Water in Early Los Angeles

Introduction |

Los Angeles developed within a natural water system shaped by mountains, valleys, and gravity. Rain and snowmelt from surrounding ranges flowed into the San Fernando Valley, where water slowly collected and moved southeast toward the Los Angeles River. This natural pattern determined where water could be captured, stored, and shared long before modern engineering existed. |

The Natural Water Setting of Early Los Angeles

|

|

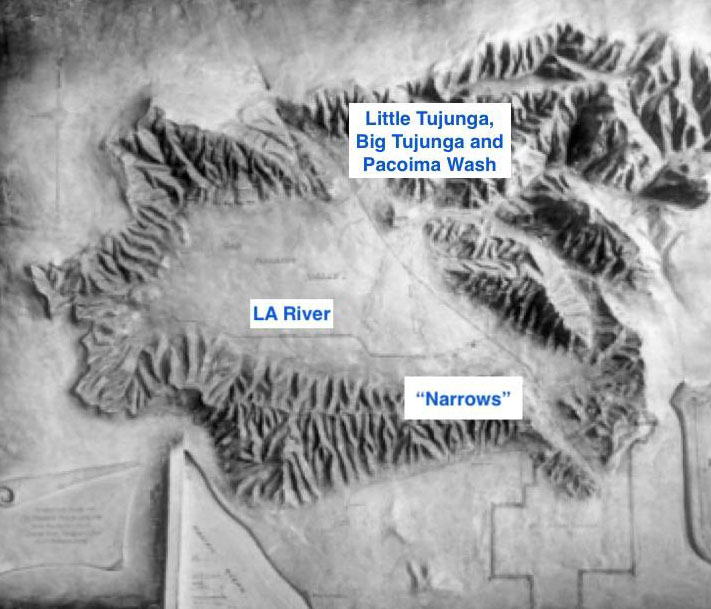

| Department of Water and Power raised-relief map of terrain in the San Fernando Valley showing the main source of water for the early inhabitants of Los Angeles. |

Historical Notes After the rise of the San Gabriel Mountains about 100 million years ago, and later the Simi Hills and the Santa Monica Mountains, water flowed through Little and Big Tujunga Canyons, the Pacoima Wash, and other surrounding canyons until a lake formed. As any avid skateboarder or bicyclist in the Valley can tell you, the Valley tilts from northwest to southeast and, as a result, the only exit for the water entering the Valley is through the Glendale Narrows (Narrows), as seen on the map. This is where the original water companies for Los Angeles were located before the Los Angeles Aqueduct. After the lake subsided, a huge watershed for the Los Angeles River was formed. In the late 1800s, Valley wheat farmers discovered they could drill down 25 to 50 feet in many spots and an artesian well would spring to life. |

* * * * * |

Water and Native Life Along the River

Long before European settlement, the Los Angeles River supported Native communities who depended on its seasonal flow for food, travel, and daily life. The river and its tributaries shaped where people lived and how they moved across the land. This long history of use set the foundation for later settlement patterns. |

|

|

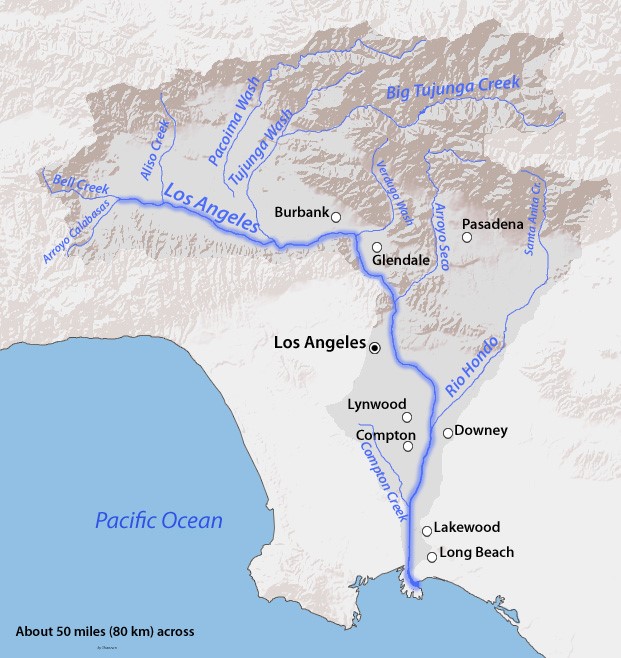

| USGS Map showing the full extent of the Los Angeles River and its tributaries.^ |

Historical Notes The river provided a source of water and food for the Tongva people prior to the arrival of the Spanish. After the establishment of Mission San Gabriel in 1771, the Spanish referred to all of the Tongva living in that mission's vicinity as Gabrieliño. The Tongva were hunters and gatherers who lived primarily off fish, small mammals, and the acorns from the abundant oak trees along the river's path. There were at least 45 Tongva villages located near the Los Angeles River, concentrated in the San Fernando Valley and the Elysian Valley, in what is present day Glendale. |

* * * * * |

The River and the Birth of the Pueblo

When Spanish explorers reached the Los Angeles River in the late 1700s, they immediately recognized its importance. The Pueblo de Los Angeles was founded nearby because the river offered a dependable water source in an otherwise dry landscape. From the beginning, the city’s survival depended on managing the river’s changing flow. |

|

|

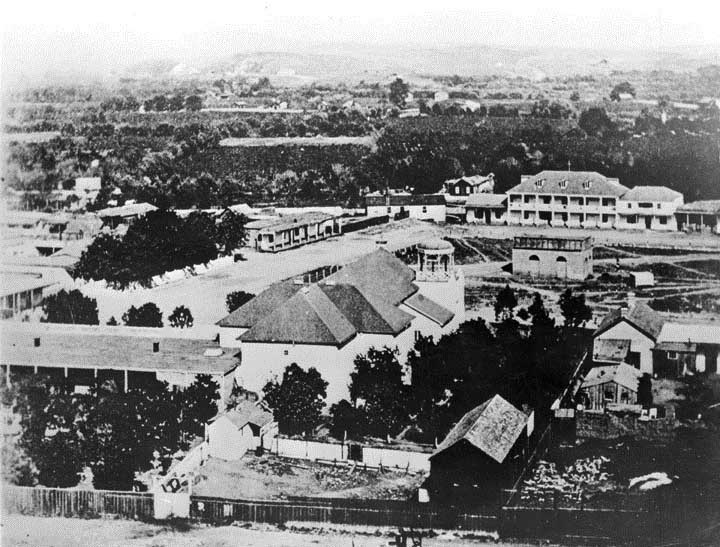

| (1850)* - This is an old photograph of an accurate model of Los Angeles as it appeared in 1850. Looking northeast, the layout of the new city can clearly be seen with the Los Angeles Plaza located in the lower left-center. The large white structure to the left of the Plaza is the Old Plaza Church. The Los Angeles River can be seen running from the lower-right diagonally to the center of the photo, turns left and disappears behind the mountain. At that point (near the "Narrows") the Arroyo Seco can be seen at its confluence with the Los Angeles River. The tall majestic San Gabriel Mountains stand in the far background. |

Historical Notes In 1769, members of the Portolá expedition to explore Alta California were the first Europeans to see the river. On August 2, the party camped near the river, somewhere along the stretch just to the north of the Interstate 10 crossing near downtown Los Angeles (lower-right in above photo). Fray Juan Crespi, one of two Franciscan missionaries traveling with Portolá, named it El Río de Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Ángeles de Porciúncula. Crespi chose that name, which translates as The River of Our Lady Queen of the Angels of Porciuncula, because it was the name of a special annual feast day for the Franciscans, which the Portolá party had celebrated the previous day. The river was thereafter referred to as the "Porciuncula River". In later years, the "Los Angeles" part of Crespi's lengthy name won out. |

* * * * * |

Early Water Engineering and the Zanja Madre

As the pueblo grew, carrying water by hand was no longer practical. Early water engineering focused on lifting river water into ditches that could carry it by gravity to homes, fields, and storage areas. The Zanja Madre became the city’s first organized water system and remained its lifeline for decades. |

|

|

| (1863)* - A 40-foot water wheel on the Los Angeles River at the start of the Zanja Madre, the city's original aqueduct. While often assumed to have lifted water with attached buckets, the wheel actually powered a pump that drew cleaner water from below the river’s surface. The river has been the life-source of Los Angeles since it was settled in 1781. |

Historical Notes The 40-foot water wheel seen above was used to raise a portion of the Los Angeles River's water supply to a height permitting gravity flow to homes, fields, and storage. Although it resembles traditional bucket-style wheels, this one actually powered a pump that drew cleaner water from below the surface of the river—avoiding the muddy surface flow—before feeding it into the Zanja Madre. In 1857, William Dryden was granted a franchise by the City Council to construct a system to provide a water supply. Under this system, a brick reservoir was built in the center of the Plaza to store the water brought by the Zanja Madre. The water wheel and pump combination lifted the water to the aqueduct, from which it was distributed to a number of houses along the principal streets through a system of wooden pipes. |

* * * * * |

Plaza Reservoirs and Early Storage

As Los Angeles expanded, storing water became just as important as moving it. Early reservoirs near the Plaza allowed the city to hold water for daily use, firefighting, and dry periods. These structures marked a key step toward a more reliable urban water supply. |

|

|

| (1869)* - View showing the LA Plaza with the Old Plaza Church on the left and the city's first above-ground water reservoir on the right. The square main brick reservoir was the terminus of the town's historic lifeline: The Zanja Madre. |

Historical Notes The old Pueblo de Los Angeles relied almost exclusively on the Los Angeles River for its water supply and thus its survival. In the early years water from the river was channeled through a distribution system of crude dams, water wheels and ditches. Los Angeles was incorporated as a municipality on April 4, 1850, but it wasn’t until ten years later that the City, through a lease contract with the LA Water Works Co., completed its first water system. After a succession of private water companies, the City formally took ownership of the first Los Angeles municipal water works system on Feb. 3, 1902. The City of Los Angeles faced a potential water shortage as early as 1900 due to two factors: an accelerated population growth and its unpredictable Los Angeles River. |

* * * * * |

Timeline: From Pueblo Ditches to a Municipal Water System (1781–1937) |

This timeline traces how Los Angeles gradually transformed its water system from a small pueblo reliant on open ditches and river access into a fully municipal utility serving a rapidly growing city. It highlights key moments when private companies attempted to control water delivery, the legal and political battles that followed, and the growing public demand for local ownership and reliability. Together, these events shaped the city’s decision to reclaim its water system and lay the groundwork for large-scale projects such as the Los Angeles Aqueduct. The entries below show how water policy, engineering, and governance evolved alongside Los Angeles itself. |

1781 - Pueblo de los Angeles is established on land adjacent to the Los Angeles River. The pueblo is invested with exclusive rights to the river water under Spanish colonial policy. River water is distributed by water carriers and later through a system of crude dams, water wheels and ditches. 1850 (April 4th) - Los Angeles is incorporated as a municipality, five months before California achieves statehood. 1853 - William G. Dryden makes a proposal to the City to construct a closed-pipe system to service homes. Water contamination was becoming a problem. The uncovered ditches are being polluted by bathers, animals, laundry use, and refuse disposal. However, the Los Angeles common council rejects Dryden's proposal because it believes his request for both land and a twenty-one-year franchise in return for the construction and operation of the system to be excessive. 1853 - Water carriers with jugs and wagons are allowed to serve the city's cleaner water needs and peddle higher quality water from door to door to augment the existing water courses. 1854 - The city council establishes a new position called Zanjero who is responsible for overseeing the protection of the water courses against blockage, contamination, breaches in the system, and illegal use of water by persons without authority. Click HERE to read more about the Zanjero. 1857 - The city council relents and agrees to grant Dryden a franchise to deliver water to homes through a system of wooden pipes beneath the streets. Dryden incorporates the Los Angeles Water Works Company. 1857 - LA Water Works erects a forty foot water wheel to lift water from the city's main ditch. 1858 - LA Water Works constructs a large brick and wood storage tank in the center of the city plaza (see below photo - 'LA's First Above-Ground Reservoir'). Click HERE to read more about William Dryden and the LA Waterworks Company. 1861 - Heavy rains washes out LA Water Works system. Dryden withdraws and closes up shop. 1863 - Jean L. Sainsevain enters into a similar contract with the city and promises to improve on Dryden's system but soon gives up. 1865 - The city leases what's left of the system to David W. Alexander who is unsuccessful at maintaining or improving the water system and gives up after only eight months. He reconveys his lease to Sainsevain. 1867 - Sainsevain with the assistance of former mayor Damien Marchessault erects a dam, builds a new water wheel and begins replacing wooden pipes with iron ones. 1868 - Severe flooding again destroys the water system. Sainsevain and Marchessault give up for good. 1868 - John S. Griffen, Solomon Lazard, and Prudent Beaudry, three of the city's more successful businessmen, submit a proposal to the city council to develop and operate the city's water system. In turn they ask for all of the city's water rights and control over the water rates. They also promise to construct a reservoir for the city, lay twelve miles of iron pipe, install fire hydrants at major street crossings, provide free water to public buildings, and to erect an ornamental fountain in the city plaza. 1868 - The city approves the franchise agreement on a 30 year lease basis. Griffen, Lazard, and Beaudry incorporate as the Los Angeles City Water Company. 1868 - LA City Water Company begins to buy out most of the private sources of water supply within the city as well as private companies which service areas outside the city limits. Over the next three decades only one smaller company, West LA Water Company, would survive LA City Water Co.’s takeover bid. Click HERE to read more about LA's Early Water Works System. 1878 - Fred Eaton, Superintendent of the LA City Water Company, hires William Mulholland as a ditch digger. 1868 - 1898 LA City Water Company violates the lease agreement on numerous occasions. There is on-going litigation between the City and the water company and at times requiring resolution at the level of the California Supreme Court. The relationship between the City and the water company stays contentious over a 30 year period due to repeated lease violations, high water rates, and poor system reliability. Toward the end of the lease, there is growing popular support for returning to complete municipal control of water system. 1889 - Amendments are made to the city charter affirming the city's authority to operate its own system. The charter is also changed to prohibit the city from entering into new leases that could not be canceled on six months’ notice. 1896 - In the local elections both political parties strongly advocate for the termination of the current lease with the private water company and for the creation of a municipally run waterworks system. 1897 - The city council directs the city engineer to begin drawing up plans for a municipal waterworks system. The city also gives notice to the LA City Water Co. that their lease would not be renewed after it expires on July 21, 1898. 1898 - The city opens negotiations with LA City Water Co. for acquisition of its water system. 1898 - Fred Eaton is elected mayor of Los Angeles. He ran for office on the platform of establishing a new municipal water system for the City of Los Angeles. 1899 - A $2.09 million bond measure for the purchase of LA City Water Co.’s system is approved by city voters by a margin of nearly eight to one. 1899 - LA City Water Co. responds with litigations which drags the takeover process for almost four years past the expiration date of the lease. 1902 (February 13) The City of Los Angeles regains control of its water system. A new department is created, Los Angeles Water Department. 1902 - William Mulholland is selected as superintendent of the new municipal water system. He brings with him the more senior employees from his previous employer, the LA Water Co., since the City has no ability to run the newly acquired waterworks system. 1902 - By ordinance, the city council establishes a new seven-member Board of Water Commissioners. Board members are elected to two-year terms. The city council retains the authority to make all appropriations from the water system revenues. It also has the authority to set the water rates. This arrangement is quickly discarded because it left the management of the system almost completely exposed to the changing whims of the electorate. 1903 -The city charter is amended to establish a reconstituted five-member Board of Water Commissioners. All five members are to be appointed by the mayor, subject to confirmation by the city council. The Board would have autonomous authority over the finances and operations of the new municipal water system. The setting of the rates would still need approval by the city council. The water system's revenues were to be placed in a special account over which the commission exercised exclusive authority, subject only to the council’s power to set aside certain funds for the payment of principal and interest on outstanding bonds. There would also be a general prohibition on expenditures for anything not necessary to the operation of the water system. 1903 - As a direct result of its experience with the LA City Water Co., the city charter is amended to prohibit the sale, lease, or other disposition of any water or water right “now or hereafter owned or controlled by the city” without the consent of two-thirds of Los Angeles’ voters. 1903 - Once the new city water organization is set up, it reduces the metered water rates by 50% to ten cents per thousand gallons. At this time water rates in San Francisco is 24 cents per thousand gallons, 40 cents in Oakland, and 30 cents in Alameda. The City also expands the use of water meters which has the immediate effect of dropping consumption by a third. 1903 - Mulholland completes the Elysian Reservoir, expands the Buena Vista pumping plant, and buys out the West Los Angeles Water Company, the sole survivor of the LA City Water Co.'s attempt to entirely capture the market during their 30 years of franchise. 1903 - William Mulholland and Ex-Mayor Fred Eaton look to the north with a plan to tap into the Owens River and bring water down to a fast-growing Los Angeles. 1904 - Eaton and Mulholland travel to see the Owens Valley first hand. Mulholland is convinced of the feasibility to construct an aqueduct between Owens Valley and Los Angeles. 1904 - Eaton, with the help of his friend and local chief of the Reclamation Service J.B. Lippincott, begin buying up land in the Owens Valley. 1905 - Fred Eaton returns from a trip to the Owens Valley after purchasing all the land and water rights that would make an aqueduct possible. He announces his plan to divert part of the Owens River water flow to Los Angeles. The event is printed in the local newspaper (To read the account in the original newspaper article click one of the following links: Los Angeles Times or Los Angeles Express ). 1906 - The Board of Water Commissioners votes to undertake the Los Angeles Aqueduct Project on the recommendation of William Mulholland. The Board decides to use its own resources to purchase Fred Eaton's land and water rights options. 1906 - A $1.5 million bond issue is approved by City voters on a more than 10 to 1 margin to proceed with a feasibility study for the construction of a new aqueduct. 1906 - The Board of Water Commissioners creates the Bureau of Los Angeles Aqueduct. They appoint William Mulholland as Chief Engineer. 1906 (June 25th) - President Theodore Roosevelt signs into law a Congressional bill giving Los Angeles the water rights to Owens River water. 1907 - Los Angeles voters unanimously approve a $23 million bond issue for the aqueduct's construction. 1908 - The Bureau of Los Angeles Aqueduct begins construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct to bring Owens River water 233-miles south to Los Angeles. 1911 - The city charter is amended to create the Department of Public Service, consisting of two bureaus, the Bureau of Water Works and Supply and the Bureau of Power and Light. William Mulholland is named chief engineer of the former and E. F. Scattergood of the latter. 1911 - The Water Department is renamed the Bureau of Water Works and Supply. 1913 - The Los Angeles Aqueduct is completed and the City has a new source of water. LA proceeds to annex outlying communities attracted by the promise of an abundant water supply. The flurry of annexations begins even before the aqueduct is complete. Click HERE to read more in Construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. 1910 - 1930, The area of Los Angeles increases from 115 sq. miles to 442 sq. miles through annexations of surrounding areas (i.e. Hollywood is annexed in 1910, the San Fernando Valley is annexed in 1915). The City's population increases from 533,535 (1915) to 1,300,000 (1930). 1914 - 1924, 32 private water utilities operating in the perimeter of the growing municipality of Los Angeles are taken over by the Bureau of Water Works and Supply. 1937 - The Bureau of Water Works and Supply consolidates with the Bureau of Power and Light and becomes the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). Notes After 1947, through a Los Angeles City charter change, City voter approval is no longer required for the DWP to issue bonds. |

* * * * * |

Evolution of LA's Water Service Providers

|

|

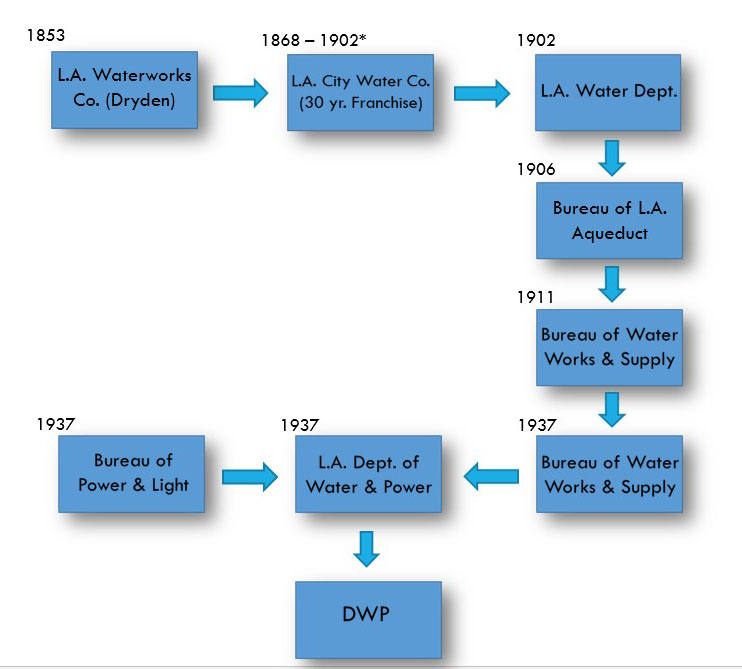

| Flow chart showing the evolution of water companies serving Los Angeles since 1853. Also shown are the various name changes the municipal utility (now DWP) has gone through since it was created in 1902. |

Historical Notes The Los Angeles City Water Company had a 30 year franchise lease that should have expired in 1898. However, the private company took the City to court and it took another 4 years (1902) before the City could take back the franchise and start its own municipal utility. |

* * * * * |

LA's First Above-Ground Water Reservoir

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1860)* - Los Angeles Reservoir - One of Los Angeles’ first water reservoirs was the brick structure shown in the center of the Plaza. The street extending to the left is Wine Street (renamed Olvera Street). The three-story building in the background was the Sisters of Charity Orphanage, established in 1856. The reservoir was built in 1858 by William G. Dryden and his Los Angeles Water Works Company. |

Historical Notes Click HERE to read more about LA's Early Water Works System. |

|

|

| (1865)* - The Plaza, looking east, with LA's first reservoir to the right of the picture. Click HERE to see more early photos of the Los Angeles Plaza and LA's first reservoir. |

* * * * * |

Expanding the System Beyond the Plaza

By the late 1800s, Los Angeles was spreading beyond its original center. New neighborhoods required new sources of storage and pumping. Reservoirs and pumping stations were built farther from the river, reflecting the city’s transition from a compact pueblo to a growing urban area. |

Buena Vista Reservoir

.jpg) |

|

| (1876)* - Buena Vista Reservoir - As the desire for more storage arose, and the wooden pipes were being replaced by miles of iron pipe, the Buena Vista Reservoir was created in 1868-9 using a small earthen dam and built at an elevation of 378 feet. It was built by privately owned L.A. Water Company and was its first storage facility. The photo shows the reservoir as seen from the hills, looking east from the present-day location of the Pasadena Freeway. |

.jpg) |

|

| (1876)* - Buena Vista Reservoir - The photo above shows a bridge over the Buena Vista Reservoir in Elysian Park. In 1880, working for the LA Water Company, William Mulholland was put in charge of enlarging the Buena Vista Reservoir from three to thirteen-million gallon capacity. |

Historical Notes Click HERE to see more of LA's Early Water Reservoirs. |

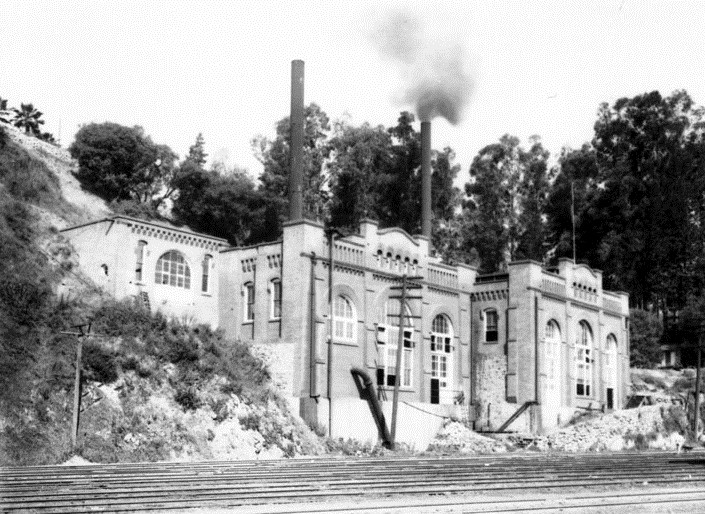

Buena Vista Pumping Station

|

|

| Buena Vista Pumping Station was located at the edge of Elysian Park, east of the North Figueroa Street Bridge, and faced the Los Angeles River. It was placed in operation by the Water Bureau in 1904. The original plant replaced a water wheel, located in the near vicinity. It pumped water from Buena Vista to Solano and Highland Reservoirs.* |

Historical Notes One of the first installations, the Buena Vista Pumping Station consisted of a vertical shaft, 14-ft in diameter, which connected with a tunnel which ran to about the present site of the Lincoln Heights City jail (1939). The tunnel tapped water from infiltration galleries, carrying it by gravity flow to the shaft. Water was lifted by a big pump, submerged at the bottom of the shaft and operated by rods driven by a steam engine. |

|

|

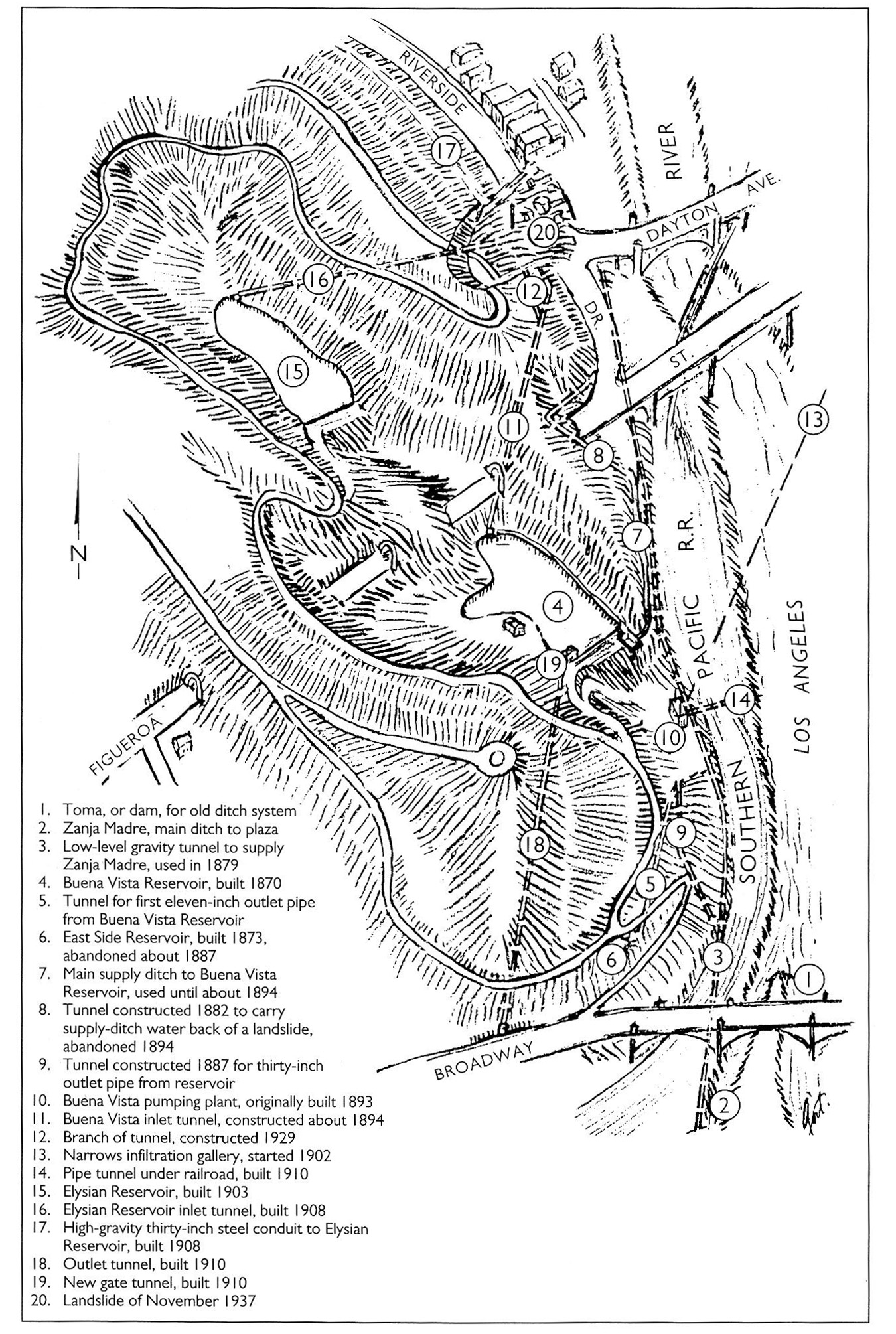

| (1938)*^ - Map of the Elysian Park area showing waterworks structures dating from Zanja Madre days to 1937. |

* * * * * |

The Los Angeles River in Daily Use

Throughout the 19th century, the Los Angeles River remained an open and working landscape. Water was diverted through small gates and ditches, shared among nearby users, and adapted to seasonal changes. These views show the river as an active part of everyday life rather than a fixed channel. |

The Los Angeles River

|

|

| (ca. 1895-1898)^^ – View of 2 men standing near a water ditch at the bank of the Los Angeles River, north side of Griffith Park. One man leans against a shovel. Horses are visible in the background. Trees are behind the man with the shovel (at right). In the foreground are relatively still waters and cattails.; Originally, the record was entitled as "Los Angeles River headwaters in Griffith Park". The Los Angeles River's headwaters, however, are farther NW in the San Fernando Valley, CA. |

|

|

| (ca. 1900)^^ - View of a man standing near a water ditch at the bank of Los Angeles River, north side of Griffith Park. The ditch (full of water) has been dug at left. A stand of trees is beside the relatively still water. This is the same view as previous photo but a couple of years later. |

|

|

| (1898)^^ - A man is seen by a water ditch gate at the bank of the Los Angeles River at the present-day site of Griffith Park. |

Historical Notes Click HERE to see " Los Angeles River - The Unpredictable!" |

* * * * * |

Zanjas in the Growing City

Zanjas ran alongside streets, crossed sidewalks, and passed directly in front of homes. They supplied water for households, gardens, livestock, and small industries. As Los Angeles grew, these open channels became harder to maintain, but they remained essential well into the early 20th century. |

.jpg) |

|

| (1890)* – View looking northwest showing an unpaved Figueroa Street. Note the water-filled ditch (Zanja) on the west side of Figueroa with walkway crossings in front of each of the large homes. A two-story Victorian-style house is visible to the left, followed further to the right by a one-story clapboard-sided home with a porch, to the left of which a windmill is situated. |

Historical Notes From its founding in 1781 through the early 20th century, Los Angeles relied on a network of open water channels, or zanjas, to distribute water for both domestic and agricultural use. These ditches operated under Spanish, Mexican, and later U.S. governance, providing a flexible and locally managed water system. In 1864, the city introduced pressurized water mains, but zanjas remained in use for another 40 years, offering users greater control over sourcing and distribution. While the mains provided reliable, pressurized water delivery, the zanjas allowed for more adaptable use. |

|

|

| (1890)* – Looking south on Figueroa Street, showing Zanja 8-R running between the sidewalk and the residential property line. Photo by C. C. Pierce. |

Historical Notes The development of Los Angeles' water infrastructure was shaped by lawsuits, regulations, and system modifications. Throughout the 1880s, the zanja network expanded to serve new areas as urbanization pushed agriculture southward. The city's first major population boom, fueled by the arrival of the Santa Fe Railroad in the mid-1880s, further transformed water needs. The Zanjero, a public official, oversaw water distribution and resolved conflicts over irrigation, laundry, and sanitation. Over time, urbanization led to covering zanjas for convenience, drainage, and water quality concerns. Some were even converted into storm drains. |

|

|

| (ca. 1900)* – View of the Charles H. Capen residence at 818 West Adams Street, a three-story Queen Anne-style house on a spacious lot, surrounded by young trees, shrubs, and pepper trees lining the sidewalk. A cement-lined ditch at the lawn's edge, known as the Zanja (Spanish for 'ditch'), served as the original water supply for the city's southwest. Built in 1868 and reconstructed in concrete in 1885, it was part of a network of 10 zanjas that, by the 1880s, extended 93 miles. Photo from the Ernest Marquez Collection. |

Historical Notes By the late 19th century, pollution from the booming oil industry became a significant issue, contaminating irrigation water and damaging crops and property. In response to public complaints, the city imposed regulations, restricted drilling near Westlake (now MacArthur) Park, and altered drainage routes. However, as the oil industry expanded, lawmakers often dismissed pollution concerns as unavoidable. Meanwhile, manufactured gas production introduced even more severe water contamination, with industrial waste draining into the zanjas. Legal battles followed, but courts often sided with industry, treating environmental damage as a necessary consequence of economic progress. |

|

|

| (1890s)* – View looking north showing the Stimson House at 2421 South Figueroa Street, with a water ditch (zanja) running parallel to Figueroa along the property line. |

Historical Notes Zanjas were multipurpose, sometimes carrying both water and waste. As sanitary sewers developed, they became more independent of zanjas, though some zanja water was still used for flushing sewage lines. Despite growing concerns over contamination, many Angelenos continued to rely on zanjas for domestic and industrial use, choosing water sources based on cost, availability, and perceived quality. As public health theories shifted from miasma concerns to germ theory, officials placed greater emphasis on clean water and filtration. |

|

|

| (2024)* – Google Street View showing the walkway crossing over remnants of the zanja in front of the gate to Mt. St. Mary’s University on Figueroa, just south of the Stimson House. |

Historical Notes William Mulholland’s 1903 Water Supply Report marked the beginning of the end for Los Angeles’ zanjas, declaring them economically unsustainable due to high maintenance costs, excessive water loss, and mounting legal liabilities from contamination lawsuits. The open-air canals, which had served the city for over a century, lost favor as Mulholland prioritized a more efficient, centralized water distribution system. His 1904 Reallocation Order further sealed their fate by diverting nearly all Los Angeles River flows into underground mains, reducing irrigation deliveries by 95%. |

|

|

| (2024)* – Closer view of the walkway crossing over remnants of the zanja in front of the gate to Mt. St. Mary’s University on Figueroa, just south of the Stimson House. |

Historical Notes In 1904, William Mulholland shut down the zanjas to consolidate the water supply into the pressurized mains, reducing local control and adaptability. By 1907, Los Angeles had fully phased out zanja water, marking a shift from a decentralized system to a centralized, commodified one. While modern histories often highlight large-scale projects like the Los Angeles Aqueduct (1913), this earlier period reveals a complex, user-driven water system that played a crucial role in shaping the city's development. |

|

|

| (2024)* – Close-up sidewalk view of the walkway crossing over remnants of the zanja in front of the gate to Mt. St. Mary’s University on Figueroa, just south of the Stimson House. Photo courtesy of Gary Helsinger. |

Historical Notes William Mulholland’s 1903 Water Supply Report sealed the zanjas’ fate by declaring them “economically unsustainable” due to several key factors: annual maintenance costs of $18,000 compared to only $12,000 in revenue, a 43% water loss compared to just 9% for the mains, and legal liability from 22 pending contamination lawsuits. Mulholland’s 1904 Reallocation Order diverted Los Angeles River flows entirely into the mains, reducing irrigation deliveries by 95%. The last sale of zanja water occurred on May 15, 1904—a symbolic moment, as it was also the year Mulholland began surveying routes for the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Click HERE to see more in Zanja Madre (Original LA Aqueduct) |

* * * * * |

Early Water Pipes and the Move Underground

As open ditches declined, Los Angeles turned toward underground pipes to deliver water more efficiently. Early wooden pipes marked the city’s first buried water system. Though primitive and short-lived, they laid the groundwork for modern water infrastructure. |

| Hollowed Logs | Wood Pipes w/Metal Cable | Wood Pipes and Metal Connections |

Historical Notes In the earliest days of Los Angeles' water distribution system, wooden pipes—typically hollowed-out logs bound with metal cables—served as the city’s first underground plumbing network. These primitive conduits carried water from the open-air zanjas (irrigation ditches) to homes, businesses, and other early infrastructure. At critical junctions and control points, iron couplings were used to join sections or install valves, offering a modest step toward durability and pressure management. Most of these wooden mains were just three or four inches in diameter and prone to leakage, rot, and bursting under strain. As the city grew and demand for water increased, iron pipes eventually replaced their wooden predecessors—marking a key transition from a frontier system to a more engineered municipal network. |

|

|

| (2025) – Photo showing a wooden pipe used to supply water to a building in the Los Angeles Plaza area, likely dating to the late 1800s. Photo courtesy of Bonnie Kirkland, taken by her grandfather, Ray Korber, for the Los Angeles Water Department in the early 1900s. |

Historical Notes In early Los Angeles, as reliance on open ditches like the Zanja Madre proved limiting for a growing population, the city adopted hollowed-out logs as its first underground water conduits. These logs—usually made from redwood or other durable timber—were drilled or burned through to create a bore and then laid end-to-end, sometimes reinforced with metal cables for strength. The system allowed water from the zanjas to be delivered more directly to adobe homes and businesses near the Plaza. Though rudimentary, it marked the city’s first step toward a piped water supply. Leaks, rot, and the small three- to four-inch diameter limited their long-term viability, but the concept of buried pipes was now in place. |

|

|

| (2025) – Cross-sectional view of a wooden water pipe once used in early Los Angeles. This photo was provided by Bonnie Kirkland and originally taken by her grandfather, Ray Korber, for the Los Angeles Water Department in the early 1900s. |

Historical Notes To improve capacity and performance, Los Angeles later introduced stave-and-banded wooden pipes, constructed similarly to wooden barrels. Narrow wooden staves were bound together by metal hoops or bands, forming cylinders that could carry water under modest pressure. These pipes offered longer runs and a tighter seal than hollowed logs, reducing water loss and supporting broader urban distribution. Iron couplings were used at junctions and valve points, blending wood and metal in a practical hybrid. Though still susceptible to decay and bursting, these pipes represented a significant upgrade and were commonly used into the late 1800s. |

|

|

| (2025) – Side view of a wooden water pipe used in the early Los Angeles water distribution system. These hand-carved pipes—typically made from redwood or pine—were commonly used in the late 19th and early 20th centuries before being replaced by more durable iron and steel infrastructure. Photo courtesy of Bonnie Kirkland, taken by her grandfather, Ray Korber, for the Los Angeles Water Department in the early 1900s. |

Historical Notes Another form of wooden piping used near the Plaza area included box flumes—essentially wooden troughs built from flat planks and either buried or left exposed depending on terrain. These were used not just for conveyance over distance but also to bridge elevation changes or cross streets. While they lacked the pressure tolerance of cylindrical pipes, box flumes were easy to construct and maintain, especially for temporary or seasonal use. As the city's water demand increased, these wooden systems—like the flumes and stave pipes—were gradually replaced by cast iron mains starting in the late 19th century, ushering in a new era of municipal infrastructure. Click HERE to see more in LA's Early Water Works System Click HERE to read more in Pueblo to Metropolis - A Short History of LA Water |

* * * * * |

History of Water and Electricity in Los Angeles

More Historical Early Views

Newest Additions

Early LA Buildings and City Views

* * * * * |

Recommended Reading:

See The Zanjas and the Pioneer Water Systems for Los Angeles by Abraham Hoffman and Teena Stern. Southern California Quarterly 89 (Spring 2007)

References

DWP Publication: 'The City Owns Its Water'

Annual Report of the Bureau of the Los Angeles Aqueduct to the Board of Public Works, 1907

Water and Power: The Conflict Over Los Angeles Water Supply...William L. Kahrl

Los Angeles Herald, February 14, 1902 Article: Water Board is Fully Organized

Los Angeles Express, August 4, 1905 Article: Fred Eaton Back from Owens River

Los Angeles Times, July 29, 1905 Article: Titanic Project to Give City a River

The Influence of the Los Angeles “Oligarchy” on the Governance of the Municipal Water Department

http://scripophily.net/deofwaandpoo.html

* DWP - LA Public Library Image Archive

*#Noirish Los Angeles - forum.skyscraperpage.com

++LA Public Library Image Archive: Drawing by Orpha Klinker Carpent

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Major Efforts

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Board Officers and Directors

- Mulholland/McCarthy Service Awards

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index