Tunnel Construction on the LA Aqueduct

|

|

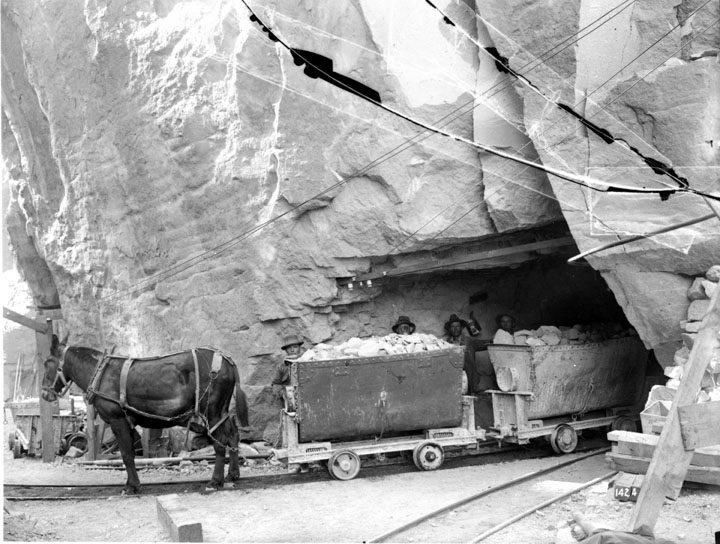

| Tunnel construction - 142 tunnels were dug totaling forty-three miles in length. Elizabeth Tunnel was the longest with a length of over five miles. |

|

|

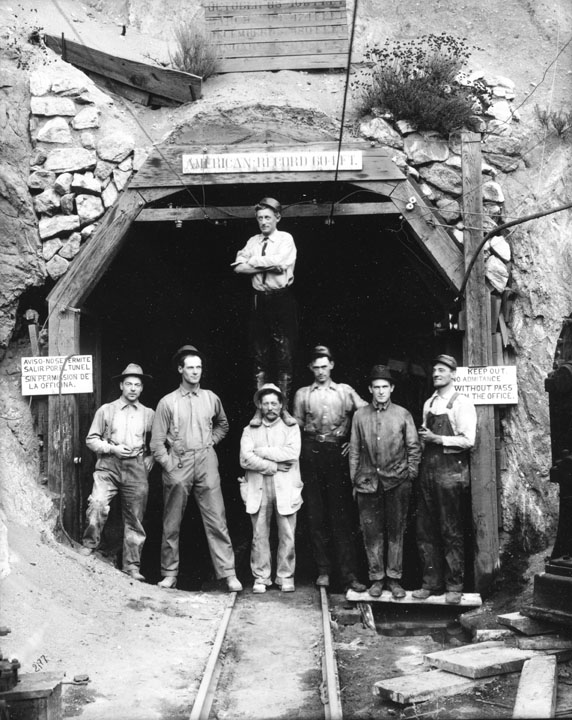

| (1908)* - Construction crew at the north portal of Elizabeth Tunnel. |

Historical Background

The Los Angeles Aqueduct crosses under the crest of the Coast Range 45 miles north of the City of Los Angeles. The Elizabeth Lake is approximately one-half mile east of the center of the tunnel, and a number of small lakes are situated in the valley westerly from Elizabeth Lake. The tunnel is 26,870 feet long, or 5.09 miles. The coast range has a double crest at this point, with the valley of the Elizabeth Lake almost in the center of the tunnel line. Where the tunnel crosses this valley, it is 250 feet beneath the surface of the ground.

Work was started by hand at the South Portal on October 5, 1907, and at the North Portal on November 1, 1907, and was so prosecuted until adequate machinery could be installed. It was supposed that this long tunnel would be the controlling factor in the time necessary for the completion of the Aqueduct. Consequently, equipment of a substantial character was placed here, consisting of four 500 cubic feet per minute two stage air compressors, which was a duplicate air installation at both the north and south ends. One 18-inch Positive Blower and a track of 36-lb rails on which electric locomotives were operated were furnished for each portal.

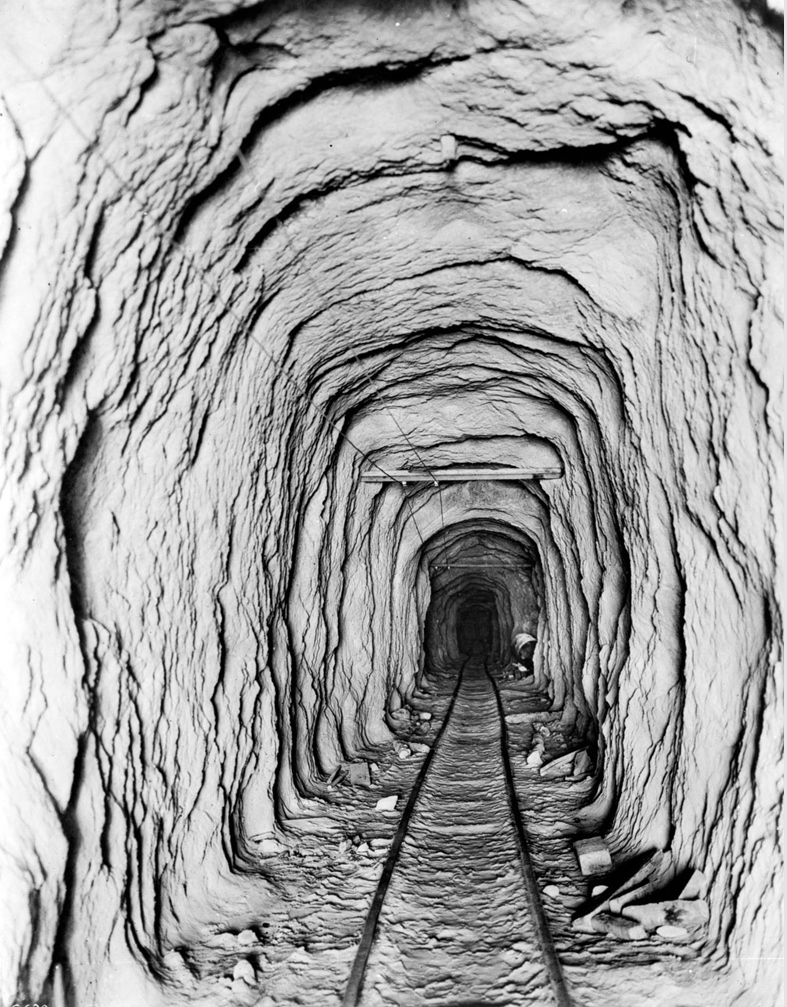

The tunnel was driven on a slope of one foot in a thousand. The timbered section required a theoretical excavation of 5.02 yards per lineal foot, and the un-timbered section 4.18 yards. This is to be a pressure tunnel and is the outlet from the bottom of the Fairmont Reservoir. It will be a portion of the penstock of the first power plant south from the crest of the range. The amount of water discharged through the tunnel will vary with the load on the power plants up to 1,000 cubic feet per second and average 400 cubic feet per second for the day. The fact that the tunnel diverts from the Fairmont Reservoir will permit of this fluctuation. As the electric load factor in Los Angeles is estimated at 40 per cent, the maximum flow of water from the tunnel is two and one-half times the mean. The hydraulic gradient, therefore, will vary with the volume discharge, and will be cared for by the depth of 80 feet of water over the intake of the tunnel.

The formation at the north half of the tunnel was very much broken and consisted mostly of decomposed granite. Much of the ground was very heavy, requiring close timbering, and in numerous places the tunnel had to be re-timbered two or three times. Large flows of water were encountered and also swelling ground. The excavation of this portion of the tunnel was most difficult, and called for courage, skill and persistence. At 1,117 feet from the North Portal, large fissure filled with sand and water was encountered which broke through the face of the tunnel and could not be passed from that side. This caused considerable delay. Therefore, a shaft was put down 3,000 feet from the portal, and the heading driven each way there from, in order to maintain the progress schedule and to approach the dangerous ground more guardedly from the south. This running water and sand was finally overcome by driving overlapping steel rails in advance of the heading, and closely following with careful excavation and timbering. Mr. John Gray, superintendent for the north end, has accomplished a remarkable work in the driving of this half of the tunnel without further mishap.

The south half of the tunnel was in gneissoid granite, in some places rather soft and in others, hard. Broadly speaking, it was ideal tunnel ground. This portion of the tunnel, as a rule, required no timbering. The south end was in charge of Mr. W. C. Aston, tunnel superintendent.

In driving the tunnel in hard rock, the full section was drilled and shot, each shift getting in a round and firing it. Where the ground was heavy at the north end, a lower heading was driven in advance, using false sets and crown bars which carried the weight of the roof ahead of the front set. The tunnel was then widened by putting in the permanent posts, the temporary floor from which the upper section of the tunnel was excavated and mucked resting on them, the roof segments being placed as the excavated material was removed, the whole process being one of the carefully detailed advance.

The lining of the tunnel was started in May, 1911. The plan has been adopted of beginning at the center rand carrying the lining towards both the north and south portals at the same time. Rock crushing and mixing plants have been erected at both portals, and the lining of the tunnel has been placed in charge of Mr. W. F. Webb, construction superintendent. In the portions of the tunnel where the ground is very heavy, it is proposed to replace the timbers with steel “I” beams, which will be concreted into position, and lend additional strength to the lining.

The excavation of the Elizabeth Tunnel has been done by the Engineering Department by day labor.^

|

|

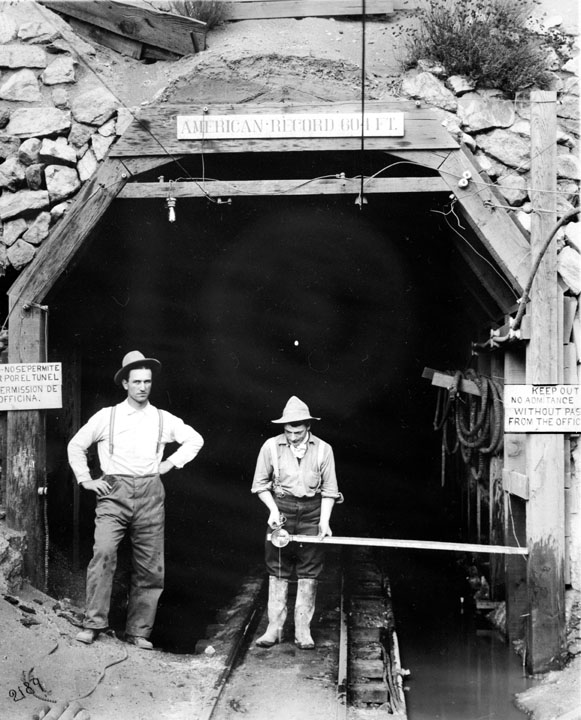

| (1908)* - Construction crew in front of the south portal of the Elizabeth Tunnel. The construction of the Elizabeth Tunnel took four years and seven months and was completed on February 29, 1911, 450 days under the estimated time. |

|

|

| (ca. 1908)* - Workers pose at the portal of the Elizabeth Tunnel, just north of the San Fernando Valley, where workers set a record for hard-rock drilling |

From the LADWP Historic Archive

At midnight, Sunday, February 26, 1911, about 25 feet of granite separated the north and south portal tunnel crews form joining the five-mile-long Elizabeth Lake Tunnel, south of Fairmont Reservoir, on the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

This tunnel, the longest on the Aqueduct and second in the U.S to the 30,000 foot Gunnison Tunnel in Colorado, was the key in Mulholland’s construction timetable. Regardless of the progress of other Aqueduct divisions, “The Chief” knew that Owens River water would not flow into Los Angeles until the Elizabeth Tunnel was driven to completion.

John Gray, the hardrock tunnel expert who was engaged in the preparatory Aqueduct work in the northern divisions, came south to open both portals; south, September 20, 1907, and north, November 1, 1907. In May 1908, mining engineer W. C. Aston took charge of south portal operations from engineer McLeod who had bossed the driving since January 1908. Gray devoted his energies to driving the difficult north portal.

ROUGH BEGINNINGS – Progress during the first few months was slow due to natural disorganization and a tight money situation which resulted in the use of some less efficient, “secondhand” equipment and less experienced men.

By June 30, 1908, the south heading had been driven 1,230 feet, to the north’s 993 feet. The situation improved from this time on due to the availability of Aqueduct bond monies. New equipment was purchased and a bonus system was put into effect which increased the average miner’s wages by 30 per cent. These wages were handsome enough to lure the cream of hardrock miners to Elizabeth Tunnel.

Now working with the best equipment and manpower available, both headings were pushed forward at an unexpected 22 feet-a-day average, or six feet more than the estimate. The south heading had extended 5,341 feet while the north measured 4,888 feet on June 1, 1909.

RECORDS BROKEN – At the south portal, the American record for hardrock tunnel driving in a single month was broken on three occasions. The last being 604 feet driven during April 1910.

By June 30, 1910, the north crew had captured the lead 10,821 to 10,798 feet. This feat was all the more impressive considering the many days lost due to flooding and slides in the north. This portal, which crossed the San Andreas Fault, was “wet and loose,” requiring extensive timbering for nearly its entire length. Water was a constant headache because the north heading always angled downgrade. But, by pumping 350 gallons per minute from the heading the miners had only to contend with knee-deep water.

In late 1910, the south again took the lead when the north’s heading roof began pouring down water. Superintendent Gray joined his miners in waist-deep water for 48 hours helping to timber and pump, but it took 10 days before the tunnel was dried out to the normal 20-inch depth to enable “shooting” and drilling to continue.

CLOSING THE GAP – Tensions at both headings had built during February 1911, when the first sounds of the rival crew’s “shots” from beyond the granite were heard. During the last week a new sound of steadily increasing volume was heard between “shots.” This was the pencil-tapping-on-a-table staccato of the big Leyner compressed air drills. These drills, the most modern, were capable of driving a 1 ½ inch bit through 24 feet of granite. They were also quite capable of drilling into a stick of dynamite placed by the other crew preparing to “shoot,” causing a disastrous premature “shot.”

But by February 26, time seemingly was running out for Gray’s north portal crew. The south had bored beyond the halfway point and was now at the 13,478 foot mark. If Gray’s crew was to hole through first, it would need some strong action and a bit of luck.

The strong action was decided to be in the form of quick “shot” that Gray felt would breach the granite, bringing victory to the north portal. He gave instructions to Culbert Fountain, the portal foreman, to prepare to shoot the next morning. Twenty-five feet to the south, Aston’s plan was to drill through in one place rather than blast down the entire wall.

DRILL VS. DYNAMITE – Shortly after 10 am Monday, Aston’s foreman Rodney Carwithen planted himself facing the wall and “set” the clattering Leyner air drill into the granite. Minutes passed – 10 – 20 – 40, but Carwithen stopped only to change bits.

By 11 am, Fountain reported the Gray that he was ready to “shoot.” Fifteen holes had been drilled in the rock face. Sixty sticks of dynamite were brought up on the run by the powder boy and two mockers – their arms full. Four sticks were tamped into each hole by the miners and the electrician began his work. The rest of the men sloushed back up the tunnel 500 feet to the telephone station.

Gray was already on the phone talking to Barney Powers, a foreman in the south tunnel.

“Barney, get your men out of that tunnel in a hurry; we’re ready to “shoot!”

“Give us fifteen minutes and let ‘er go,” Powers replied.

Carwithen was still at the Leyner when work came to evacuate. He had drilled 21 feet, 6 inches.

At 11:15 am, Gray, Fountain and the others at the telephone station felt the violent quest of wind that nearly tore the hats from their heads. The wind was followed by the crashing roar of the first charge, followed by the second.

“Hasn’t broken through yet,” said Gray.

A careful count was kept as the remaining charges were ignited; the miners disliked hitting an unexploded charge hidden in the muck with a pick head.

MINE GAS PUMPED – After the 15 reports had been noted, Fountain had an air pump set up to suck off the head of gas that had formed in the blast area. This took about 10 minutes then the men waded back to the new heading.

Candles were lit and knee deep in water, Fountain began inspecting the heading wall. As one of the candles was being moved along the wall its flame fluttered for a moment then inclined south. A draft! The tunnel was connected!

At 11:26 am, Fountain scrambled to the top of a granite boulder and sweeping aside a bit of wet sand revealed a 1 ½-hole in the wall. He cupped his hands, around the hole, placed his lips to his hands and shouted. “HEY!”

Silence descended on both tunnels. Not a sound or stirring – then a hollow but clear “HELLO” rang out from the other end of the hole.

Simultaneous cheers bounced off the sweating granite walls 350 feet below Elizabeth Lake Valley as the miners gathered at either end of the hole. “Who is it? Who is it?” Fountain bawled into the hole. “It’s me –Barney,” came the reply now strong and distinct.

“We beat you to it,” shouted Fountain.

“That is our hole,” called Powers, “the south portal wins.”

“Yes, that’s your hole, but we broke into it and we win,” replied Fountain.

Who really won? No question about it – the winners were the people of Los Angeles.

After 1,215 days of toil and at two-thirds the estimated cost and in two-thirds the time allotted by the Board of Consulting Engineers, the remarkable Elizabeth Tunnel, 26,870 feet long, was initially joined. The amount of error was remarkable too for the opposing shafts were off center 1 1/8 inches while the grade checked within 5/8 inch.^

|

|

| (ca. 1908)* - The Elizabeth Tunnel set the world record for hard rock tunnel driving: 604 feet in one month. |

|

|

| (ca. 1908)* - View of a tunnel opening showing a mule pulling rail cars full of rocks. |

|

|

| (1913)*^ - Photo of a tunnel in the Owens River Gorge. Two rail tracks run along the bottom of a craggy tunnel, the ceiling of which has beams to which wires are attached. |

|

|

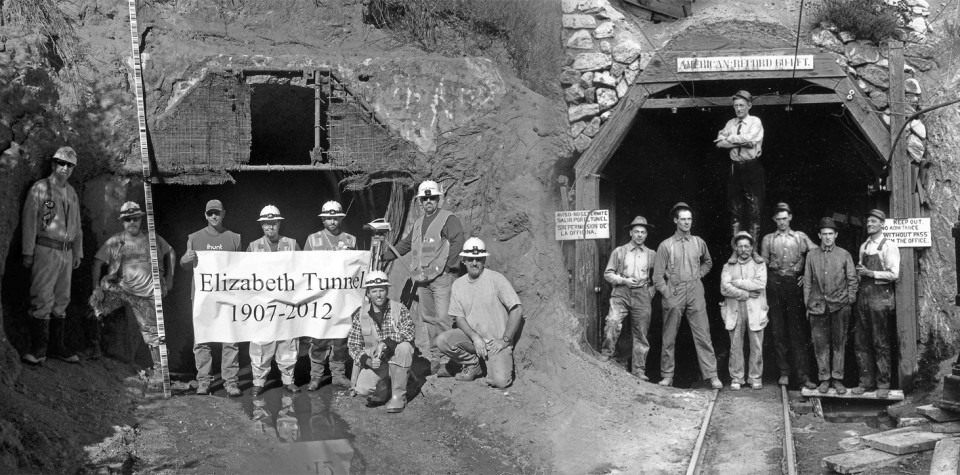

| (2012)^* - Side-by-side view showing two groups of workers posing in front of the Elizabeth Tunnel 115 years apart. |

References and Credits

* DWP - LA Public Library Image Archive

^*LADWP: LA Aqueduct Centennial 2013

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Mulholland Service Award

- Major Efforts

- Board Officers and Directors

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index