The Story of the Los Angeles Aqueduct

Introduction |

The Los Angeles Aqueduct is one of the most important public works projects in the city’s history. Completed in 1913, it brought water from the Owens Valley to a rapidly growing Los Angeles and made large scale urban expansion possible.The aqueduct is also one of the most debated projects in California history. It stands as a major engineering achievement, but it also triggered long lasting conflict, environmental change, and deep resentment in Owens Valley. The images and notes in this section trace both sides of that story. |

|

|

| (1912)* - Owens River in the Owens Valley, showing a lone fisherman along its banks. |

| Historical Notes

The Owens River flows through a dry valley east of the Sierra Nevada and once carried enough water to sustain farms, ranches, and Owens Lake at the south end of the valley. For generations, the river supported a small but stable agricultural economy in an otherwise arid region. By the early 1900s, Los Angeles was searching for a new water supply to support rapid growth. The Owens River, distant and seemingly abundant, became the focus of plans that would permanently change both the valley and the city. |

|

|

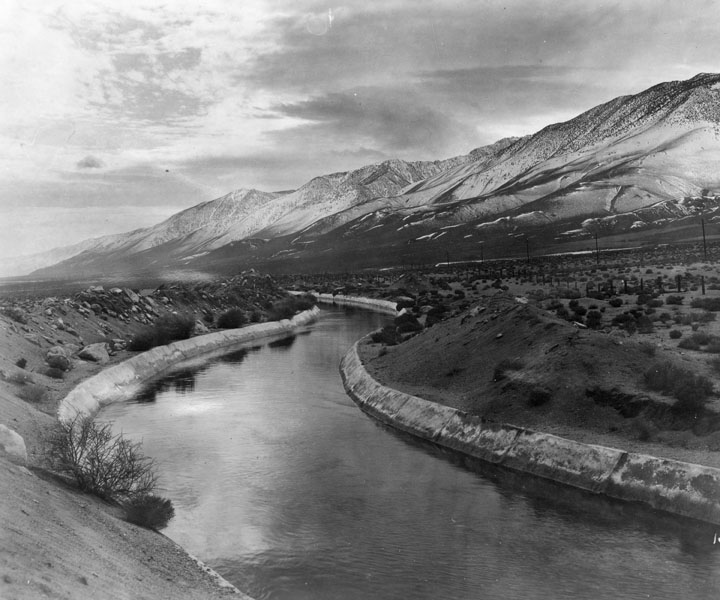

| (1928)* - Los Angeles Aqueduct in the Owens Valley near Alabama Hills, November 24, 1928. |

| Historical Notes

This panoramic view shows the aqueduct settled into the Owens Valley landscape fifteen years after water first reached Los Angeles. What began as a massive construction effort had become a permanent part of the valley’s geography. The aqueduct followed the natural contours of the land, relying on careful surveying and gravity flow rather than pumps. Its visibility across the valley made it both a symbol of engineering achievement and a reminder of water leaving the region. |

|

|

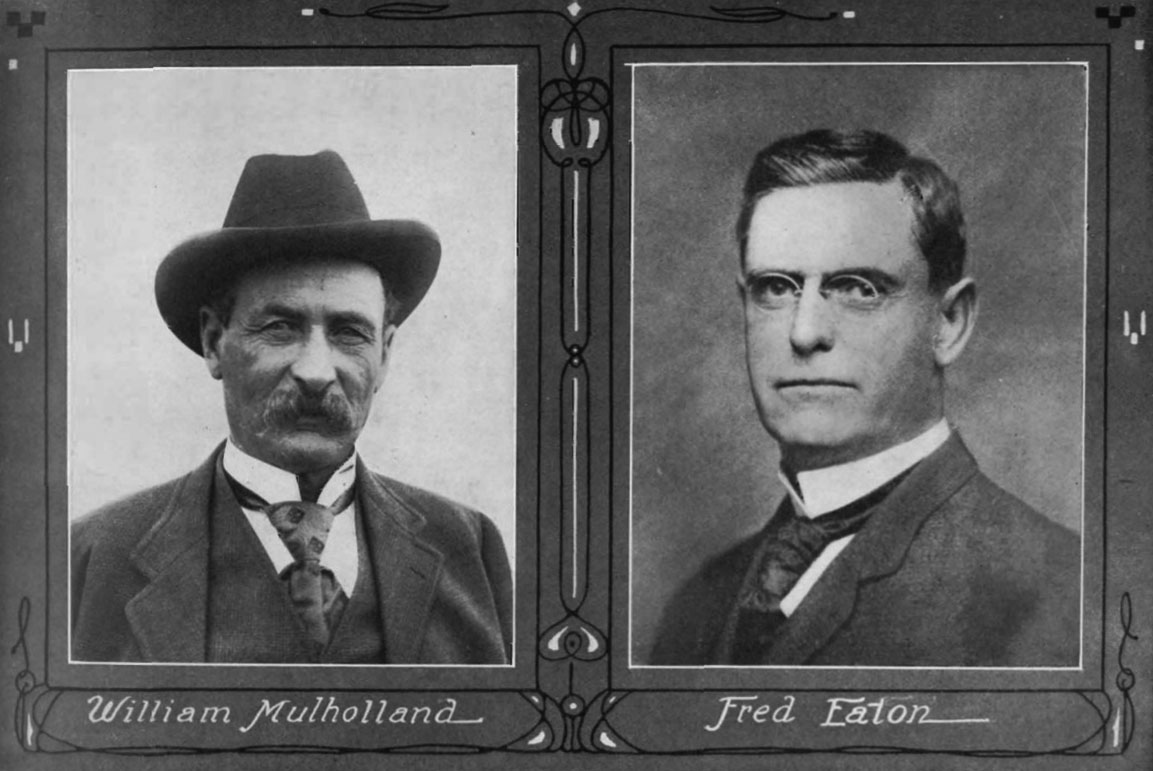

| (1913)* – Portrait photographs of William Mulholland and Fred Eaton |

| Historical Notes

William Mulholland was the chief engineer of the Los Angeles water system and the driving force behind the aqueduct’s design and construction. Largely self educated, he rose from ditch tender to one of the most influential water engineers in the American West. Fred Eaton, a former mayor of Los Angeles, played a key role in identifying Owens Valley as a water source and acquiring land and water rights. Together, their actions helped launch a project that reshaped Southern California and ignited lasting controversy. |

|

|

| (ca. 1907)^*– William Mulholland and companions in the Owens Valley, surveying the future aqueduct route. |

| Historical Notes

In 1905, Mulholland formally recommended the Owens River as the best available long term water supply for Los Angeles. The city soon applied for access across federal lands, an essential step since much of the route crossed public territory. The scale of the plan was unprecedented for Los Angeles. The aqueduct would stretch hundreds of miles and rely almost entirely on gravity to move water from the Sierra Nevada to the city. |

|

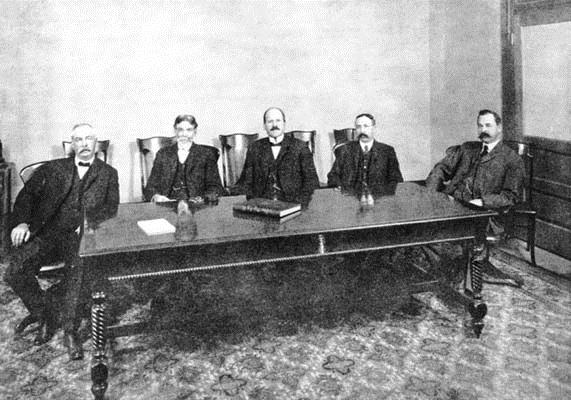

| The Board of Water Commissioners of the LA Department of Water and Power at the time of the building of the LA Aqueduct to Owens Valley. (L-R) John J. Fay, J. M. Elliott, Moses H. Sherman, William Mead, and Fred L. Baker. |

| Historical Notes

The Board of Water Commissioners oversaw the legal, financial, and administrative decisions behind the aqueduct. Their approval was required for land purchases, contracts, and overall direction of the project. Some board members were also involved in land development, especially in the San Fernando Valley where aqueduct water would emerge. This overlap later fueled accusations of insider advantage and remains part of the debate surrounding the aqueduct’s history. |

|

|

| (ca. 1911)* - Owens Valley during the planning and construction period of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. In this view, the aqueduct skirts around Owens Lake, a closed basin lake with no outlet to the ocean. |

| Historical Notes

By 1907, Los Angeles had secured major financing for the project and began pursuing the permissions needed to build across large stretches of federal land. The aqueduct could not be built without access through public territory, and this required approval at the national level as well as careful legal planning. This view also points to an important part of the story that unfolded over time. Owens Lake is a closed basin lake with no outlet to the ocean. As aqueduct diversions increased after 1913, much less water reached the lake. Over the following years the lake level fell dramatically, becoming one of the most visible and debated environmental changes linked to the aqueduct era. |

* * * * * |

Construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct

Once funding and approvals were in place, construction became a race against distance, terrain, and time. The route crossed deserts, mountains, and wide open basins, requiring new roads, work camps, supply lines, and constant surveying to keep the gravity flow design on grade. |

|

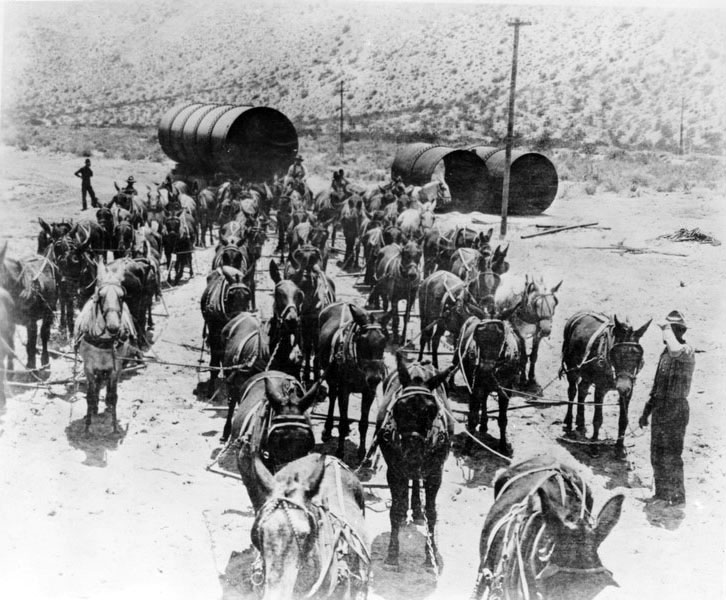

| (1912)* - Transportation was largely by mule power when the Los Angeles Aqueduct was under construction. This photo shows a 52-mule team hauling sections of aqueduct pipe. Work on the aqueduct was started on September 20, 1907. |

| Historical Notes

Much of the aqueduct was built in remote areas with little existing infrastructure. Heavy pipe, cement, tools, and supplies were hauled by mule teams across deserts and rough terrain. The image highlights the physical challenge of the project. Construction depended not only on engineering skill, but also on enormous human and animal labor under harsh conditions. |

|

|

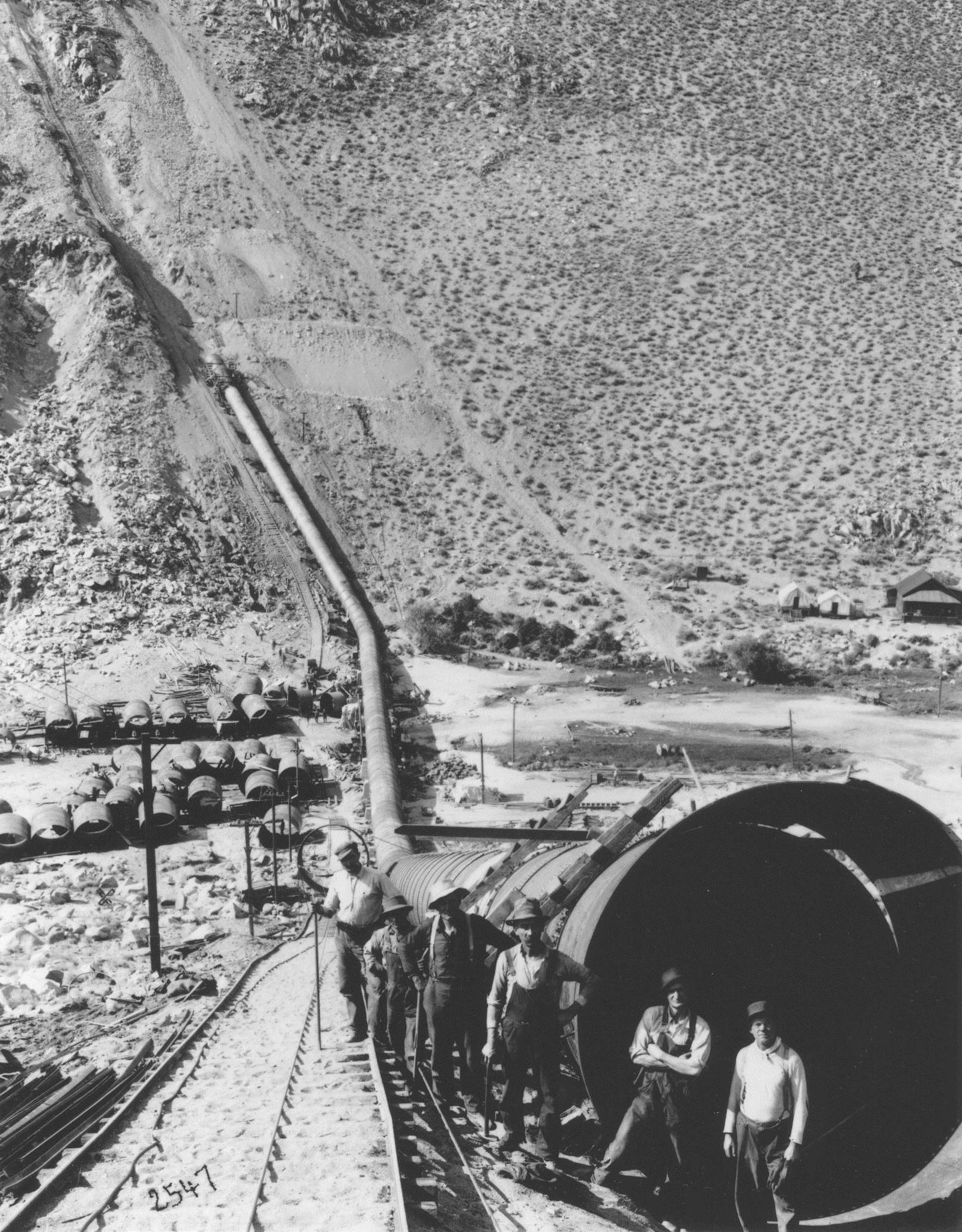

| (ca. 1912)* - Aqueduct workers posing beside a newly completed section of pipeline. |

| Historical Notes

Thousands of workers were employed during construction, drawn by steady wages and the promise of long term work. Camps, supply depots, and support systems were built along the route to sustain the workforce. The job was dangerous and demanding, involving tunneling, concrete work, and exposure to extreme heat and cold. Despite this, the aqueduct was completed ahead of schedule. |

|

|

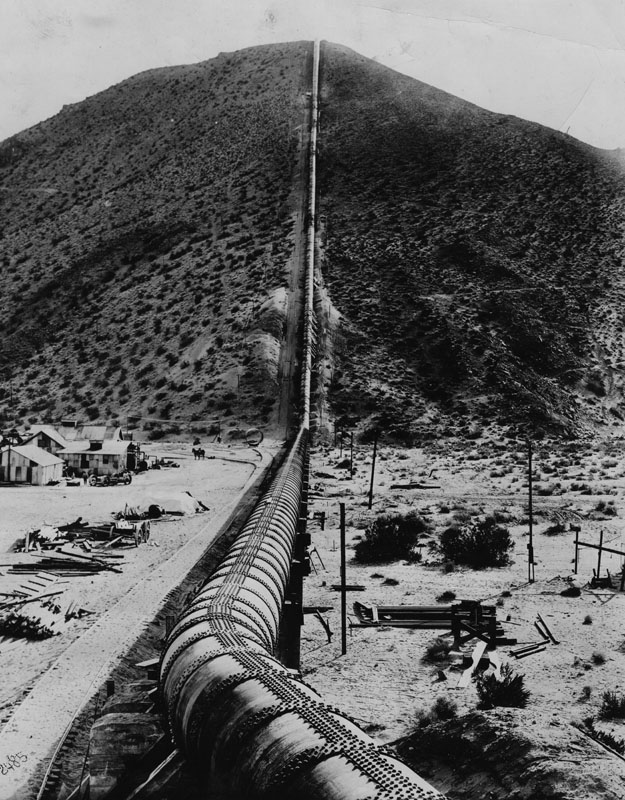

| (ca. 1912)* - Caption reads: The famous Jawbone siphon of the Los Angeles Owens River aqueduct, built by William Mulholland, which crosses two mountain ranges and the Mojave Desert to bring the city its water supply from the snow-capped High Sierras--a 250-mile journey. |

| Historical Notes

Where the aqueduct crossed deep canyons, engineers used inverted siphons that dropped water down and forced it back up using pressure. These structures allowed the system to maintain gravity flow across uneven landscapes. The siphons were among the most technically complex parts of the aqueduct. They remain one of the reasons the project was considered a major engineering achievement of its time. Click HERE to see more on the Construction of the LA Aqueduct. |

* * * * * |

Opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct

The completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct marked a defining moment in the city’s history. After more than six years of construction, the project moved from engineering challenge to public celebration. |

|

|

| (November 5, 1913)* - Official Opening of the water gates of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. |

| Historical Notes

The official opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct took place on November 5, 1913 at the Cascades in the San Fernando Valley. Tens of thousands of people traveled by train, streetcar, wagon, and automobile to witness the event. It was one of the largest public gatherings Southern California had seen at the time and was treated as a major civic milestone. William Mulholland addressed the crowd briefly before water was released into the Cascades. His short statement marked the completion of a project that took more than six years to build. When the gates opened, Owens River water began flowing south by gravity, signaling a new era for Los Angeles. In the years immediately following the opening, the aqueduct allowed Los Angeles to grow at a pace that would not have been possible with local water supplies alone. Neighborhoods expanded, agriculture increased in the San Fernando Valley, and the city’s population rose rapidly. At the same time, the opening marked a turning point for Owens Valley, where the effects of water diversion would become increasingly visible and controversial. |

|

|

| (November 5, 1913)* - Crowds watch as the water gates are opened and the Los Angeles Aqueduct water starts to flow down into the San Fernando Valley. William Mulholland, builder of the aqueduct and H. A. Van Norman, Chief Engineer and General Manager, Water Bureau. |

| Historical Notes

Click HERE to see more on the Opening of the LA Aqueduct. |

* * * * * |

The Aftermath in Owens Valley

The opening of the aqueduct did not bring closure to the story. Instead, it marked the beginning of a new and difficult period for Owens Valley, as the long term effects of water diversion became increasingly clear. |

|

|

| (1927)* – The scene at No Name Canyon after a dynamite attack destroyed 400 feet of pipe on May 27, 1927. |

| Historical Notes

After the aqueduct opened, the relationship between Los Angeles and Owens Valley grew more tense. As the city purchased more land and increased exports of water, many valley residents felt their local economy and way of life were being steadily weakened. The conflict was not only about water, but also about trust, power, and who controlled the valley’s future. By the 1920s, resistance sometimes turned into direct action. There were protests, forced releases at aqueduct facilities, and repeated acts of sabotage, including dynamite attacks like the one shown here. These events did not end the aqueduct, but they became lasting symbols of the anger and loss that many people in the valley associated with the project. |

* * * * * |

Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles - A Complex Relationship

The Los Angeles Aqueduct brought clear benefits to the city, providing a stable water supply that supported growth, industry, and development. Without it, modern Los Angeles would likely look very different.

At the same time, Owens Valley experienced lasting environmental and economic disruption. The aqueduct’s legacy remains contested because it represents progress for one region and loss for another.

Another Perspective

“…the businesses and the homes were leased or rented back to the same people (residents of Owens Valley) to pursue their same activity. Most of them did and very successfully. Because, by that time, the impact of the city's improvements in the Owens Valley, and I don't mean the aqueduct, I mean in connection with the construction of the aqueduct, the city built a broad-gauge railroad from Mojave to Long Pine to connect with the narrow gauge railroad. So for the first time the Owens Valley had rail service to ship any products it had, including ranch products out of the city to Los Angeles. The City used its influence with the State of California to have the highway paved from Mojave to the Owens Valley, and that was done. So access to the Owens Valley because of the City's work, in its own behalf obviously, but still it was there and available to anybody that wanted to use it, both the railroad and the highway. The city built power plants in connection with the construction of the aqueduct, and those plants for a long time provided power to the Owens Valley, which didn't have it before the city came in there with the aqueduct construction.

So there were a lot of benefits that occurred that, in my readings and listening to too many people that have no idea that those things happened or don't wish to... admit that those things happened.”

Robert V. Phillips,

Chief Engineer and General Manager of DWP, 1972-75 (Both Mr. Phillips and his father knew and worked with Mulholland and Van Norman).

Read more of an Insightful Interview with Robert V. Phillips:

Los Angeles Aqueduct History and Photos |

Recommended reading about William Mulholland and the history of water in Los Angeles:

William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles

By Catherine Mulholland

The Water Seekers

By Remi Nadeau

Vision or Villainy

By Abraham Hoffman

Beyond Chinatown

By Steven Erie

Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water

By Marc Reisner

References and Credits

* DWP - LA Public Library Image Archive

^ DWP - The Story of the Los Angeles Aqueduct

^*L.A. Aqueduct Centennial 2013

^# Claremont Colleges Digital Library

*^Wikipedia: California Water Wars; Owens River

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Major Efforts

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Board Officers and Directors

- Mulholland/McCarthy Service Awards

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index