Los Angeles River - The Unpredictable!

For centuries, the Los Angeles River has been both a giver and a taker of life. During heavy rains, it transformed into a violent torrent, sweeping away homes, bridges, and farmland. During dry months, it often dwindled to a trickle or spread into marshlands. Its unpredictable nature shaped the history, culture, and urban development of Los Angeles.The Los Angeles River crosses a vast alluvial plain—soil deposited over thousands of years by shifting watercourses. Floods repeatedly forced the river to carve new channels, changing its path through what is now Los Angeles and Orange counties. On average, Los Angeles receives just 15 inches of rain per year, but the surrounding mountains often collect more than 40 inches. Water from elevations near 1,000 feet rushes downhill to sea level in only 50 miles. This steep drop created the perfect conditions for flash floods each winter. |

|

Early History

|

|

| (Early 1900s)* – View shows mud and erosion on the banks near Griffith Park, caused by the flood waters from the Los Angeles River. |

From the DWP Historical Archives The Los Angeles River has often been described as temperamental: “She has changed her name, often her course, and many times the topography of the land she flows through.” The river’s first written record by Europeans comes from August 2, 1769, when Father Juan Crespí of the Portolá expedition described a “beautiful river” lined with cottonwoods and alders. Because the date coincided with the Feast of Our Lady of the Angels of Porciúncula, the expedition named it Río de Porciúncula. His journal noted fertile soil, wild grapes, and rose bushes—factors that later influenced the decision to establish El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Ángeles in 1781. Spanish settlers quickly tapped the river with the Zanja Madre (“Mother Ditch”), an irrigation system that supplied water to crops and the pueblo. But as they soon learned, the river was prone to dramatic floods.

|

Great Floods of the 19th Century

|

|

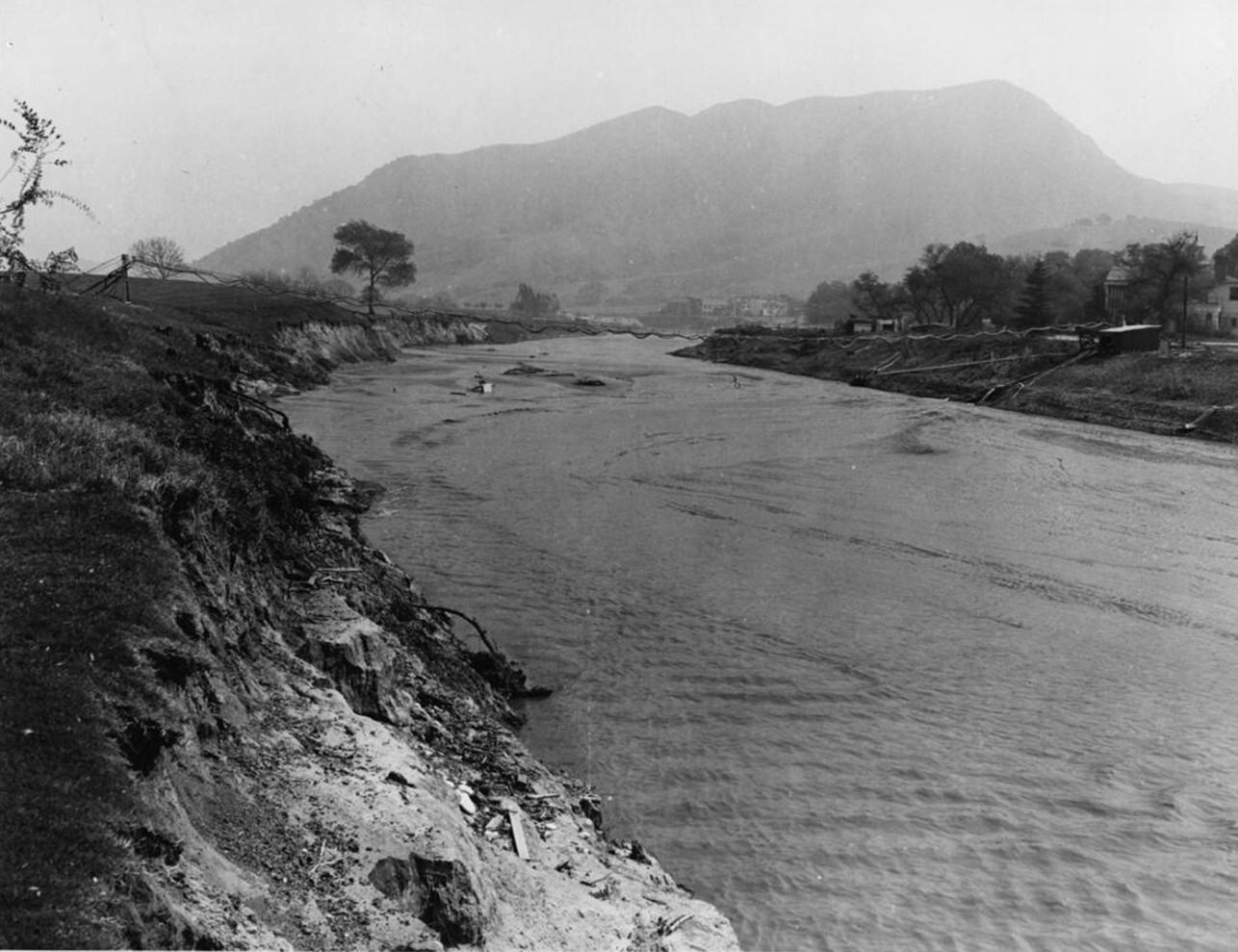

| (1932)* – View of the Los Angeles River looking north from Los Feliz. |

Historical Notes Originally a free-flowing alluvial river, the Los Angeles River shifted courses frequently. The flood of 1815 rerouted its waters through what is now downtown, flooding the original Plaza and forcing its relocation. Another major flood in 1825 returned the river to its present course and altered its outlet from Ballona Creek to San Pedro Bay. These floods drained marshes, destroyed sycamore forests, and even caused the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers to merge temporarily. For decades after, the river alternated between quiet periods and destructive floods, shaping settlement patterns and forcing residents to adapt to its power. |

|

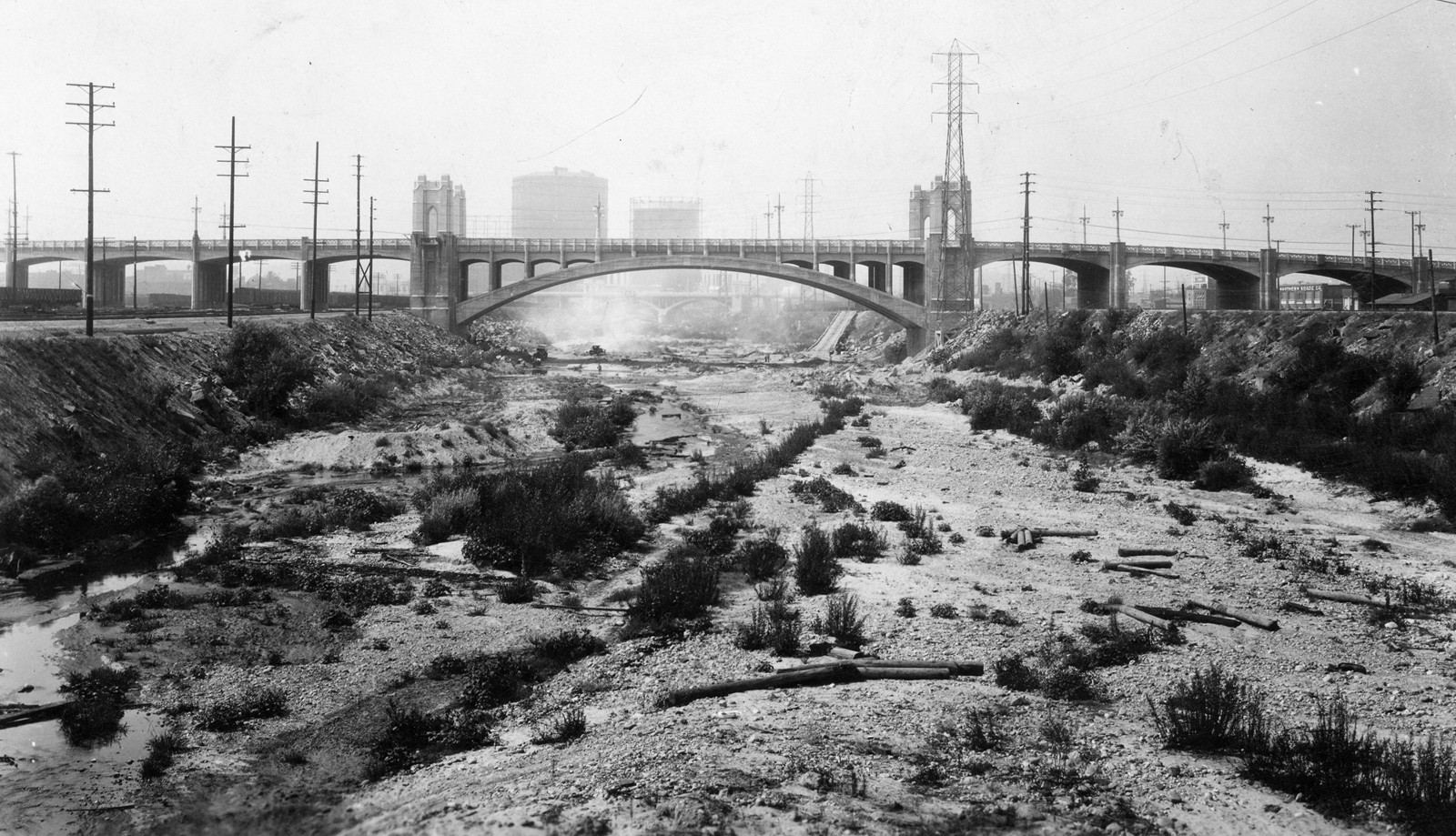

|

| (1931)* - View of a very dry Los Angeles River. The newly completed Fourth Street Bridge spans the unpaved channel before river channelization. Built at a cost of nearly $2 million, the bridge not only crossed the river but also rail lines and major roads, becoming one of the city’s great Depression-era landmarks. |

Historical Notes During drought years, the Los Angeles River often ran dry, exposing its sandy bottom. Early industries along the banks—including agriculture, tanneries, and later railroads—depended on its water but also dumped waste into it. By the early 20th century, the river’s unpredictability made it both an essential lifeline and a threat to the city’s expansion. |

|

|

| (1939)* - View of the Los Angeles River near downtown Los Angeles. In the background can be seen the large natural gas holders of the Southern California Gas Company, once prominent landmarks in the city’s industrial core. Photo by William Reagh |

Historical Notes In the late 1930s, much of the river near downtown remained unpaved, and the adjacent corridor was heavily industrial. The towering gas holders of the Southern California Gas Company dominated the skyline, reflecting a period when utility infrastructure was built on a monumental scale and often positioned near waterways for logistical convenience. Facilities like these underscored the importance of the river’s corridor as both a natural and industrial artery, even as the city moved toward encasing the river in concrete. |

* * * * * |

The 1938 Los Angeles Flood

|

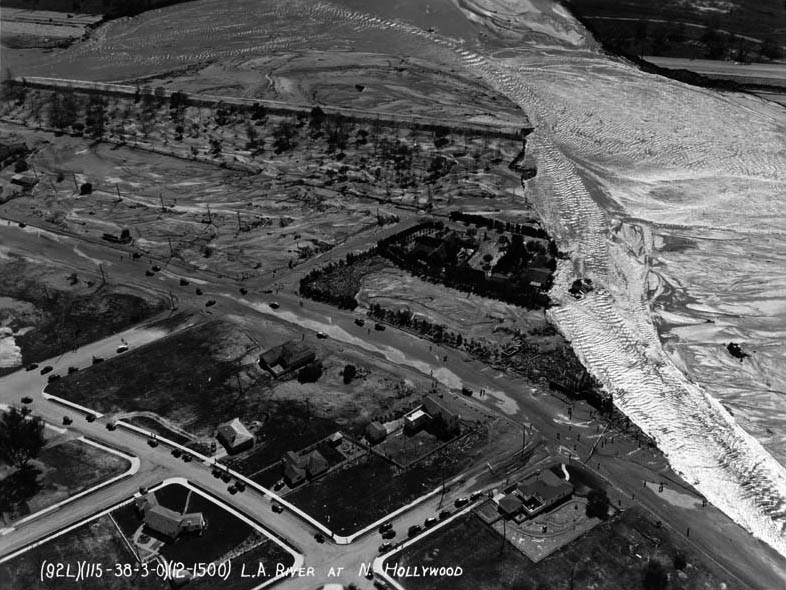

|

| (1938)* - Aerial photograph of the confluence of the Los Angeles River and the Central Branch Tujunga Wash, March 3, 1938, during the flood. Note both rivers spilling over their banks and a portion of Vineland Avenue washed away (lower left). |

Historical Notes There have been eight major floods in the San Fernando Valley since 1861, but the 1938 flood was one of the worst. Rain lasted for three days, breaking the Big Tujunga Wash levee and destroying 77 spreading basins. Warner Bros. studio buildings and the Olive Avenue Bridge were washed out. It took 30 days to clear storm debris, while utilities such as telephone and power were cut off. |

|

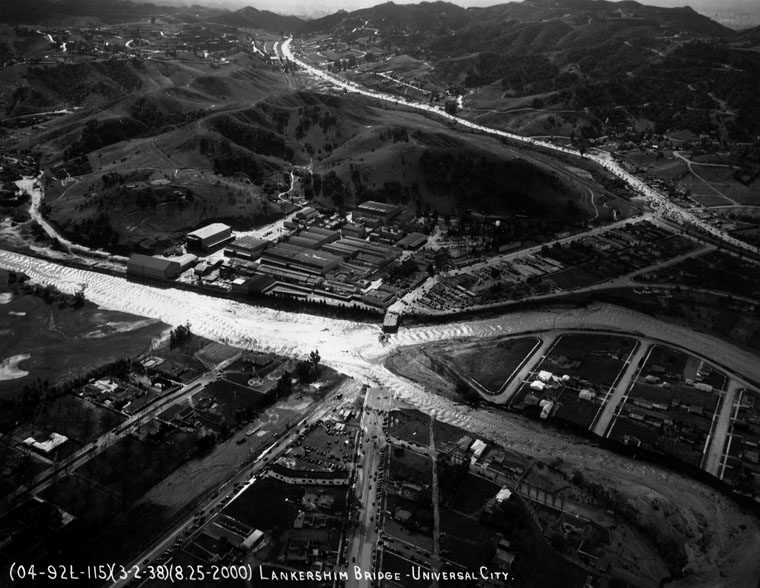

|

| (1938)* - Aerial view of the Lankershim Bridge in Universal City, destroyed by floodwaters. People gather at both ends to watch the raging river. |

Historical Notes From February 27 to March 1, a Pacific storm dropped 4.4 inches of rain on the lowlands and more than 32 inches in the mountains. A second storm on March 1 intensified the flooding. By March 3, the disaster had taken 115 lives. |

|

|

| (1938)* - Flooded area at Ventura Boulevard and Colfax Avenue in Studio City. Republic Studios is just out of frame to the left. |

Historical Notes The 1938 flood destroyed 5,601 homes and businesses and damaged another 1,500. Flooding was accompanied by debris flows of mud, trees, and boulders. Roads and railways were buried, power and communication lines severed, and dozens of bridges swept away. Some communities were buried under six feet of sediment. |

|

|

| (1938)* - Close-up view showing the washed-out bridge at Colfax Avenue over the Los Angeles River in Studio City. |

Historical Notes About 108,000 acres were flooded countywide. The San Fernando Valley was the worst-hit area, as many homes had been built on former floodplains during the 1920s boom. |

|

|

| (1938)* - Aerial view of devastation near the Los Angeles River overflow in the southwest portion of Glendale, where Glendale, Burbank, and Los Angeles meet. Riverside Drive runs from center-left to bottom-right; the street ending at the river is Western Avenue. Click HERE for contemporary aerial view. |

Historical Notes Many homes were located on old riverbeds that had not flooded in recent memory, leaving residents unprepared for the disaster. |

|

|

| (1938)* - Caption reads: "Flooding in Southern California killed dozens". This bus became stuck at 43rd Place near Leimert Boulevard. |

Historical Notes Swollen by tributaries, the Los Angeles River reached a flood stage of 99,000 cubic feet per second. The waters surged south, inundating Compton and Long Beach. A bridge at the river’s mouth collapsed, killing ten people. |

|

|

| (1938)* - People walk along a cement path that seems to have snapped in half as the dirt below the concrete washed away in the flooded Los Angeles River. |

Historical Notes Although the 1938 flood caused the greatest destruction in Los Angeles history, its rainfall totals and river flows were still less than the Great Flood of 1862. By 1938, however, Los Angeles was far more populated, magnifying the disaster’s impact. |

|

|

| (1938)* - View showing the Southern Pacific's first crossing washed out with two spans missing at the Dayton Avenue Bridge. |

Historical Notes Rail lines were severely disrupted, with bridges washed away and tracks buried under debris. |

|

|

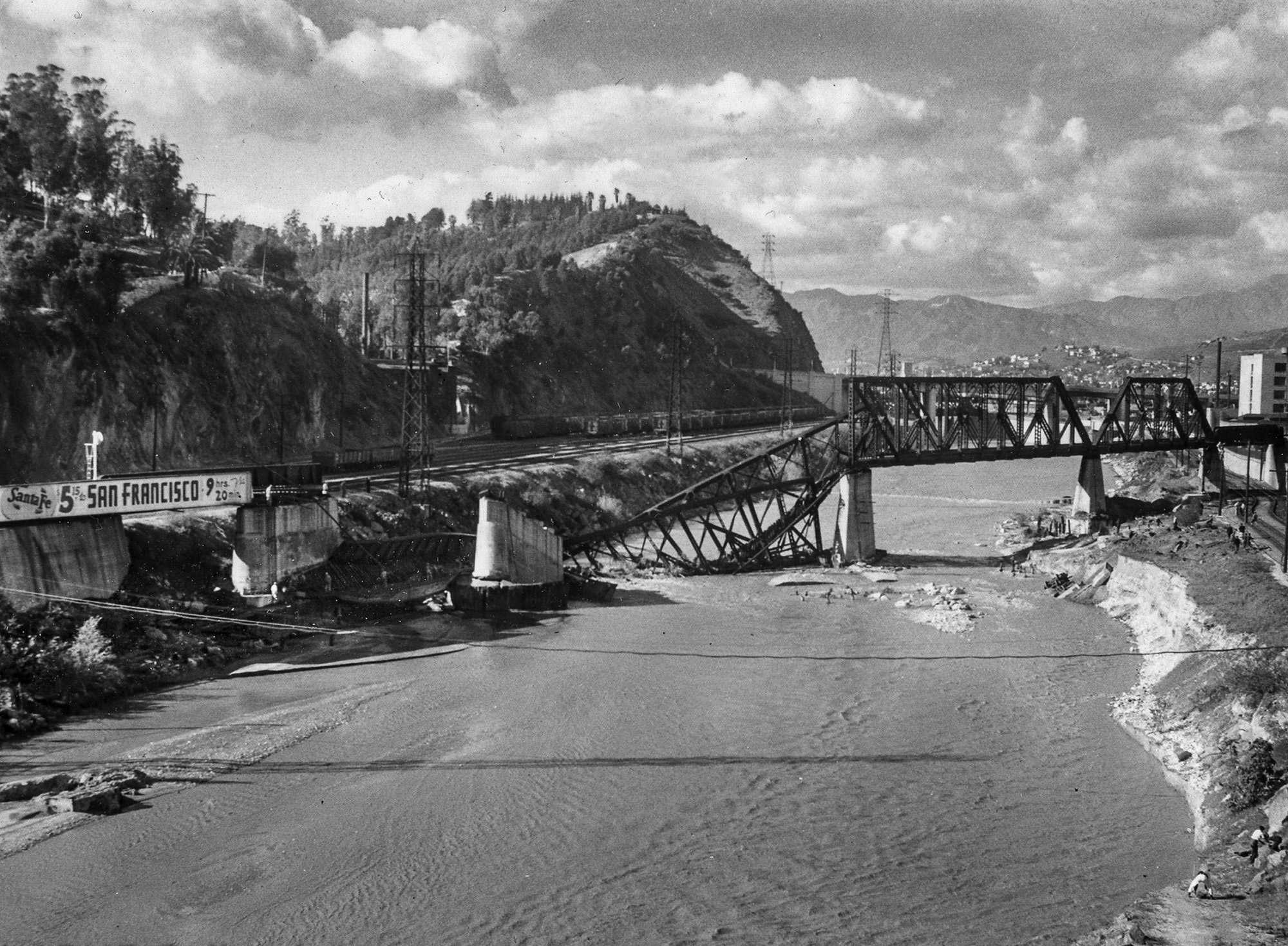

| (1941)* – Another major storm came in 1941 and the LA River was raging once again. It took out the truss bridge of Santa Fe's Pasadena Subdivision (then known as the Second District). Today this location is home to Metro's Gold Line between LA and Pasadena. |

Historical Notes The 1941 flood reinforced public demand for permanent river control, leading to the Army Corps of Engineers’ decades-long channelization project. |

* * * * * |

Channelization of the LA River

|

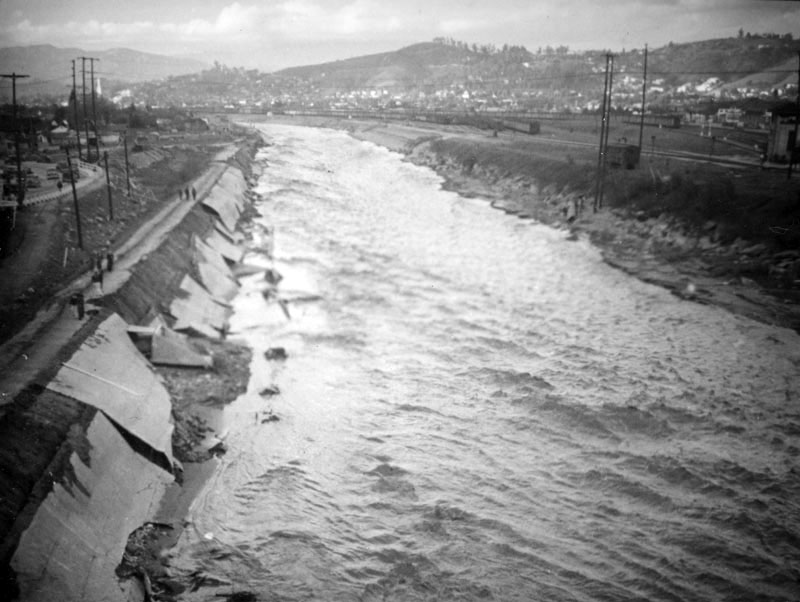

|

| (1938)* – Ground view showing embankment corrosion on the Los Angeles River in Studio City. |

Historical Notes After the great storm of 1938, due to public outcry, the Army Corps of Engineers began a 20 year project to create the permanent concrete channel which still contains most of the of riverbed today. They also installed a network of channels and flood basins to control the rampages of the waterways feeding the Los Angeles River. |

|

|

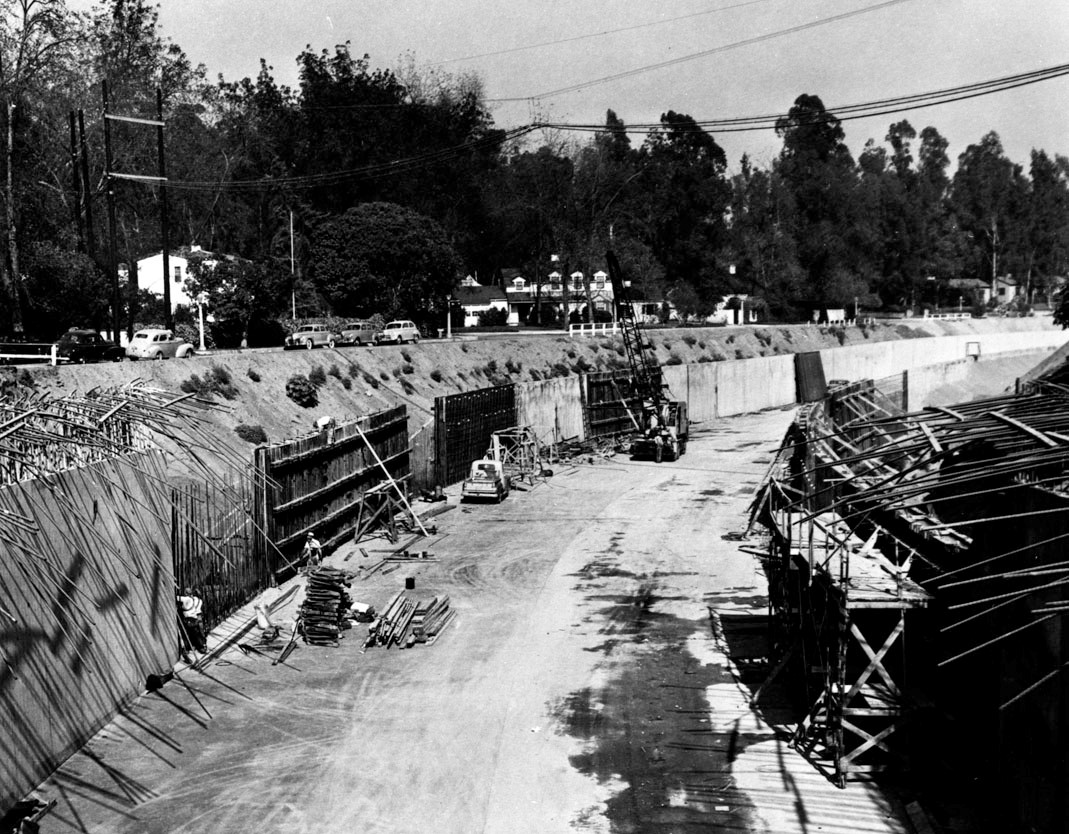

| (1949)* - View showing the construction of the channel walls in the Los Angeles River at Laurel Canyon in Studio City. |

Historical Notes Since 1938, 278 miles of river and tributaries were retrofitted and more than 300 bridges were built. With the river encased in cement, the natural sharp turns were now straightened. Any evidence of vegetation was completely removed, allowing runoff from the San Gabriel Mountains to escape through the river and out of Long Beach at up to 45 miles-per-hour. Streets and sewers were connected to drains along the river, designed to quickly capture and move rainfall away from the surrounding streets. |

|

|

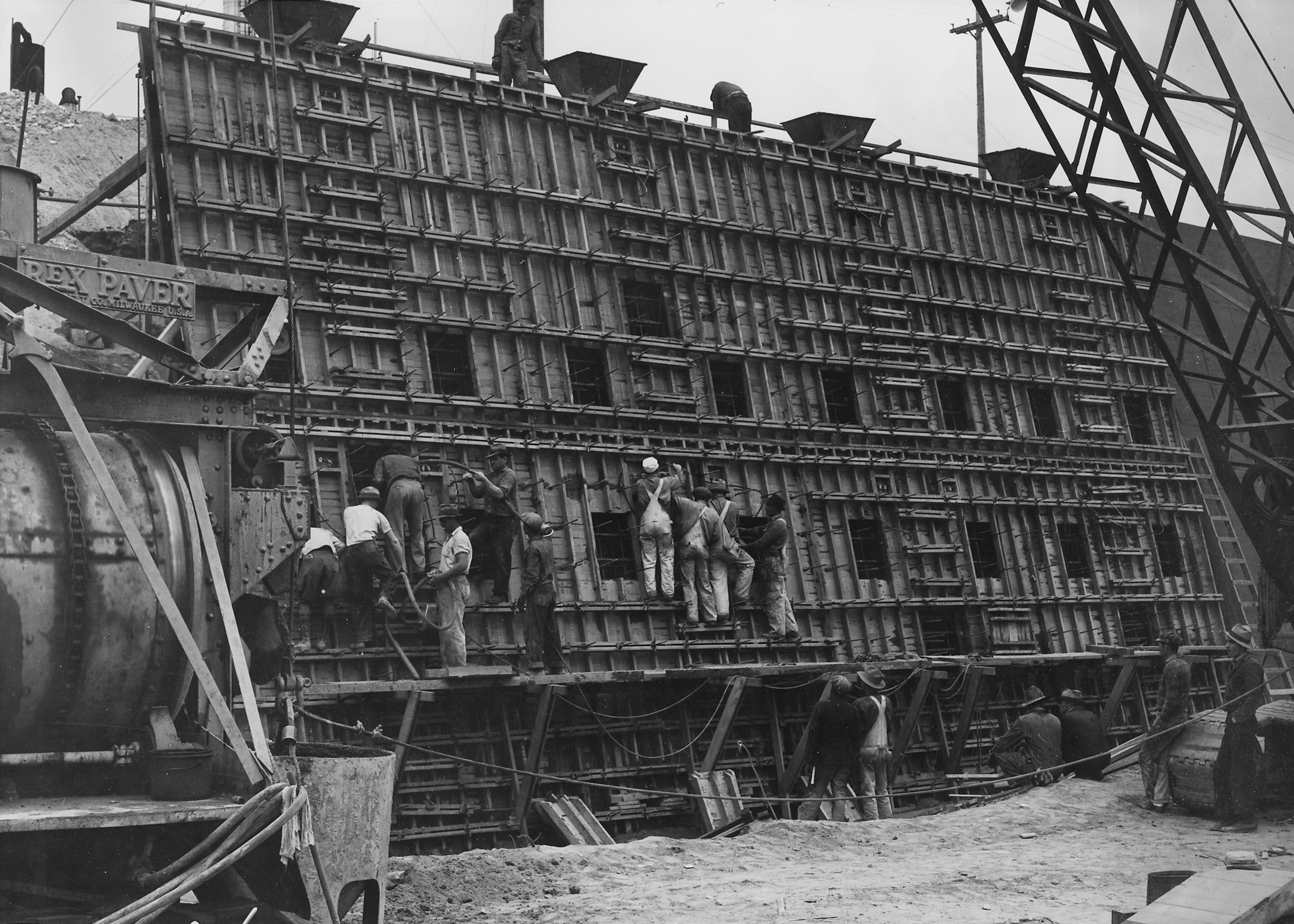

| (1938)*– Los Angeles River Channelization. View showing the placing of concrete in a section of the counterforted channel wall of the Los Angeles River. The men on the form are vibrating the concrete through windows which are progressively closed as the level of the concrete rises. |

Historical Notes The Corps’ standardized trapezoidal design—with sloping sides and a wide bottom—allowed for rapid drainage of floodwaters while making maintenance easier. |

Before and After

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

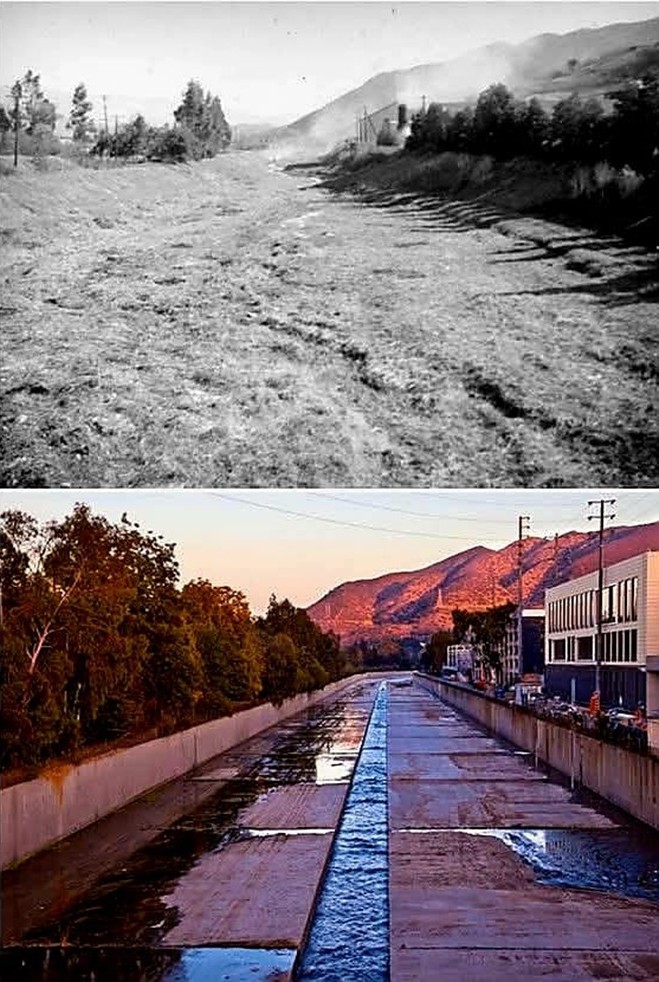

| (1937 vs. 2015)* - Before and After Los Angeles River Channelization in Studio City. |

Historical Notes The 1937 view shows the Los Angeles River as a wide, meandering waterway shaded by trees and flanked by open land. By 2015, the same location in Studio City had been converted into a straightened flood-control channel, with concrete replacing earth and vegetation. This transformation, carried out by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, reduced the flood risk for surrounding communities but erased much of the river’s natural character. The stark contrast captures the tension between safety and ecology, a theme that continues to shape discussions about river revitalization today. |

|

|

| (1937 vs. 2015)* - Before and After Los Angeles River Channelization in Studio City. |

* * * * * |

Before Cement Lining

|

|

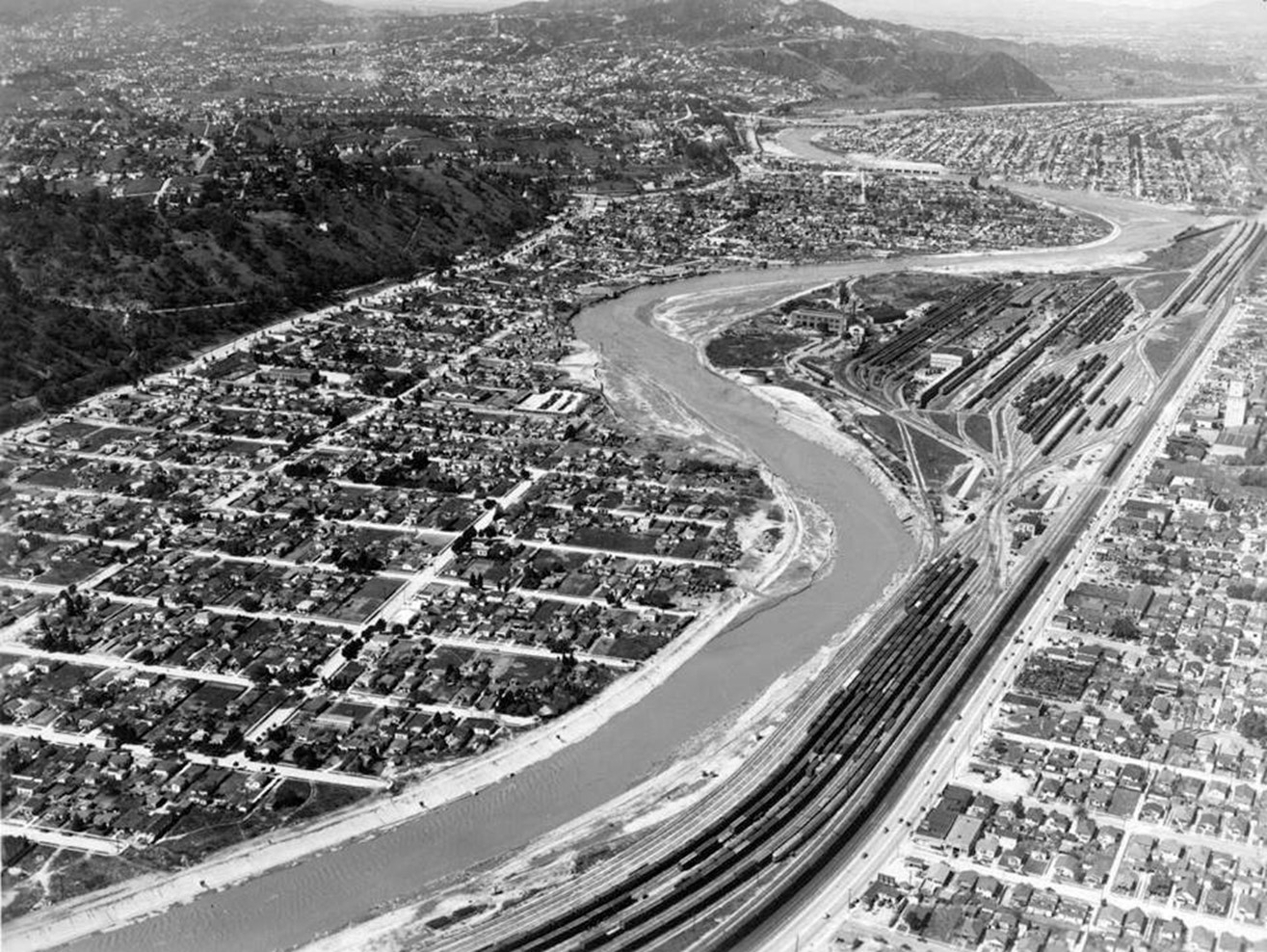

| (1940)* – View of a mostly unpaved L.A. River as it meanders through Elysian Valley (also known as Frogtown) with the Southern Pacific Railroad Yard (aka Taylor Yard) seen at center right. |

Historical Notes Before channelization, the Los Angeles River was a natural, meandering waterway. In the dry season it often appeared as a trickle, but during winter storms it could swell into a wide, unpredictable torrent. The soft-bottom river supported riparian habitat, with willows, sycamores, and wetlands providing shelter for wildlife. Yet its shifting course and seasonal flooding repeatedly threatened surrounding communities, setting the stage for the massive flood-control projects of the late 1930s and beyond. |

* * * * * |

After Cement Lining

|

|

| (ca. 1941)* - Image of the newly concrete-lined Los Angeles River looking north from Elysian Park, with houses, the Southern Pacific Railroad's Taylor Yard (across the river at right, with railroad train cars visible), the tower of the Great Mausoleum of Forest Lawn cemetery in Glendale (at center) and mountains in the distance. Photo by Bob Plunkett from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes This photograph captures the transition from a natural riverbed to an engineered flood-control channel. Taylor Yard, at right, was at the time a major Southern Pacific rail hub, linking Los Angeles to national markets. The prominent tower of Forest Lawn’s Great Mausoleum punctuates the horizon, while rows of modest houses line the river’s banks—evidence of how closely neighborhoods were built to the once-unpredictable waterway. The photo underscores the dual character of the river: an engineered solution to flooding, and at the same time a defining geographic feature around which communities, industry, and cultural landmarks developed. |

Then and Now (Elysian Valley)

|

|

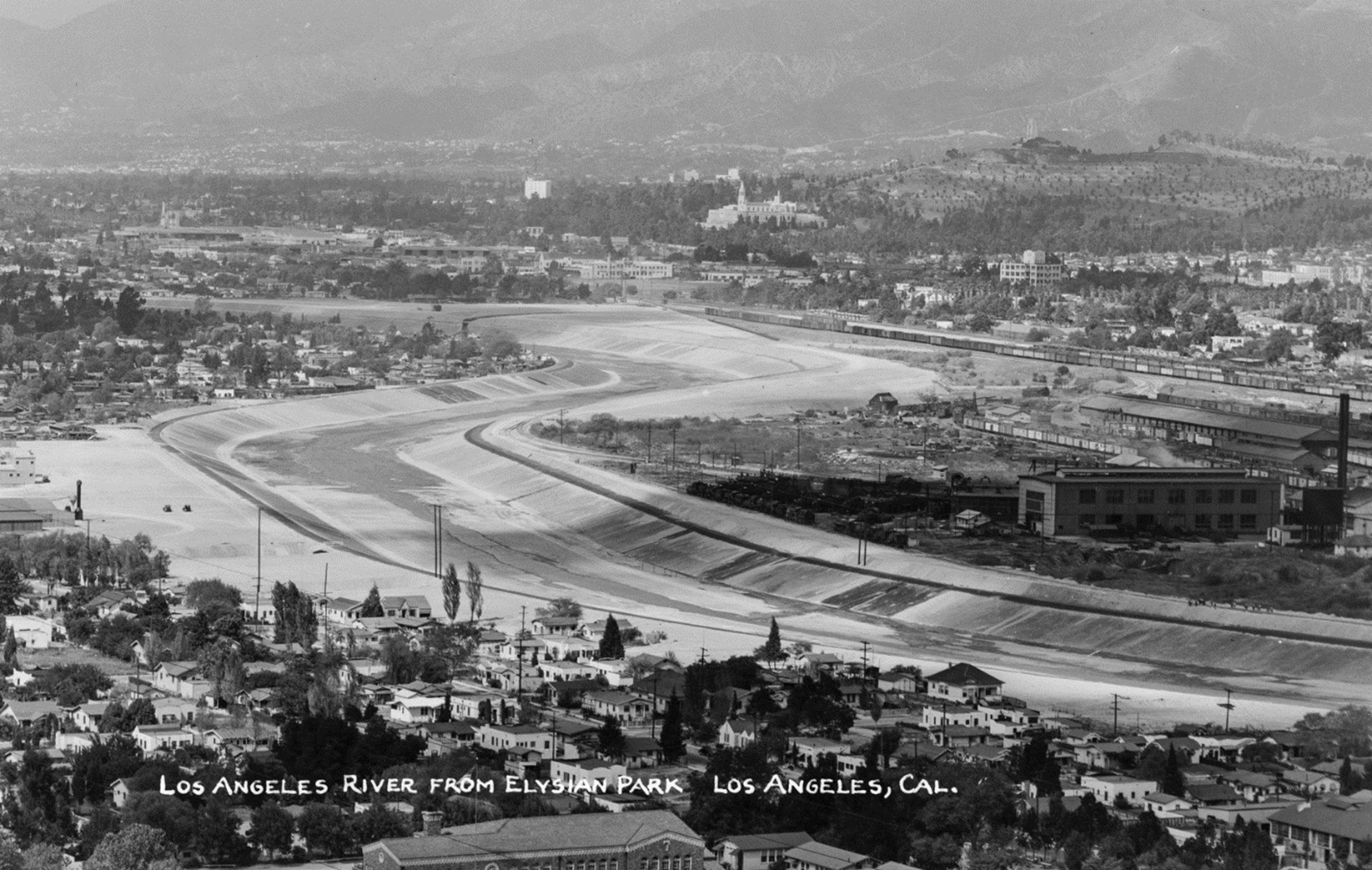

| (1940 vs 2023)* – A view of the Los Angeles River winding through Elysian Valley (also known as Frogtown), with the Southern Pacific Railroad Yard (formerly Taylor Yard) visible at center-right. Part of the former yard is now the Rio de Los Angeles State Park. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes In 1940, the Los Angeles River still retained sections of its natural bed as it wound past Elysian Valley and the Southern Pacific’s sprawling Taylor Yard rail facility. The riverbed was wide and unpaved, often reduced to a shallow stream in dry months but capable of overflowing during storms. By 2023, the scene has changed dramatically. The river here remains channelized, but much of Taylor Yard has been repurposed into the Rio de Los Angeles State Park, part of ongoing efforts to reclaim industrial land and reintroduce green space along the river. This “then and now” pairing illustrates both the loss of the river’s natural form and the city’s more recent attempts to reconnect communities with the waterway through parks, bike paths, and revitalization projects. |

Before and After (Glendale-Hyperion Bridge)

|

|

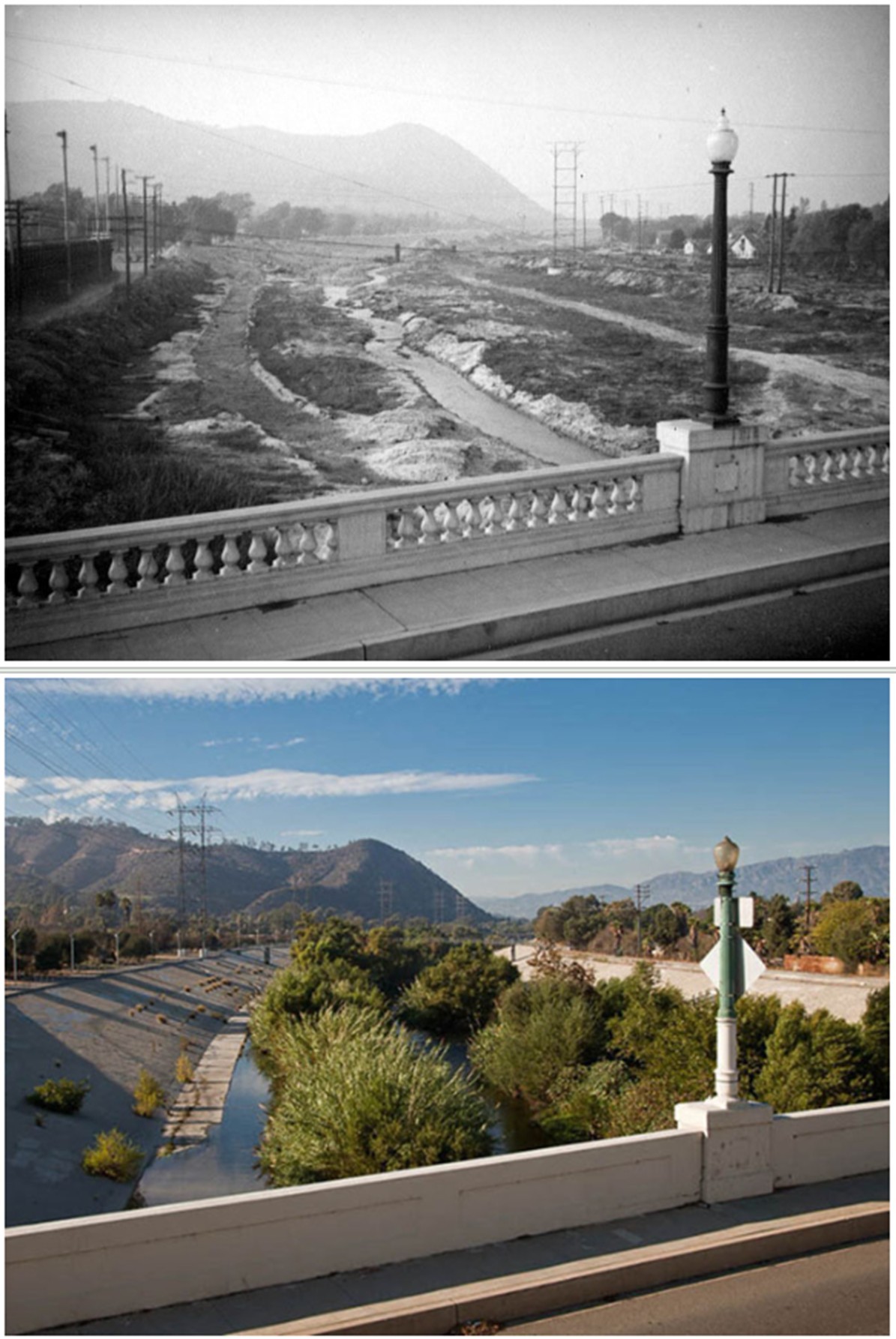

| (1937 vs. 2015)* - Los Angeles River Channelization from the Glendale-Hyperion Bridge. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman |

Historical Notes From the vantage of the Glendale-Hyperion Bridge, the 1937 view reveals a broad, natural channel filled with vegetation and capable of spreading widely during storms. The 2015 view shows the same stretch after decades of channelization—its floodplain replaced by concrete walls, roads, and development. While the channel has largely succeeded in containing floodwaters, it has also become emblematic of the city’s sacrifice of natural landscapes in favor of urban expansion. Unlike most of the river, however, this reach was left with a natural bottom so that stormwater could percolate into the ground and help recharge the San Fernando Valley aquifer. The bridge itself remains a link between eras, symbolizing continuity even as the river beneath it has been radically altered. |

Main Street Bridge

|

|

| (1949)* - Looking north from the Main Street bridge, water can be seen flowing in the Los Angeles river at the one-foot mark. (Herald Examiner Collection) |

Historical Notes The 1949 view from the Main Street Bridge captures the Los Angeles River just a few years after its full channelization in the wake of the catastrophic 1938 flood. By this time, the river through downtown had become a fully engineered flood-control corridor—its once-meandering course replaced by steep concrete banks designed to move stormwater swiftly toward the ocean. The water visible here at the one-foot gauge mark reflects the river’s typical dry-season condition, when flow was limited to a small ribbon fed primarily by treated wastewater, groundwater seepage, and storm-drain runoff. Industrial structures and rail lines along the channel walls underscore how tightly the downtown river corridor had become integrated with Los Angeles’s transportation and manufacturing infrastructure. Bridges like the one at Main Street were reinforced during this era to span the new, wider flood channel, and they served as vital connectors between the city’s historic core and the growing industrial districts to the east. This photo stands at a transitional moment—when the river was no longer a natural waterway yet had not yet become the focus of the revitalization efforts that define it today. |

Los Feliz Bridge

|

|

| (n.d.)* - View looking north showing the Los Feliz Boulevard Bridge over the Los Angeles River near Griffith Park. |

Historical Notes The good news is that the introduction of the new flood control channels and concrete lining has alleviated most, but not all, of the flooding problems of the past. The system successfully protected Los Angeles from massive flooding in 1969. |

|

|

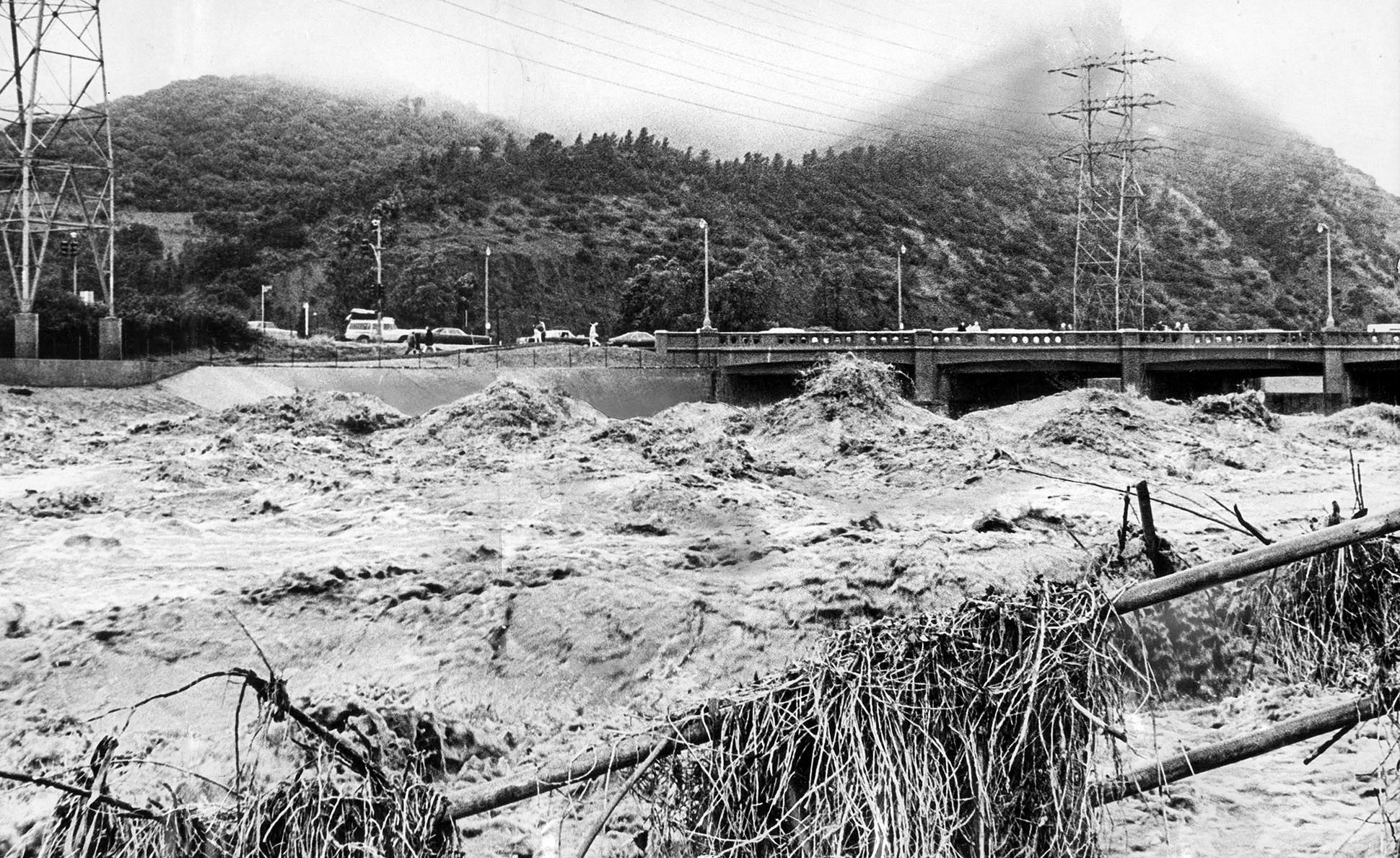

| (1969)* - Waves and rushing water fill the Los Angeles River at the Los Feliz Bridge during a storm that dropped over five inches of rain. Griffith Park is in the background. |

Historical Notes A Los Angeles Times article published on January 26, 1969 described the storm as “the worst floods in 31 years” and reported that a double-barreled system had continued for its eighth straight day, leaving at least 82 people dead, two missing, and causing more than $15 million in estimated property damage. Early reports noted that 34 people had been killed during the storm’s second phase alone, nine of them buried alive when mudslides swept into their homes. Authorities estimated that more than 6,000 residents had been evacuated as severe flooding affected communities from Fresno in the north to San Juan Capistrano in the south. These figures reflected preliminary reporting at the time. Later assessments by state and federal agencies placed the total death toll and overall damage significantly higher for the January 18–26 storm period, underscoring the severity of one of Southern California’s most destructive winter events since 1938. |

|

|

| (2000)* - Wide-angle view of the N. Broadway Bridge looking north shortly after it was retrofitted. The concrete-lined Los Angeles River is below as it appears throughout most of the year in semi-arid Southern California. |

Historical Notes The North Broadway Bridge underwent an 18-month, $20-million dollar renovation and seismic retrofitting that was completed in 2000. |

|

|

| (2013)* - View showing the Los Angeles River channelized with the 2nd Street Bridge seen in the background. Photo by Neil Kremer. |

Historical Notes By 2013, the Los Angeles River had long been confined within its concrete channel, a system designed in the wake of the devastating 1938 flood to prevent future disasters. This view near downtown shows the river as most Angelenos know it today—an engineered flood-control corridor running beneath city bridges. Though effective in protecting neighborhoods and infrastructure, the stark channel has also become a symbol of the city’s uneasy relationship with its natural waterway. In recent years, this stretch has been central to discussions about revitalization, with proposals to restore habitat, improve water quality, and create public spaces while still maintaining flood protection. |

Then and Now (Los Feliz Bridge)

|

|

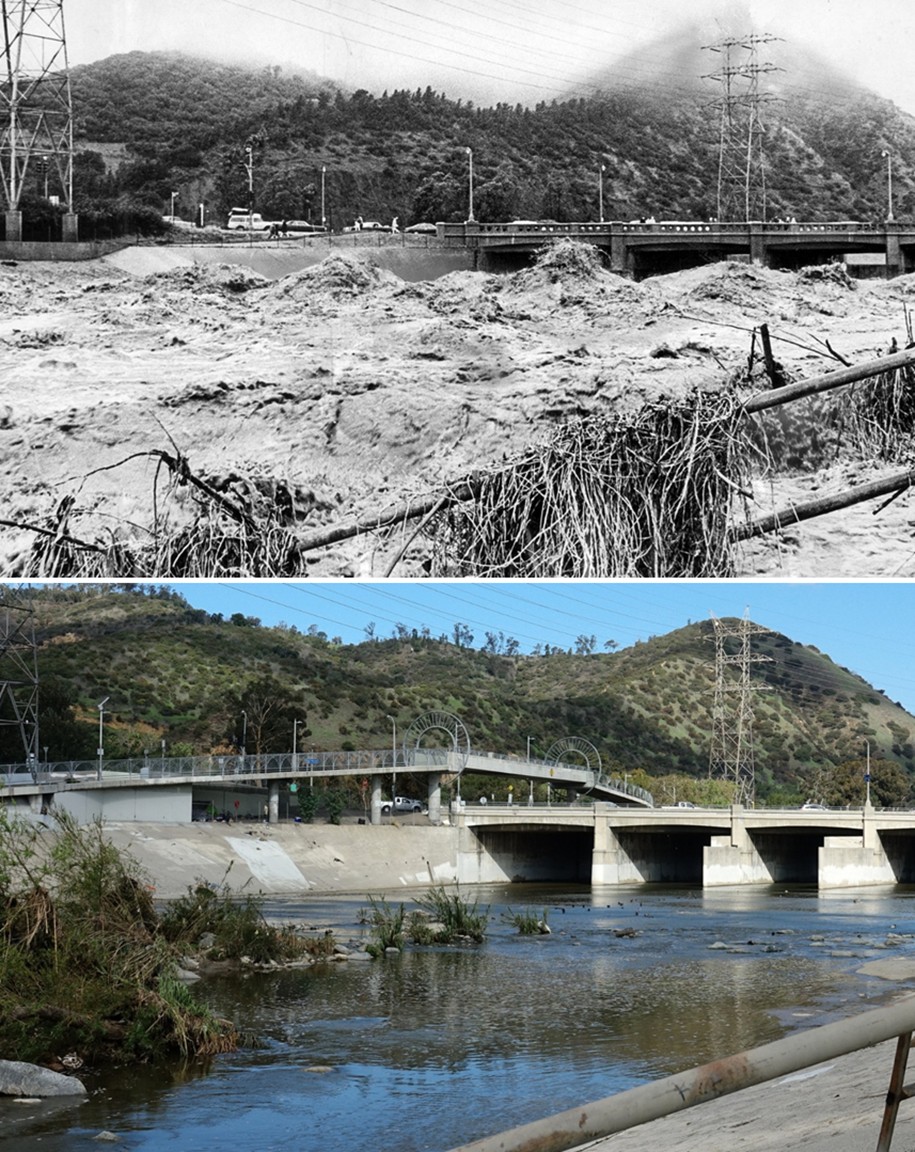

| (1969 vs 2023)* - Waves and rushing water fill the Los Angeles River at the Los Feliz Bridge during major storms with Griffith Park in the background. Bottom photo was taken by Don Williams on January 9, 2023 around midnight. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes The Los Feliz Bridge has long been a vantage point for witnessing the Los Angeles River at its most powerful. In 1969, a series of winter storms brought over five inches of rain in a week, producing the worst floods since 1938 and causing widespread damage across Southern California. More than 80 lives were lost and thousands were displaced. Over half a century later, the 2023 photo shows a similar scene as torrential rains again swelled the river, with water rushing nearly to the top of the channel walls. While the concrete lining has largely protected the city from catastrophic flooding since the mid-20th century, these images highlight the river’s enduring volatility and the challenges of balancing flood control with urban development and climate change–driven extremes. |

Then and Now (1969 vs 2018)

|

|

| (1969 vs 2018)* – Then and Now view of the Los Angeles River flowing beneath the Los Feliz Bridge during a major storm and under normal seasonal flow. Contemporary photo by Kevin Break. Photo comparison by Jack Feldman. |

Historical Notes The 1969 photograph captures the Los Angeles River at one of its most volatile moments, when a major winter storm sent a surge of muddy, debris-filled water rushing beneath the Los Feliz Bridge. That year's storms produced some of the region’s most destructive flooding since 1938, overwhelming storm channels and testing Los Angeles’s evolving flood-control system. The 2018 view, photographed by Kevin Break, shows the same location under normal seasonal flow, with the river running at the modest levels typical for much of the year. The modern bike and pedestrian bridge—added in the 2010s—now spans the channel just upstream, reflecting how the river corridor has continued to evolve. Seen together, these images highlight the dramatic contrast between the river’s calm appearance most days and the powerful force it becomes during major storms—a reminder of why the Los Angeles River was channelized and why flood management remains vital for Southern California. |

|

|

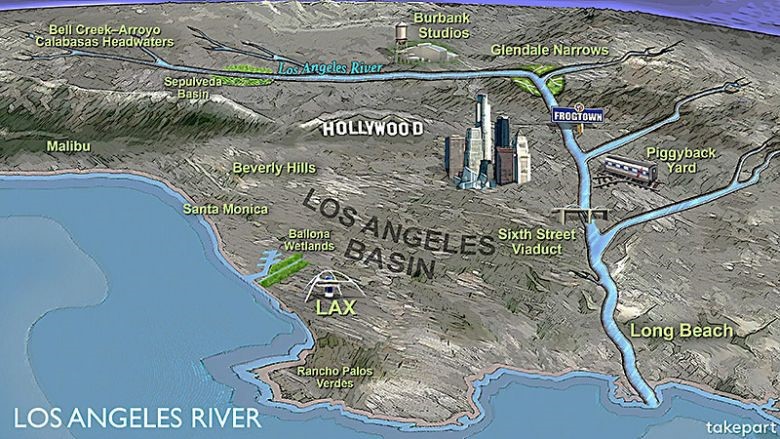

| Map showing the pathway of the Los Angeles River from its headwaters at the confluence of Bell Creek and Arroyo Calabasas to its outflow into the Pacific Ocean at Long Beach. Click HERE to see the headwaters of the Los Angeles River. Map illustration: Clark Kohanek* |

Historical Notes Today, the Los Angeles River stretches for about 60 miles from its headwaters in Canoga Park to its outlet in Long Beach Harbor. Though often seen as little more than a concrete flood channel, the river still plays a vital role in the region’s hydrology and identity. Along its length, it passes through diverse communities, industrial corridors, and green spaces, connecting the San Fernando Valley, downtown Los Angeles, and Gateway Cities before reaching the Pacific Ocean. In recent decades, renewed attention has been given to restoring portions of the river, reimagining it not just as a flood-control channel but as a civic and ecological asset. The map underscores how the river binds together much of Los Angeles County, both historically and in its future planning. |

* * * * * |

Please Support Our CauseWater and Power Associates, Inc. is a non-profit, public service organization dedicated to preserving historical records and photos. Your generosity allows us to continue to disseminate knowledge of the rich and diverse multicultural history of the greater Los Angeles area; to serve as a resource of historical information; and to assist in the preservation of the city's historic records.

|

History of Water and Electricity in Los Angeles

More Historical Early Views

Newest Additions

Early LA Buildings and City Views

* * * * * |

References and Credits

* LA Public Library Image Archive

^ CSUN Oviatt Library Digital Archives

^*KCET: LA Flood of 1938: Cement the River's Future

+^Wired.com: New Life for the LA River

*#The 1938 Los Angeles River Flood

#*California State Library Image Archive

+#Facebook.com: Photos of Los Angeles

#*Facebook.com: Los Angeles Railroad Heritage Foundation

#+Vintage Everyday: The 1938 Los Angeles Flood

#^Takepart.com: LA Remembers It Has a River

*+BridgeHunter.com: Los Feliz Blvd. Bridge

++Facebook.com: West San Fernando Valley Then And Now

+*You-are-here.com: Buena Vsta-Broadway Bridge

##LA Times: Historic Bridge to Downtown Reopens

+ US Corp of Engineers: The Los Angeles River

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Major Efforts

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Board Officers and Directors

- Mulholland/McCarthy Service Awards

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index