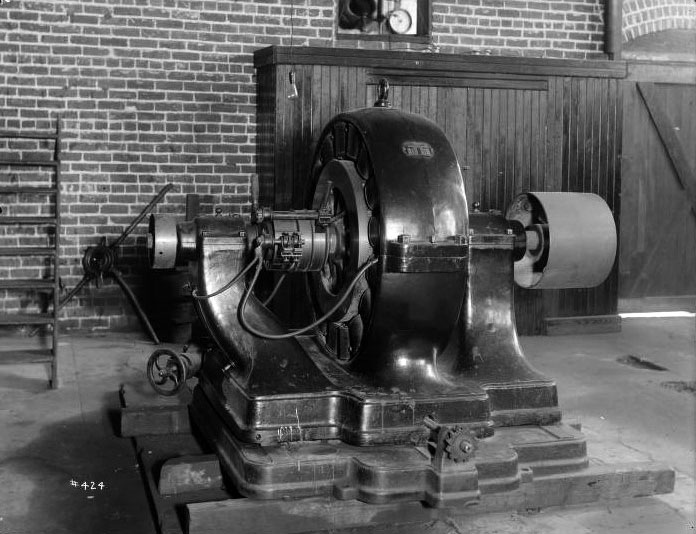

| (1910)* - The old arc machine (power generator) which was originally at the West Side Lighting Steam Plant on Vermont and 22nd Street, but the picture was probably taken in Los Angeles No. 1 Steam Plant. |

* * * * * |

LA Steam Plant No. 1 - LA Improvement Co. (1885); West Side Lighting (1896) - LA Edison Electric (1897)

|

|

| (1896)* – View looking south on Boylston Street toward 2nd Street, where the Los Angeles No. 1, Boylston Steam Plant is seen on the northwest corner. The power plant was originally built in 1885 for the 2nd Street Cable line. In 1896, the plant was purchased and expanded by the West Side Lighting Company and is seen above. |

Historical Notes One of the first power plants in Los Angeles, located on the northwest corner of 2nd and Boylston streets, has a rich history. Built in 1885 by the Los Angeles Improvement Company, the plant initially served the Second Street Cable Railway. However, after the railway ceased operations a few years later, the plant sat idle until 1896. That year, the West Side Lighting Company, organized by private investors to provide additional electricity to the city and surrounding areas, purchased the plant. They scrapped the cable winding machinery and installed generators. In 1897, West Side Lighting merged with the newly established Los Angeles Edison Electric, adopting the Edison name and patents, especially the underground DC-power rights. The merged company took on the Edison name. An underground system and technology were crucial at that time, as the city had passed a resolution limiting the installation of new overhead utility poles due to excessive wire congestion. Los Angeles Edison Electric installed the first major DC-power underground conduits system in the Southwest. By 1939, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) had become the sole power service provider for the city. Today, LADWP maintains a facility at this historic site. |

|

|

| (ca. 1900)* - View of Second Street looking east toward Boylston Street showing the Edison Electric Company Steam Plant No. 1. A man with a horse-drawn tanker wagon is making his way away from the camera along the unpaved road, with the Edison Electric power house behind a picket fence to his left. |

Historical Notes Between 1897 and 1906 the power house was in use as Edison Electric Company Steam Plant No. 1. This was Edison's first power plant located in the City of Los Angeles. |

|

|

| (ca. 1902)* - An interior view of the Edison Steam Plant No. 1 as it appeared before its conversion to a substation. |

|

|

| (ca. 1902)* - View showing the switchboard at Edison Steam Plant No. 1. |

|

|

| (ca. 1902)* – View looking across an unpaved 2nd Street at Boylston Street showing the front of Los Angeles No. 1 Steam Plant. |

|

|

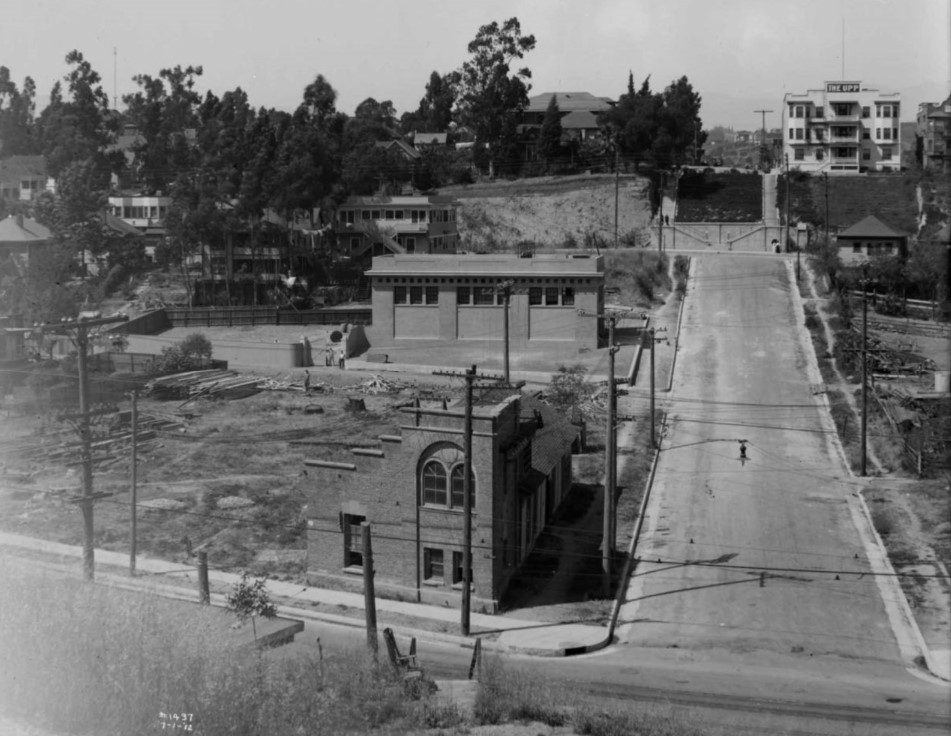

| (ca. 1906)* - View showing the 'old' Edison Electric Steam Plan No. 1 located on the northwest corner of 2nd and Boylston streets. The auxiliary buildings with clapboard veneers and smokestacks that once were attached to the corner brick building have been removed.The two-story brick utility building now stands next to a cleared lot in front of an unpaved road in which streetcar rails can be seen, surrounded by utility poles. |

Historical Notes At the time of this photo the brick building at the corner of 2nd and Boylston streets, once part of Edison Electric Steam Plant No. 1, was no longer being used as a power plant. It now was serving as an Edison Electrical Sub-Station. In 1909, Los Angeles Edsion Electric changed its name to Southern California Edison (SCE). |

|

|

| (1912)* – View looking north on Boylston Street from above 2nd Street. The 'old' Edison Steam Plant No. 1, later converted to a Sub-Station, is on the N/W corner. A newer, more modern Sub-Station stands a couple hundred feet behind the old one at center of photo. The hill in the background is filled with apartment buildings and homes. Today this same hill is occupied by Belmont High School. |

Historical Notes Over the years the Boylston facility has been used by the West Side Lighting Company, Los Angeles Edison Electric, Southern California Edison, and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which has occupied the site since 1940. Click HERE to see more in Early Boylston Street Yard. |

* * * * * |

Pacific Light and Power Company Power Plant (ca. 1912)

|

|

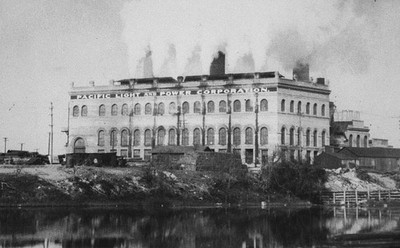

| (ca. 1912)^ - View showing the Pacific Light and Power Company power plant. It was built in 1902 to provide electricity for the Pacific Electric Red Car system in Los Angeles and the surrounding Redondo Beach area. |

Historical Notes This was Pacific Light and Power Company's first power plant. SCE would purchase Pacific Light and Power in 1917. In 1946 SCE constructed a new power plant at the same site. Today, a modified version of this new plant is owned and operated by AES.* |

|

|

| (ca. 1920s)* - View of the Redondo Beach Pacific Power and Light Plant after it was purchased by SCE. |

* * * * * |

Early LADWP Power Plants

In 1909 the Bureau of Los Angeles Aqueduct Power was created to build hydroelectric power plants along the Los Angeles Aqueduct. When Los Angeles acquired water rights in the Owens Valley section of Inyo County to construct the LA Aqueduct, it also obtained water-power sites along the way. Ezra F. Scattergood was selected as the Bureau’s first chief electrical engineer. Scattergood led the way in the development of hydroelectric power along the route of the aqueduct and became Mulholland’s counterpart for the Power System. |

San Francisquito Power Plant No. 1 (1917)

|

|

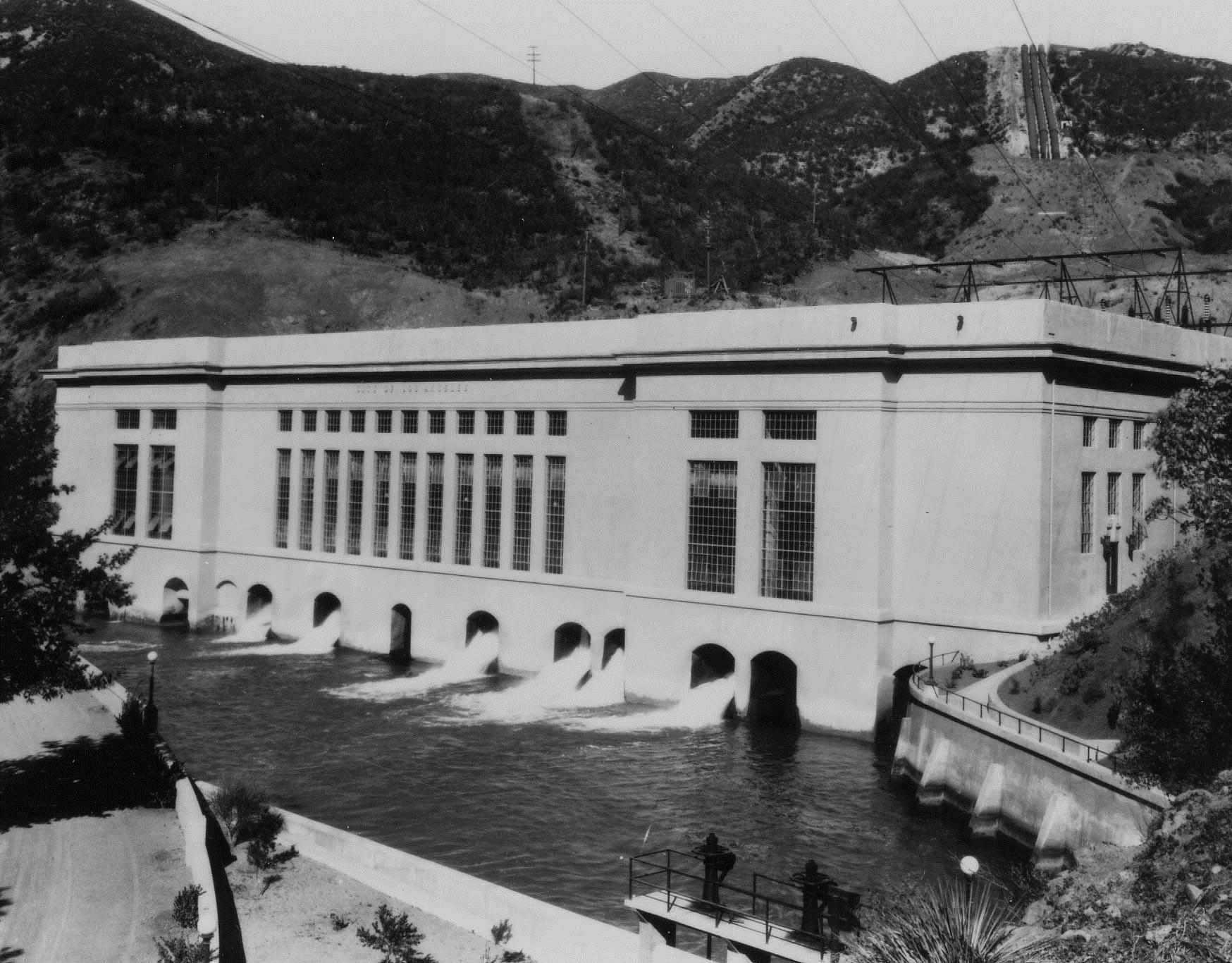

| (1917)* - View of the San Francisquito Power Plant No. 1 just before its opening. Construction of this power plant was the Los Angeles Bureau of Power and Light's first step in becoming an independent electricity provider. |

Historical Notes Construction of he San Francisquito Power Plant No. 1 began in 1911 at the same time the LA Aqueduct was being built (1907-1913).* |

|

|

| (n.d.)* - Interior view of Power Plant No. 1 showing the turbine-generators. |

Historical Notes To drive the turbine-generators, water from the Aqueduct falls 940 feet down the steep side of San Francisquito Canyon, and plays on the water wheel that turns the generator through 14-inch nozzles.* |

|

|

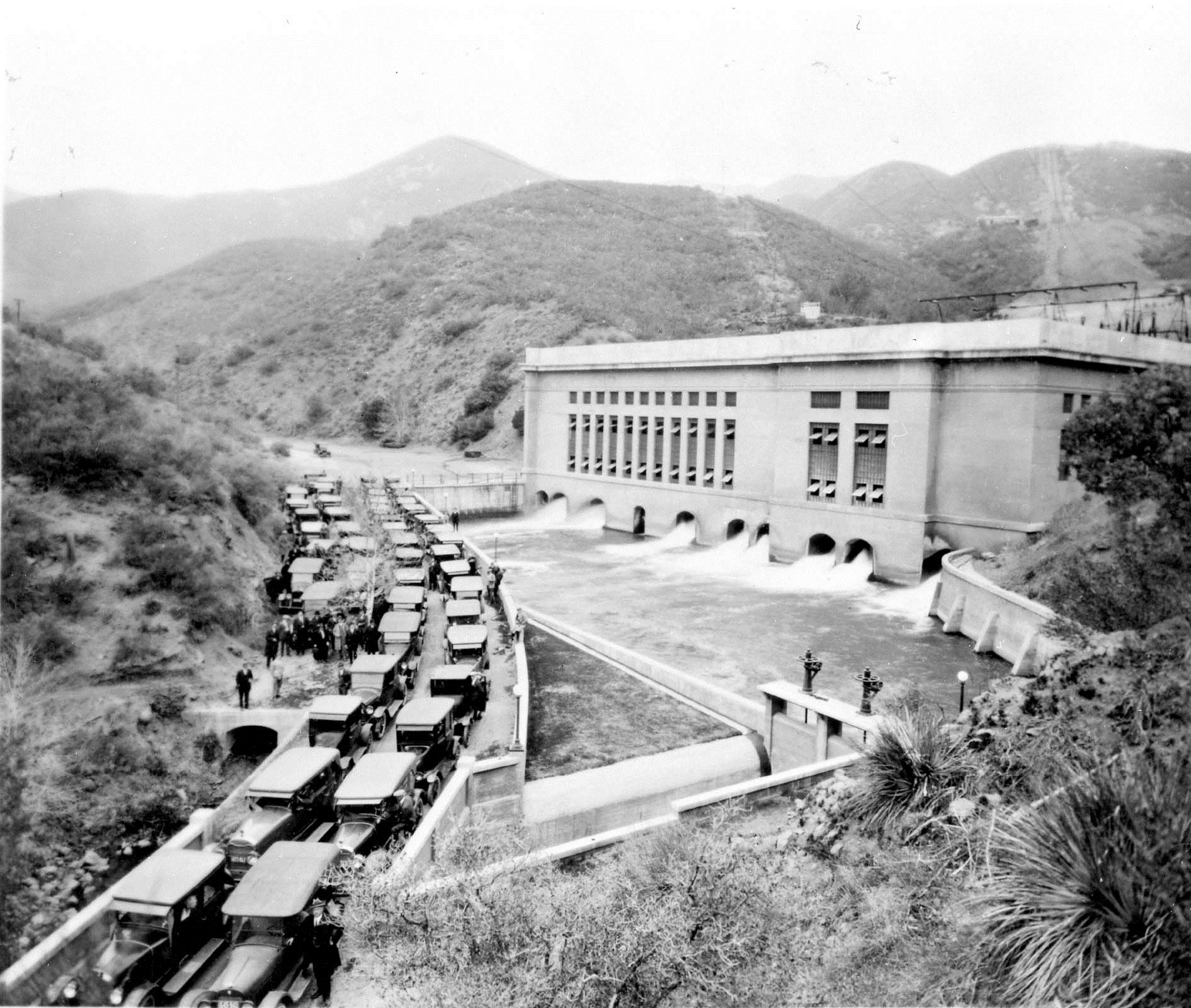

| (1917)* - Opening of the San Francisquito Power Plant No. 1 on March 18, 1917. Construction of the plant began six years earlier in 1911. |

Historical Notes On March 18, 1917 the San Francisquito Power Plant No. 1, Unit 1 was placed in service and energy was delivered to Los Angeles over a newly constructed 115 kV transmission line. The 200 kilowatts generated by Unit 1 were the first commercial kilowatts generated by the Los Angeles Bureau of Power and Light (Click HERE to see more in Early Power Transmission). Subsequently on April 28 and April 16, 1917, Units 2 and 3 respectively were placed in operation. The LA Bureau of Power and Light now had a source of low cost electricity and more than enough power to meet the City's needs. It would sell its excess San Francisquito generated power to Pasadena over two newly constructed 34 kV lines between the two cities. By 1917, World War I had forced the price of fuel oil to rise making the new lower cost hydroelectric power extremely desirable.^ |

Click HERE to see more in Electricity on the Aqueduct |

* * * * * |

River Power House (1917)

|

|

| (1917)** - View showing painters putting the finishing touches on River Power Plant located on the north side of the Los Angeles River with the south end of the building toward the stream and the main entrance toward the west. |

Historical Notes Built in 1917 and beginning operation on Dec 22 of that year, the reinforced concrete building was erected by the Bureau of Power and Light, located in Studio City near the corner of Diaz Avenue and Ventura Blvd along the Los Angeles River. The plant cost $120,000 and created 4000 watts of electrical energy. In 1937, Diaz Ave was renamed Coldwater Canyon Ave. |

|

|

| (1917)** - View showing City officials posing in front of the hydroelectric power plant. |

Historical Notes Water was channeled to the Los Angeles River and sent to the Buena Vista pumping plant in Elysian Park. From Elysian Park, the water could be sent to either east Los Angeles or to the Franklin Canyon Reservoir and then into the west side water system.** |

.jpg) |

|

| (1938)** - View showing H. E. Thompson closing the control valves at the River Power House. |

San Fernando Power House (1917)

|

|

| (1917)** - The San Fernando Power House in Sylmar under construction by the Bureau of Power and Light. The tail race is visible in the foreground. |

San Francisquito Power Plant No. 2 (1928)

|

|

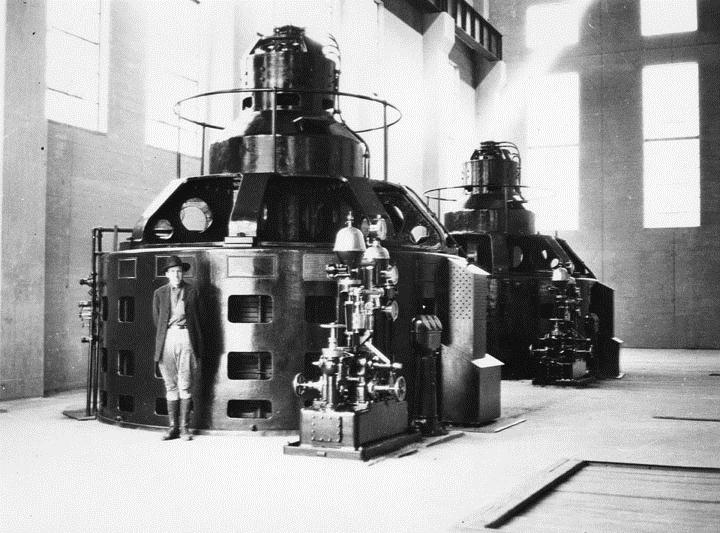

| Man standing by generators (1928)* - St. Francis Dam in San Francisquito Canyon near Saugus was completed in 1926 and failed in 1928. It was part of the Owens Valley Aqueduct System. This pre-failure photograph shows a man standing by 2 hydroelectric generators in Power Plant No. 2. The plant was destroyed when the St. Francis Dam failed on March 12, 1928. By November 1928, this plant was completely restored and back in service. |

Big Pine Power Plant (1928)

|

|

| (1928)* - Big Pine Power Plant on June 7, 1928, operated by the Municipal Bureau of Power and Light. It had a generating capacity of 4200 horsepower.* |

Seal Beach Power Plant (ca. 1928)

|

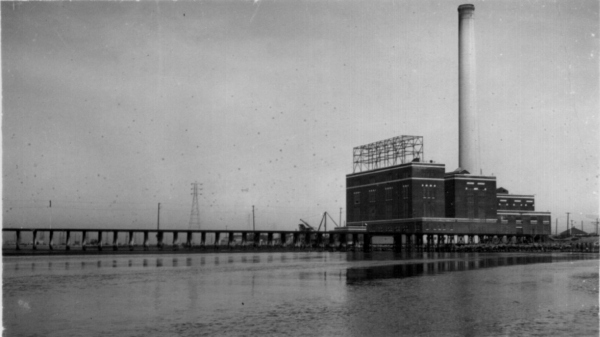

(ca. 1928)* - Exterior view of the LA Gas and Electric Corporation Steam Plant with its prominent smokestack, in Seal Beach. The plant was built in 1925 at a cost of nearly $14 million.

|

Historical Notes In 1936, DWP bought the LA Gas and Electric Corporation and in 1937 assumed ownership of the Seal Beach steam plant. |

|

|

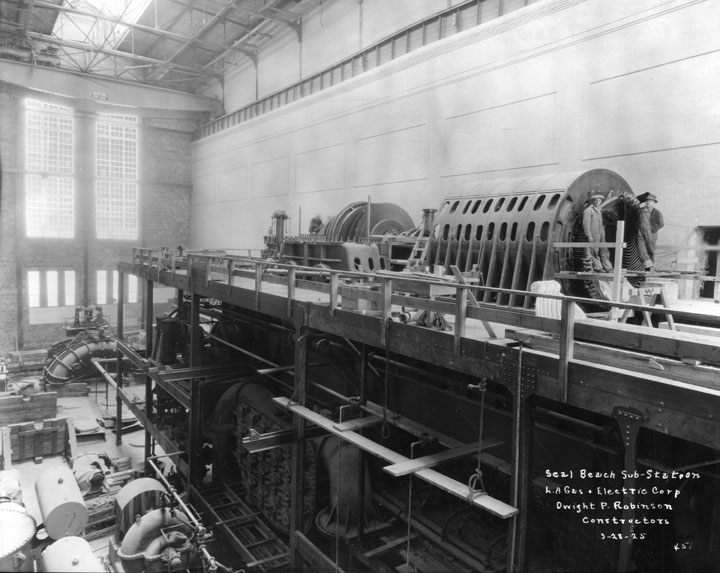

| (1925)* - Interior view of LA Gas and Electric's Seal Beach Sub Station. |

|

|

| (ca. 1928)^^ - View showing the Seal Beach Power Plant and the Ocean Avenue bridge. |

Historical Notes Built in 1924 for the former Los Angeles Gas & Electric Corporation, on a 14 acre tract near Ocean Ave and First Street, the Seal Beach Steam Generating Plant was acquired, along with the Alameda Steam Generating Plant, by the Department when it purchased the electric system of the Los Angeles Gas and Electric and took possession of the properties February 1, 1937. The Alameda Street plant was retired from service by Board resolution in 1951. The combined capacity of the two generators at the Seal Beach plant was 75,000 kilowatts.*^ |

|

|

| (ca. 1934)^^ - View of the Seal Beach plant now with a shorter smokestack (see previous photo). |

Historical Notes The original smokestack was damaged during the 1933 Long Beach Earthquake and replaced with a much shorter one as seen above. The Stanton House stands across from the plant on the right. The Seal Beach plant was taken out of service and demolished in 1967.^^ |

|

|

| (1940)* - The Seal Beach plant showing its new Municipal Light and Power sign. The plant was retired from service in 1951. |

Alameda Power Plant

|

|

| (1930s)* - View of the Alameda Steam Generatin Plant before it was purchased from Los Angeles Gas and Electric Corporation by the Municipal Light and Power (later DWP). |

Historical Notes The Alameda Steam Generating Plant was acquired, along with the Seal Beach Steam Generating Plant, by the Department when it purchased the electric system of the Los Angeles Gas and Electric and took possession of the properties February 1, 1937. The Alameda Street plant was retired from service by Board resolution in 1951.* |

|

|

| (1930s)* - View of the Alameda Steam Plant cooling towers with early model cars parked on the street. |

Hoover Dam Power Plant (1936)

|

|

||

| (1930)* - Black Canyon and the Colorado River before construction of Hoover Dam. | (1934)*^ - Black Canyon with Hoover Dam beginning to take form. |

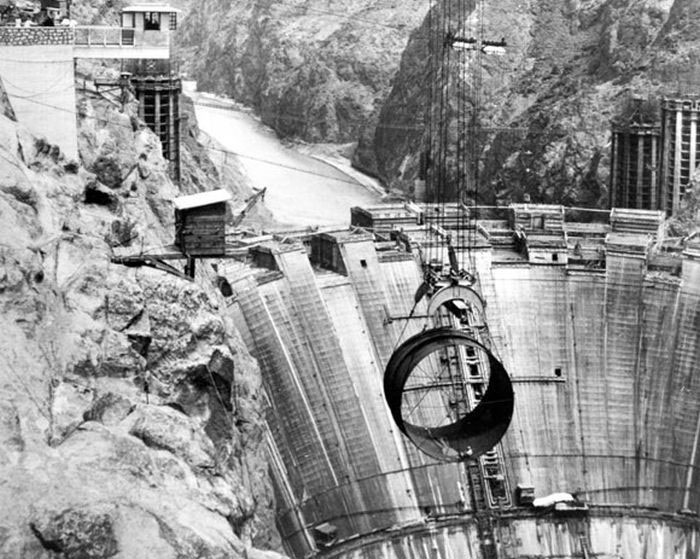

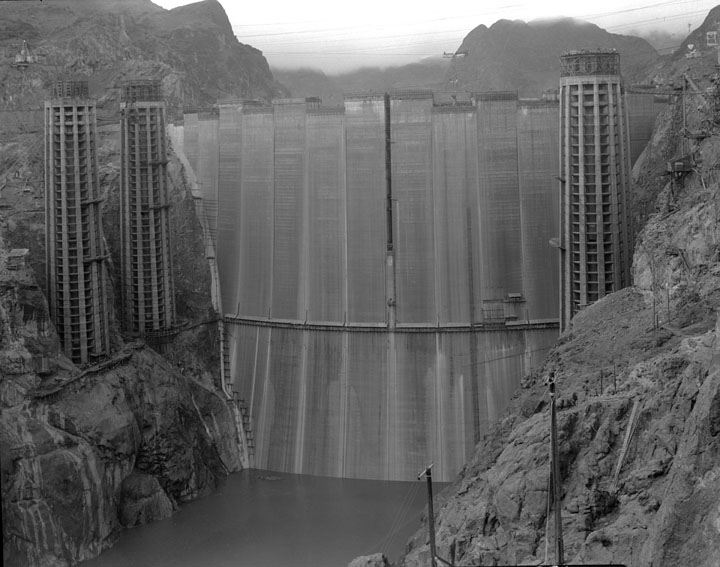

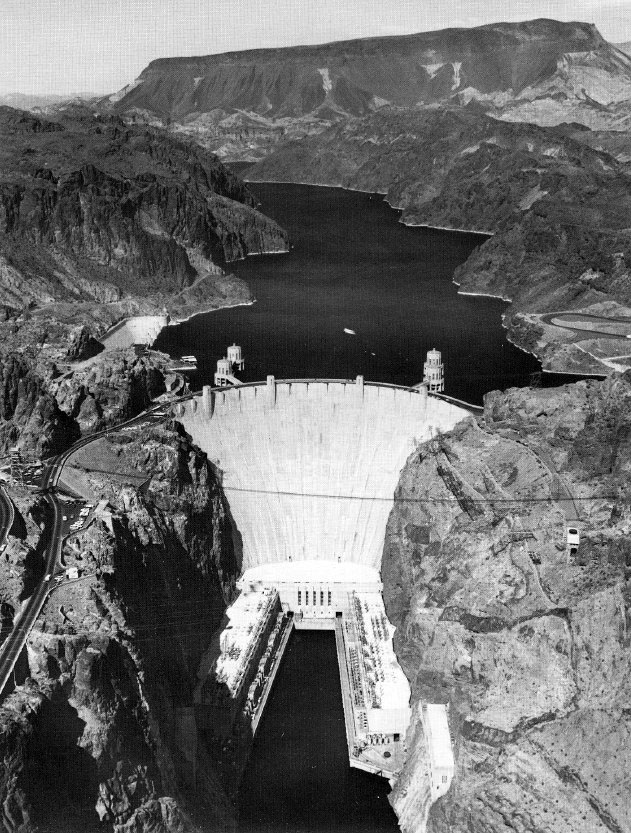

BackgroundHoover Dam was constructed between 1931 and 1936 during the Great Depression. Its main purpose was to harness the Colorado River to prevent periodic catastrophic flooding, to allocate and distribute water, and to generate hydroelectricity for the Southwest. Even by today's standards Hoover Dam was a gigantic project. At the time it was the world's largest project made with concrete, not to mention the largest public works project in US history. The dam's completion had a significant impact on Southern California and in particular Los Angeles, since the power generated by the dam contributed to more than 70% of the City's power needs at the time. |

|

|

| (1935)^.^ – Penstock pipe section being lowered into the canyon by a 150-ton capacity cableway, then carried in the tunnels on railroad cars. |

Historical Notes Forty-four thousand tons of steel were formed and welded into 14,800 feet of pipe varying from 8 1/2 to 30 feet in diameter. Each length of the largest pipe - 12 feet long, 30 feet in diameter, and 2 3/4 inches thick - was made from 3 steel plates, of such weight that only two plates could be shipped from the steel mill to the fabricating plant on one railroad car. Two such lengths of pipe welded together make one section weighing approximately 135 tons or, at intersections with the penstocks, as much as 186 tons. |

|

|

| (1935)* - View of the Hoover Dam power plants near completion. The concrete pouring process appears to be complete. |

Historical Notes A total of 3,250,000 cubic yards of concrete was used in the dam before concrete pouring ceased on May 29, 1935. In addition, 1,110,000 cubic yards were used in the power plant and other works. More than 582 miles of cooling pipes were placed within the concrete. Overall, there is enough concrete in the dam to pave a two-lane highway from San Francisco to New York.^ |

|

|

| (1935)* - View showing Hoover Dam close to completion. Note the height of the intake towers (395 ft tall). |

|

|

| (ca. 1938)^^# – Aerial view showing a completed Hoover Dam with Lake Mead filled to capacity behind it. |

Historical Notes Hoover Dam, one of the world’s outstanding engineering achievements, was selected by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1955 as one of America’s seven modern civil engineering wonders. Majestic in its clean graceful lines, the dam stands with one shoulder against the Nevada wall and the other against the Arizona wall of Black Canyon, harnessing the Colorado River.^ |

|

|

| Detailed drawing of the dam and power plant. Source: U.S. Department of Interior |

|

|

| (September 30, 1935)* - Dedication of Hoover Dam by President F. D. Roosevelt. Ezra Scattergood can be seen in the lower right behind the chair with the hat. |

Historical Notes On September 30, 1935, less than 5 years after construction started, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in dedication ceremonies at Hoover Dam: “This is an engineering victory of the first order – another great achievement of American resourcefulness, skill and determination. This is why I congratulate you who have created Boulder Dam and on behalf of the Nation say to you, ‘well done’.” ^## In 1920, Ezra Scattergood pushed for a bill authorizing the construction of the Boulder Canyon Project (Hoover Dam). Despite attempts to discredit the project, Scattergood helped convince Congress in 1928 to pass the legislation and allow construction of the dam and a hydroelectric power plant.^# |

|

|

| (1936)* - Front shot showing all 12 valves in canyon wall outlet working simultaneously and discharging Colorado River water. In the future the valves would be used only in emergencies, the tremendous power of the falling waters being carried by huge steel penstocks to turn the turbine wheels of fifteen 115,000 horsepower generators such as those shown in inset. On October 9 the second generator in this row flashed to Los Angeles the Power Bureau’s first allotment of Boulder power.*^ |

|

|

| (1940)*^ - Tourists gather around one of the eight generators in the Nevada wing of the powerhouse to hear its operation explained. The Arizona side has nine generators |

Historical Notes The powerplant consists of 17 main Francis turbine generators and two Pelton Waterwheel station service units (one for each plant wing). The total plant capacity is 2,079 MW. |

|

|

| (1930s)**^ – View showing the high-voltage switching yard at Boulder Dam, with the steel etched against a black desert sky. Power from the generators at the top of Boulder Dam left this station on the main line to Los Angeles at 287,500 volts. |

|

|

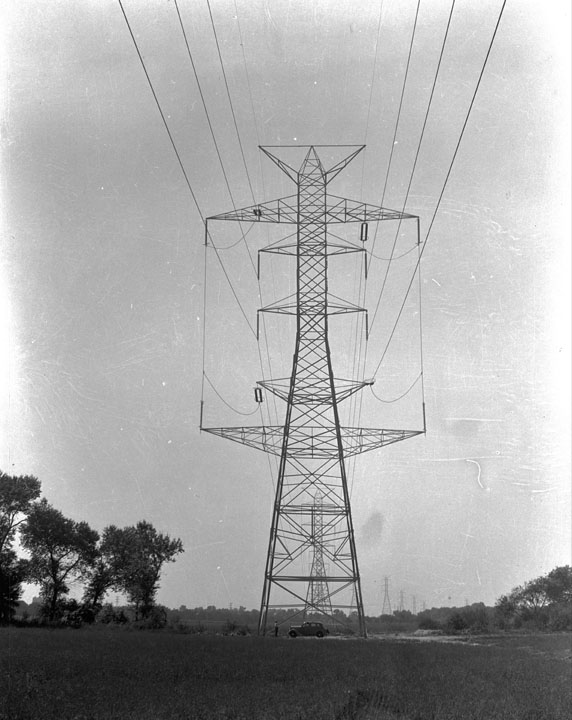

| (1935)* - Double-circuit tower carrying 287,000 volt lines from Boulder Dam to Los Angeles. |

Historical Notes Sixteen high-voltage transmission lines connect Hoover Dam with its power market area. Two lines terminate at Los Angeles, a distance of 266 miles. A third line extends to Los Angeles via the McCullough Switching Station, where the energy is stepped up to 500,000 volts. One line extends to San Bernardino, California. Three lines extend to Las Vegas, Nevada. One of the latter connects with the Davis Dam transmission system. Other lines extend to Kingman, Arizona; Needles, California and nearby Boulder City. In total, there are 2700 miles of transmission line cable sending electricity from Hoover Dam to Los Angeles. Click HERE to see more in Early Power Transmission. |

|

|

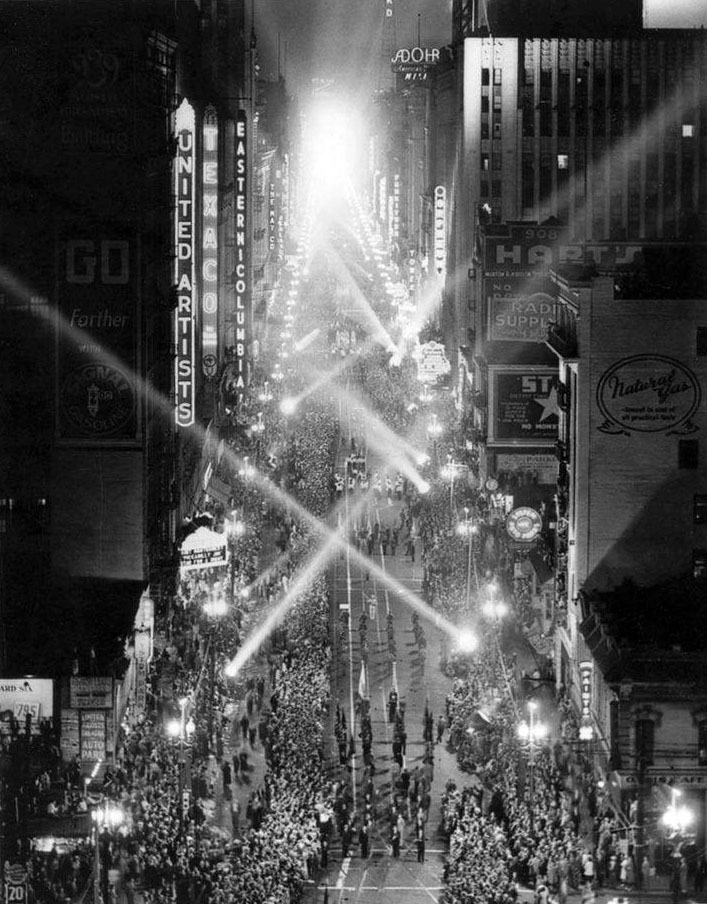

| (1936)## - View showing the parade down Broadway (aka "The Light on Parade") celebrating Los Angeles' new source of electricity after the completion of Hoover Dam. |

Historical Notes On October 9, 1936, the switch was thrown and electricity generated at the new Hoover Dam arrived in Los Angeles. Los Angeles threw a big party. The “Light on Parade” proceeded down Broadway, nicknamed “the Canyon of Lights.” |

Click HERE to see more in Construction of Hoover Dam |

* * * * * |

Harbor Steam Plant (ca. 1942)

|

|

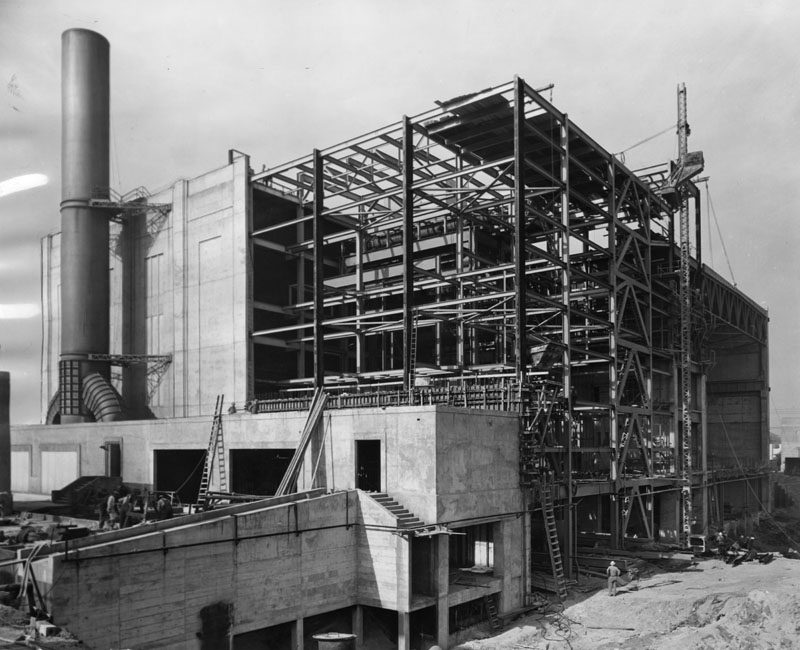

| (ca. 1942)* - View of the Harbor Steam Plant Unit No. 1 under construction. |

Historical Notes Construction of the plant was started early in 1932 and a few months later was halted by injuction proceedings. The Bureau was successful in establishing its right to build the plant and the injuction was dissolved, but later in the year an agreement was entered into for purchase of necessary energy and the steam plant construction program was postponed in favor of concentrating the Bureau’s efforts upon development and utilization of Boulder Dam power.*^ |

|

|

| (1947)* - View showing progress on construction of the first addition to the Department of Water and Power Harbor Steam Plant in Wilmington. The new wing housed a second 65,000 kilowatt steam-turnine generator. |

|

|

| (1948)* - Exterior view of the art deco style Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Harbor Steam Plant building taken during its construction. |

|

|

| (1949)*^ - Interior view of Harbor Steam Plant showing Unit No. 5 (foreground) in its final stages of installation. |

Historical Notes Completing an eight-year construction program that was started in April of 1941, suspended through the war years and delayed through many months of the postwar period by scarcity of materials, equipment and manpower, Unit No. 5 at the Department’s Harbor Steam Plant was placed in service and synchronized to the system on the afternoon of July 5, 1949.*^ |

|

|

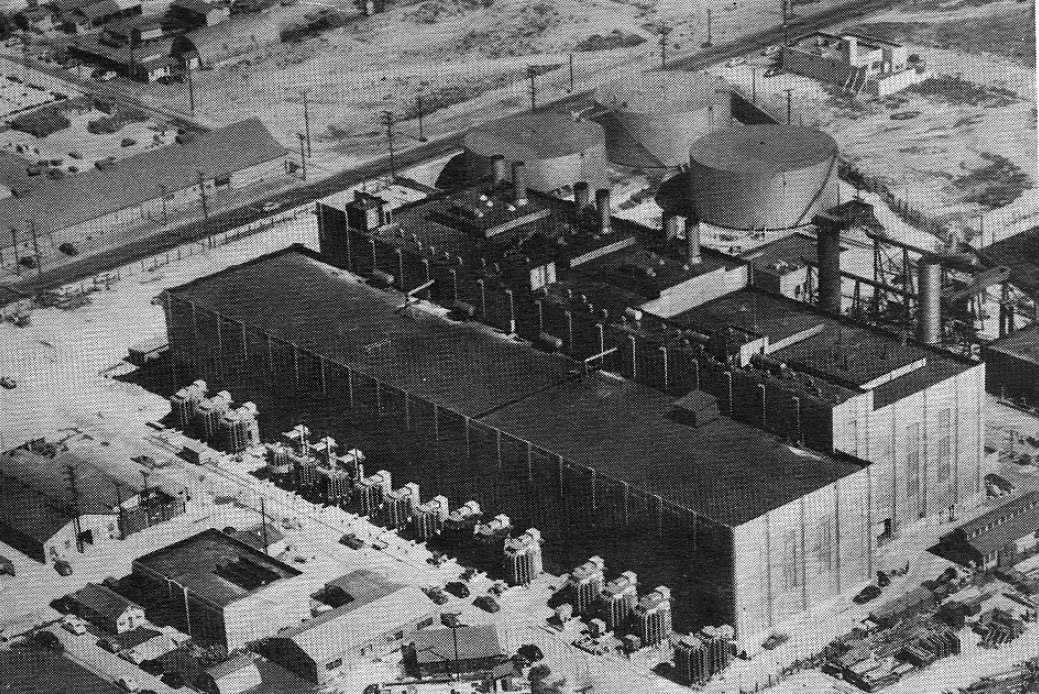

| (ca. 1950)*^ – Aerial view showing a completed Harbor Steam Plant with all five turbines in operation. |

Valley Steam Plant (1953)

|

|

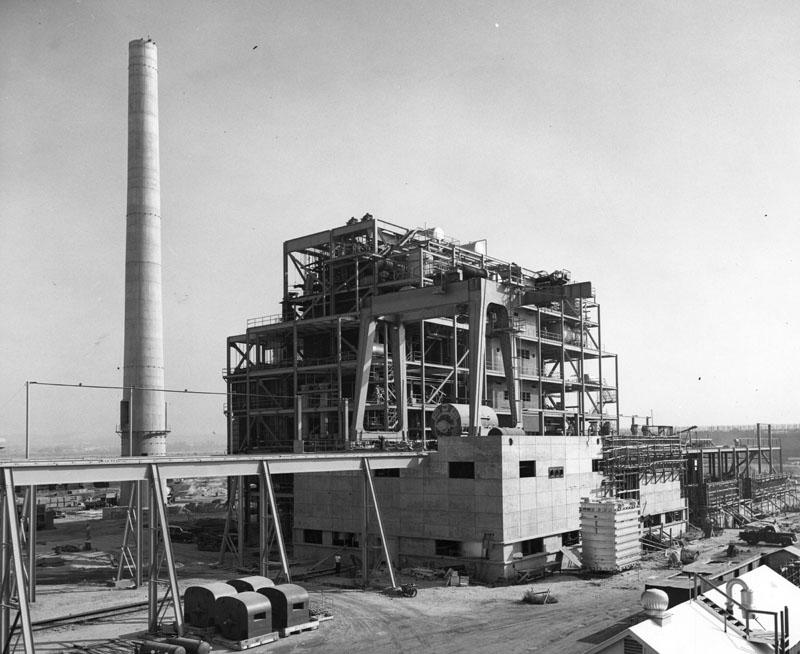

| (1953)* - The Valley steam electric generating plant under construction in the San Fernando Valley. |

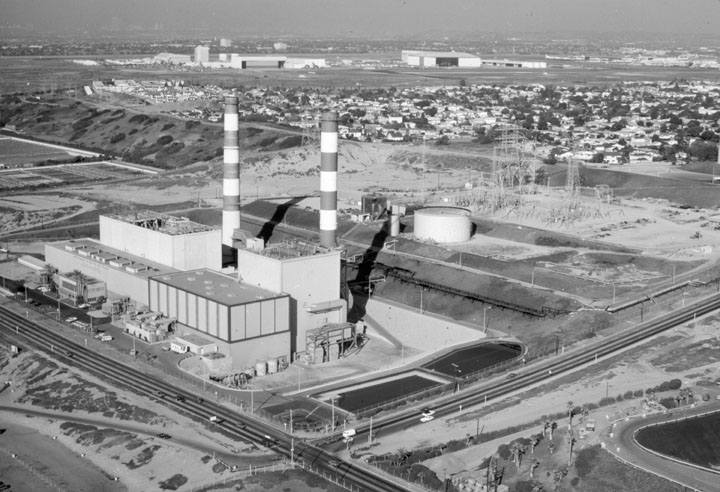

Historical Notes The 1950s saw such a rapid growth in the San Fernando Valley that it forced the Department of Water and Power to construct one of the largest steam plants in the country, located in Sun Valley. |

|

|

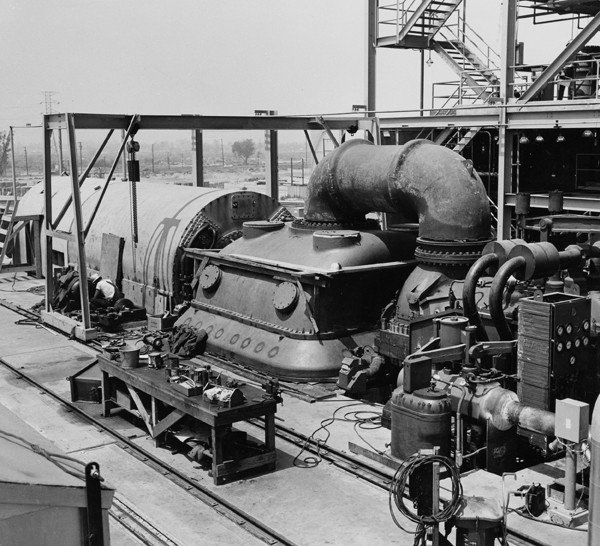

| (1954)*** - View showing a General Electric F2 type turbine with a hydrogen cooled generator (Unit No. 1) at Valley Steam Plant. |

|

|

| (1955)* - Workmen haul the last of four electric generators into position at the $80,000,000 Valley Steam Plant. |

|

|

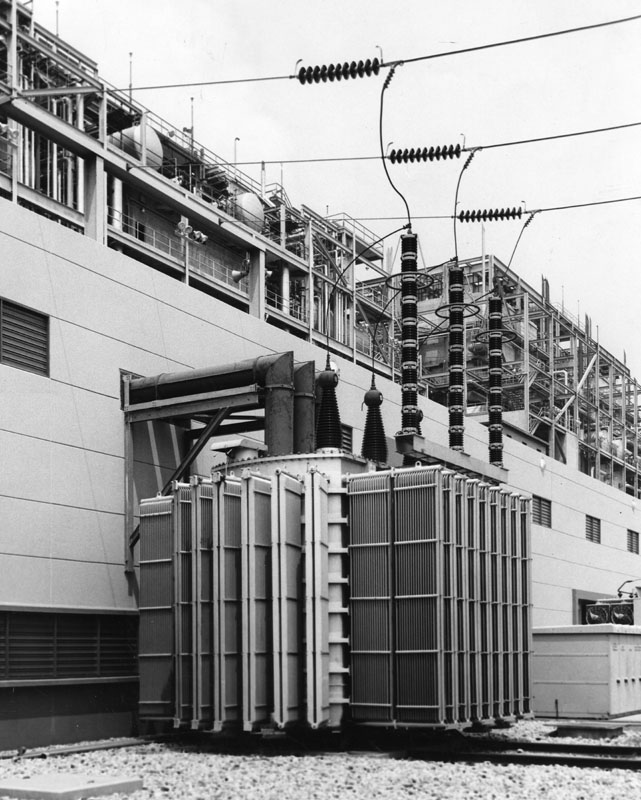

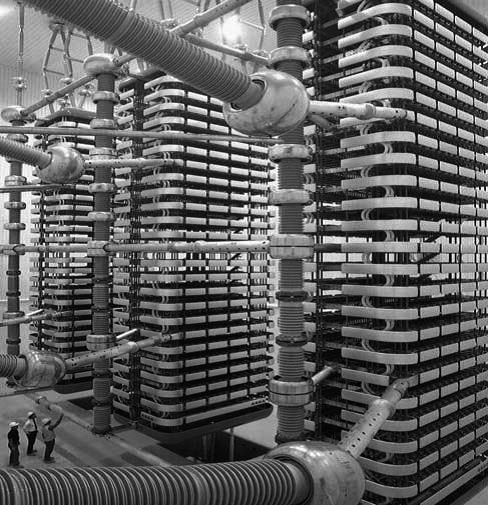

| (1957)* - This huge 25-foot three-phase transformer at the Valley Steam Plant steps up voltage from 18,000 to 138,000 volts for transmission to the distribution system. The plant has about 1700 control switches, instruments and relays. |

|

|

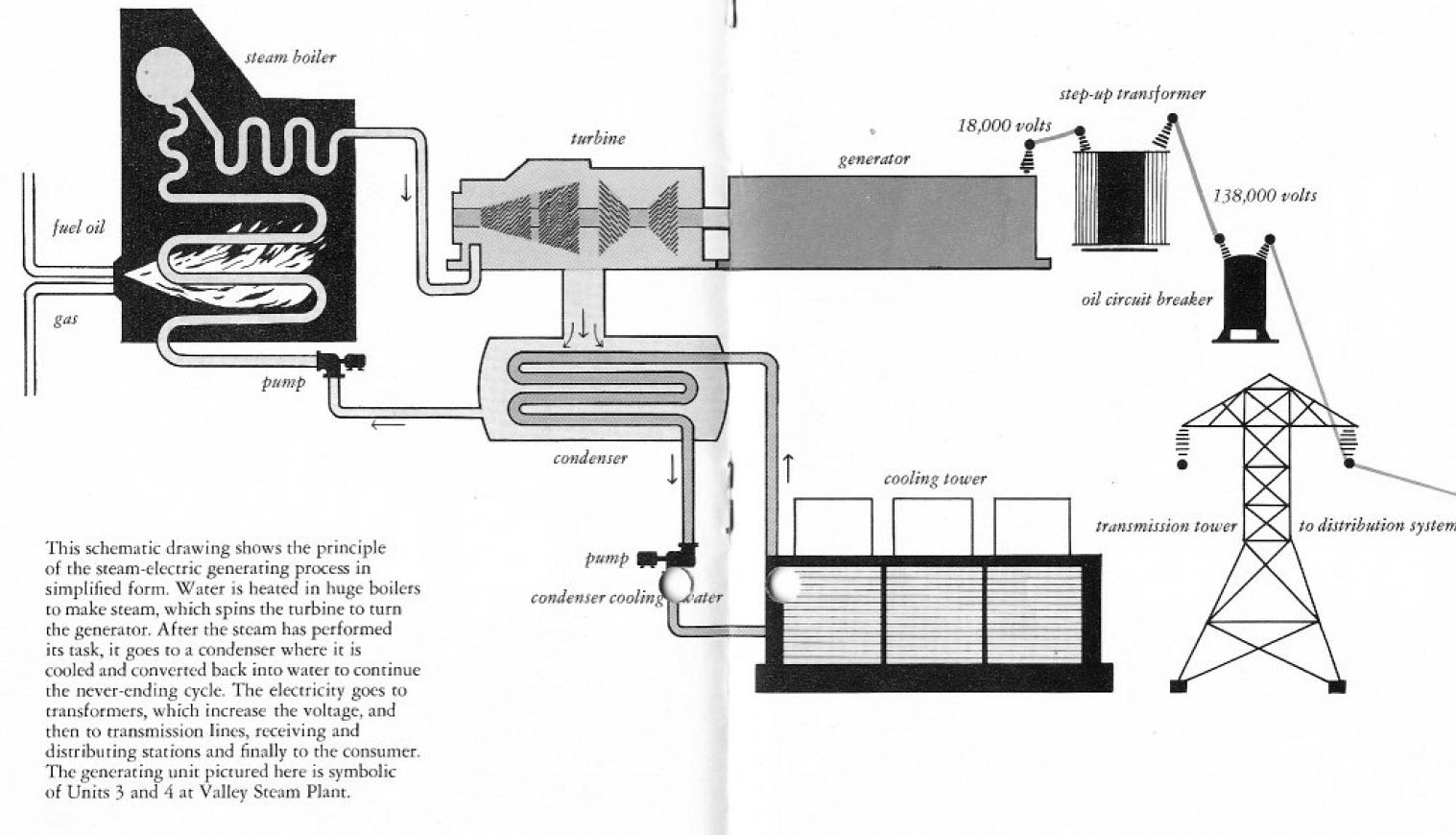

| (1957)*^ – Schematic drawing showing the principle of the steam-electric generating process in simplified form. The generating unit pictured here is symbolic of Units 3 and 4 at Valley Steam Plant. |

Notes Water is heated in huge boilers to make steam, which spins the turbine to turn the generator. After the steam has performed its task, it goes to a condenser where it is cooled and converted back into water to continue the never-ending cycle. The electricity goes to transformers, which increase the voltage, and then to transmission lines, receiving and distributing stations and finally to the customer.*^ |

|

City and business officials dedicate the new Valley Steam Plant at 11805 Sheldon Street on May 18, 1957.

|

| (1957)* - From left are Lester Pickup, manager, Valley division, Southern California Gas Co.; Councilman Everett Burkhalter; Col. George F. Herbert, administrative assistant to Mayor Norris Poulson; William S. Peterson, general manager, Department of Water and Power; and J. C. Moller, president, Board of Water and Power Commissioners.* |

|

|

| (1956)* - View showing the newly completed Valley Steam Plant with its four smokestacks, in the San Fernando Valley. |

|

|

| (1956)*^* - Photograph caption dated July 13, 1956 reads "Power for million lights up sky. Fabulous growth of the San Fernando Valley forced the Department of Water and Power to construct one of the largest steam plants in the country in Sun Valley. The four unit project costing $89,000,000 is virtually completed and will provide power for million Valley residents." - Valley Times |

|

|

| (1956)*^* - Photo caption reads, "Valley Steam Plant glows with thousands of lights during nighttime operation. Pipes and valves in foreground are part of fuel lines leading to plant. Built on 150-acre site in Sun Valley at cost of $80,000,000, Valley Steam Plant has total generating capacity of 512,000 kilowatts of electricity. Because of mild climate, plant is virtually open to the air with complete housing only for operating personnel and most delicate equipment. Electricity is generated by means of turbines which are powered by super-heated steam, heated in boilers using either gas or oil as fuel." Valley Times - August 1, 1956 |

|

|

| (ca. 1957)*^^ - View showing the front entrance to Valley Steam Plant at 11805 Sheldon Street. |

Scattergood Steam Plant (1957)

|

|

| (1957)^* - Aerial view showing the early construction stages of Scattergood Steam Plant at Playa Del Rey. Photographer: Sandusky; Date March 14, 1947. |

|

|

| (1958)* – Aerial view looking east showing the Scattergood Steam Plant construction site, located at 12700 Vista Del Mar in the city of Playa Del Rey. Photograph dated January 14, 1958. |

|

|

| (1958)* - Profile view looking south showing Scattergood Steam Plant under construction. |

|

|

| (1968)* - Aerial view looking east at the Scattergood Steam Plant, located on a 57-acre site facing the ocean front south of the Playa del Rey district of Los Angeles. |

Historical Notes Commercial operation of the Department’s huge new Scattergood Steam Plant began on December 7, 1958 with the synchronizing of unit No. 1 to the Power System, following a series of shakedown test runs. The powerful turbine-generator has a capability of 160,000 kilowatts when operating at capacity.*^ Scattergood Steam Plant was formally dedicated on September 10, 1959. Click HERE to see Dedication Program. |

|

|

| Scattergood Steam Plant after completion of Unit No. 2.* |

|

|

| (1968)* - Interior view of Scattergood Steam Plant showing one of its generators. |

Notes

In the 1950s and 1960s, DWP added a number of power plants, including the Owens River Gorge Hydroelectric Project, Valley Generating Station, Scattergood Generating Station, and Haynes Generation Station to accommodate the growing electrical power needs of Los Angeles.

Click HERE to see more in Electricity on the Aqueduct |

Intermountain Power Project (1982)

|

|

| (1980s)^^ – Cranes surround the steel structure of Intermountain Power Project Unit One. The plant was erected using 70,000 tons of structural steel with the boiler support girders weighing 200 tons each and set at an elevation of 301 feet above sea level. |

Historical Notes The Intermountain Generating Station is the central component of Intermountain Power Project (IPP), a $4.5 billion project to supply electricity to Southern California and other markets. It is located near Lynndyl, Millard County, Utah. |

|

|

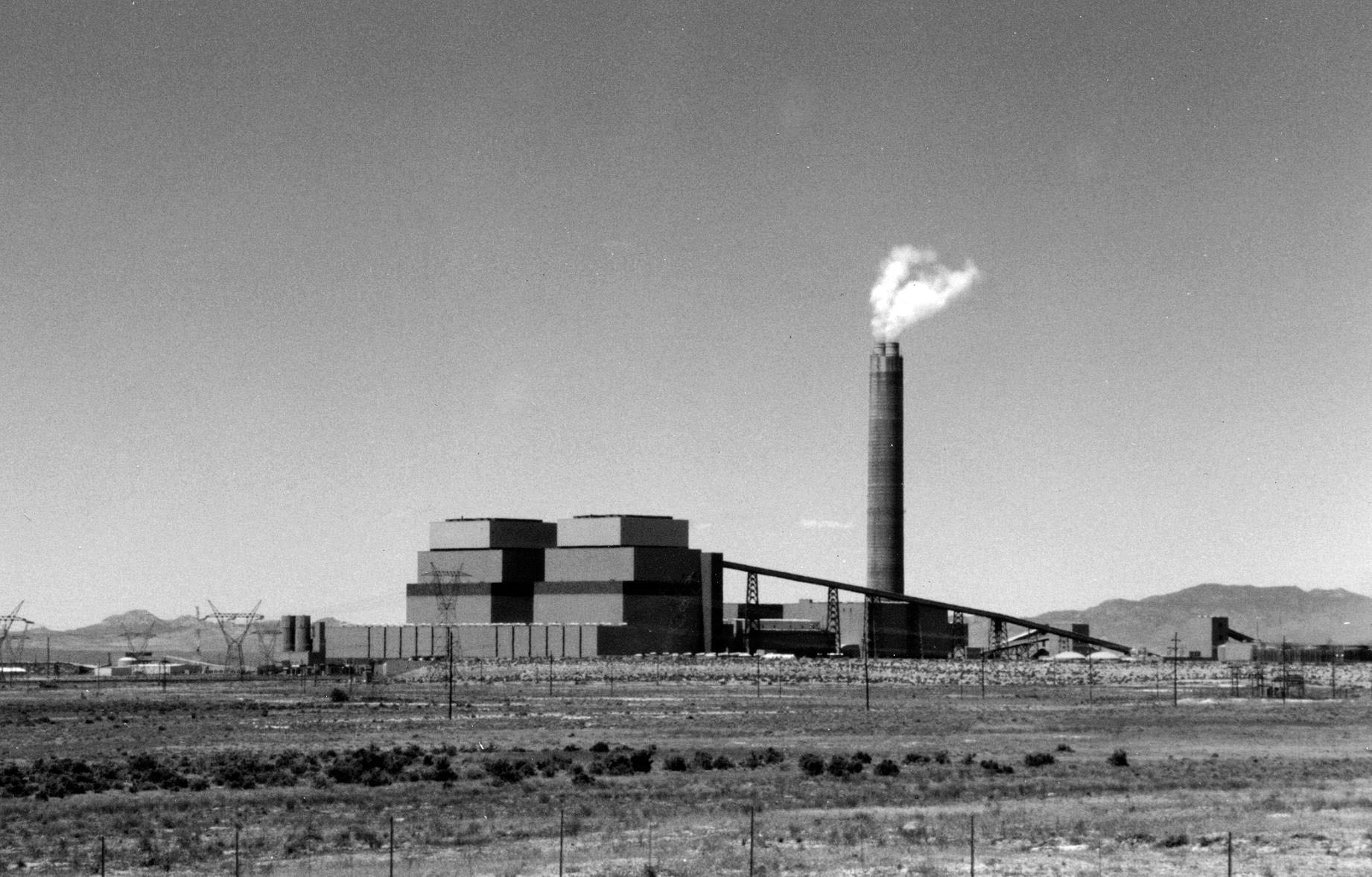

| (1980s)#* – Aerial view showing Intermountain Power Project (IPP) located in Utah. |

Historical Notes The plant was built in the remote part of west-central Utah, in the Sevier Desert, and is connected directly to the edge of Los Angeles by a 490 mile long high voltage DC line. The massive coal-fired power plant produces over 1,800 megawatts of power, and is supplied by coal mines in central and eastern Utah. |

|

|

| (n.d.)#* – View showing train coal delivery at Intermountain Power Project. Truck delivery is also utilized.. |

Historical Notes One of Utah's largest coal-fired power plants — the Intermountain Power Project outside Delta — will cease operations by 2025. Due to a law passed in 2006 by the California legislature which forbid any new contracts for coal-fired power from any utility or municipality, the owners decided to repower the facility to burn natural gas. While electricity will no longer flow from heating coal, IPP participants are moving ahead with plans to develop new natural gas-fueled electricity generation at the site. The new project will bring on 1,200 megawatts of new natural gas-fueled electricity, compared with the 1,800 megawatts of installed capacity from coal-fired generation.^ |

|

||

| (1980s)#* – View showing the Converter Station Valve Hall which converts the Power Plant's generated power from AC to DC before being transmitted to Southern California. |

Historical Notes Intermountain Power Project is connected directly to the edge of Los Angeles via a 490 mile long high voltage DC line. The three main components of the Intermountain Power Project are located primarily in Utah and California. The Generation Station is located near Lynndyl, Millard County, Utah. The Southern Transmission System ( the "STS" extends approximately 490 miles from the Generation Station to Adelanto, California with an alternating current/direct current converter station at each end. The Northern Transmission System (the “NTS”) consists of two segments. The first segment, consisting of two parallel 345-kV AC transmission lines, extends approximately 50 miles from the Generation Station to a switchyard located near Mona, Utah. The second segment, consisting of a single 230-kV AC transmission line, extends approximately 144 miles from the Generation Station to the Gonder Switchyard located eight miles north of Ely, Nevada. |

|

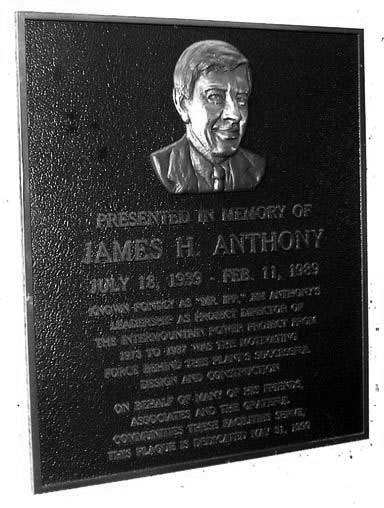

(1989)#* - Plaque commemorating James H. Anthony, Construction Project Director at IPP. | |

Historical Notes James H. Anthony was Project Director of IPP from 1973 to 1989 and the motivating force behind the successful design and construction of the Project. A plaque in his honor was placed in the foyer of the IPSC Administration Building. |

|

|

| (2010s)^.^ – Ground view showing Intermountain Generating Station with its flue gas stack standing over 700 feet tall. |

Historical Notes The power plant consists of two units each with a generation capacity of 950 MW. Generating units are equipped with General Electric tandem compound steam turbines and Babcock & Wilcox subcritical boilers. The boiler houses of Intermountain Power Project are 301.0 feet and the flue gas stack is 701.0 feet tall. The HVDC Intermountain transmission line runs between Intermountain Generating Station and Adelanto Converter Station in Adelanto, California. |

|

|

| (2014)*^ –Aerial view of the Intermountain Power Project, located in the heart of Utah, in Millard County. Its operations are overseen by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Currently burning coal. It will be converted to natural gas by 2025. |

Historical Notes The Intermountain Power Agency, located in Utah, is a power generating cooperative of 23 municipalities in Utah and 6 in California. It owns the Intermountain Power Project near Delta, Utah, one of the largest coal-fired power plants in the United States. About 75 percent of the generated power is purchased by cities in Southern California and the remainder is purchased by cities, cooperatives and Pacificorp in Utah and a cooperative in Nevada. The IPA also runs transmission lines to Mona, Utah, to Adelanto Converter Station in Adelanto, California and near Ely, Nevada. |

|

|

| (2019)^.^ – Intermountain Power Plant outside Delta, Utah, has been a major source of electricity for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power since the 1980s. The coal-burning facility is scheduled to be converted to natural gas by 2025. |

Historical Notes In 2013, the Los Angeles City Council approved a plan to convert the facility from coal to natural gas by 2025, at an estimated cost of $500 million. Click HERE to see the History of Intermountain Power Project (1982 - 2015) |

* * * * * |

Corral Canyon Nuclear Power Plant (Proposed—but never built)

|

|

| (1963)* – View showing an exhibit promoting the virtues of a nuclear power plant which DWP proposed to build in the canyons of Malibu. |

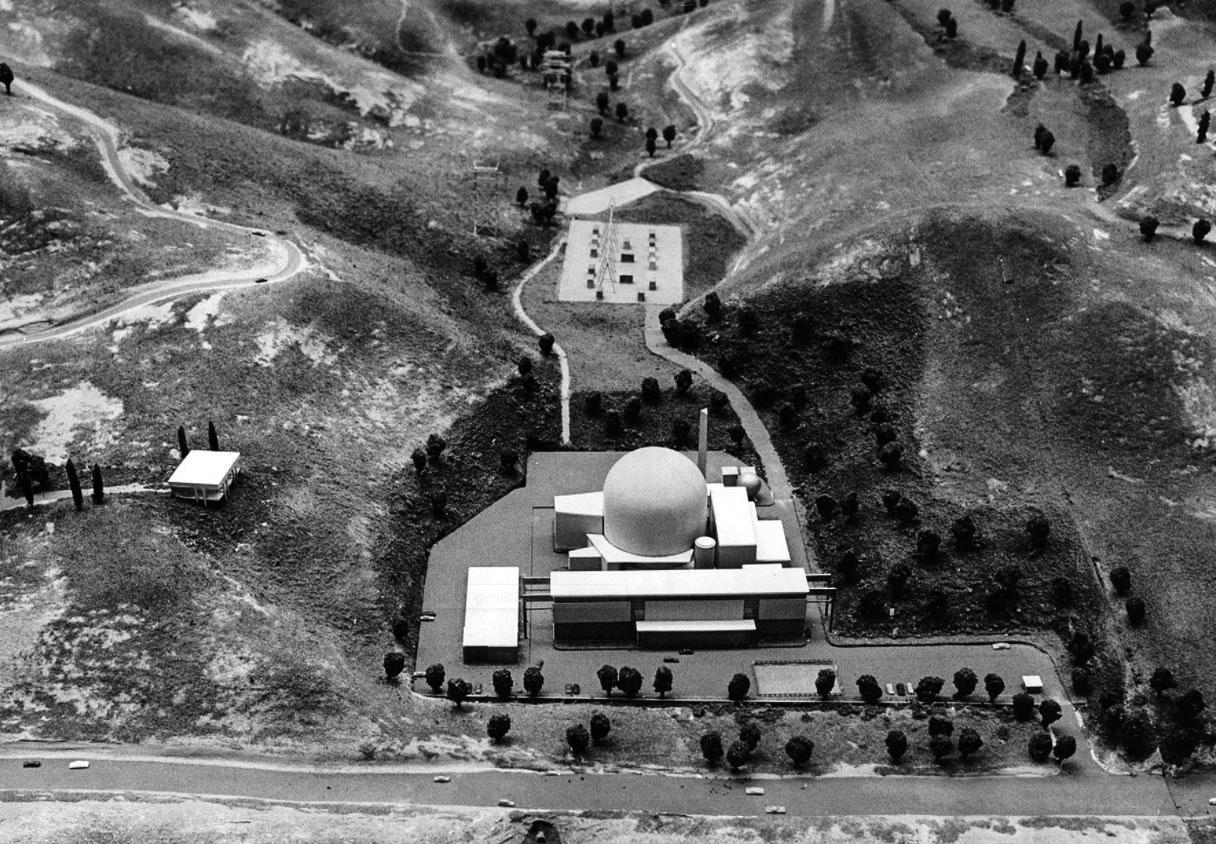

Historical Notes In 1963, Los Angeles officials proposed building a San Onofre-style atomic generating plant in Corral Canyon as a solution to the fast-growing city's need for more electricity. The atomic plant would be tucked between hillsides at the bottom of a deep ravine. Seawater pumped from pipes buried under Pacific Coast Highway and the beach and extending half a mile into the ocean would cool the reactor. |

|

|

| (1965)* – The model for a proposed nuclear power plant near Malibu shows the surrounding area, including a golf course projected to be developed by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. This photo appeared in the June 21, 1965, edition of the Los Angeles Times. |

Historical Notes DWP engineers viewed nuclear power as the perfect solution to a looming electricity shortage. The Corral Canyon plant would be larger than any atomic plant in existence and would have the capacity to generate about 20 percent of the power for every home, office and factory in Los Angeles, the agency predicted. Unlike oil- and coal-powered generating stations, the atomic plant would be pollution-free and would not contribute to the smog that was blanketing Los Angeles almost daily. Corral Canyon’s isolation was another plus. The atomic plant would be tucked between hillsides at the bottom of a deep ravine. Seawater pumped from pipes buried under Pacific Coast Highway and the beach and extending half a mile into the ocean would cool the reactor. The plant’s electricity would be carried into Los Angeles by a line of steel transmission towers constructed across the Santa Monica Mountains through Calabasas and connected to the DWP’s existing electric grid in the San Fernando Valley. The deal sounded sweet to Los Angeles officials for other reasons as well. The federal Atomic Energy Commission was willing to classify the Corral Canyon reactor as a nuclear power demonstration project. As such, the commission would pay up to $8 million for the design of the plant and would waive fuel-use charges of up to another $8.2 million. City officials thought at first that the atomic plant plan would sail through federal and local reviews. In 1963, they entered into a tentative agreement with the Westinghouse Corp. to buy the generating equipment. The Atomic Energy Commission named a Boston company to design and build the reactor. Officials announced that the plant would be completed by 1967. But the proposal quickly caused a furor in Malibu, helping galvanize a fledgling environmental movement, leading to the creation of a vast network of public parkland and land-development restrictions throughout the Santa Monica Mountains — including Corral Canyon. Malibu celebrities joined in public hearings conducted by Los Angeles County to complain that the coastal area was seismically active. In 1970, after six years of debate and dozens of conflicting geology reports over the canyon’s safety, the city quietly dropped an option to buy nearly $100 million worth of equipment that would have launched the first 490,000-kilowatt phase of the atomic plant project. |

* * * * * |

Please Support Our CauseWater and Power Associates, Inc. is a non-profit, public service organization dedicated to preserving historical records and photos. We are of the belief that this information should be made available to everyone—for free, without restriction, without limitation and without advertisements. Your generosity allows us to continue to disseminate knowledge of the rich and diverse multicultural history of the greater Los Angeles area; to serve as a resource of historical information; and to assist in the preservation of the city's historic records.

|

History of Water and Electricity in Los Angeles

More Historical Early Views

Newest Additions

Early LA Buildings and City Views

* * * * * |

References and Credits

* DWP - LA Public Library Image Archive

^ Daily Breeze Article (10-5-11)

#*The History of IPSC (1982 - 2015)

^^Seal Beach Founders - http://sbfoundersday.wordpress.com/

** CSUN Oviatt Library Digital Collection (A)

***CSUN Oviatt Library Digital Collection (B)

*^*LA Public Library Image Archive

**^Metro.net - Los Angeles Transit History

*^^DWP - Water and Power Associates Historical Archives - Courtesy of Rex Atwell

^**Huntington Digital Library Archive

^*^LA Public Library Image Archive

^^^LA Times: Still Generating Controversy

**#Noirish Los Angeles - forum.skyscraperpage.com

..... Wikipedia: Electric Power Industry

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Major Efforts

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Board Officers and Directors

- Mulholland/McCarthy Service Awards

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index